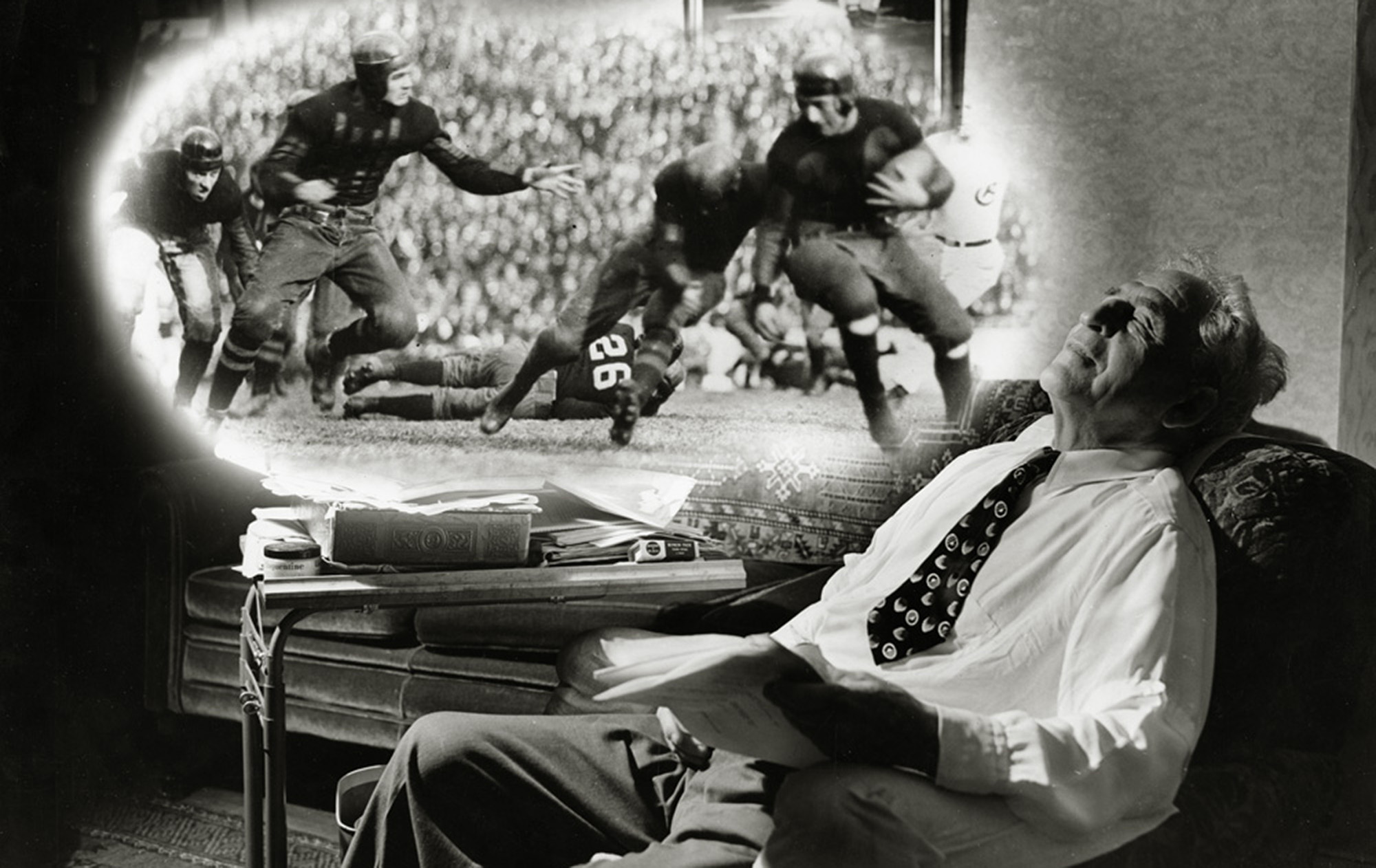

Old Man Stagg and his splendid dream. (UChicago Photographic Archive, apf1-07874r, Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library)

Think you know all there is to know about Amos Alonzo Stagg? A new biography might surprise you.

There is no shortage of books on legendary UChicago athletics director Amos Alonzo Stagg (1862–1965)—starting with a 1927 autobiography that earned a favorable review in the New York Times from Bertrand Russell. But with Amos Alonzo Stagg: College Football’s Greatest Pioneer (McFarland, 2021), David E. Sumner, former head of the magazine journalism program at Ball State University, has written one for the Stagg completist. You might know that Stagg invented the huddle, numbers on jerseys, and the Statue of Liberty play. Here are a few things you might not.

Stagg, Harper, and Hebrew

Stagg turned down offers from six professional baseball teams to study for the ministry at Yale’s divinity school. Many of his classes were with William Rainey Harper, who taught biblical literature and Hebrew. Stagg detested Hebrew—“the deadest and most uninteresting language which developed out of the tower of Babel”—but found Harper an inspirational teacher. Stagg struggled with public speaking and realized he would never make a good preacher. Instead, he became the first baseball and football coach at the International Young Men’s Christian Association Training School. Soon afterward Harper offered Stagg the job as UChicago athletics director.

Brawn food

In A Scientific and Practical Treatise on American Football for Schools and Colleges (Press of the Case, Lockwood & Brainard Company, 1893), Stagg included a long list of banned food and drink: “Pies, cakes, salads, all forms of pork, veal, rich dressing, fried food, ice-cream, confectionery, soda water, so called soft drinks (and it is needless to say drinks of a stronger nature), tea, coffee, and chocolate should be cheerfully and absolutely given up.” Drinking water during football games was “exceedingly bad and never should be permitted.”

A family of coaches

Both of Stagg’s sons, Amos Alonzo Stagg Jr., SB 1923, AM’25, and Paul Stagg, LAB’28, SB’32, played quarterback for UChicago, served as assistant coaches at the University, and later became head coaches elsewhere. Beginning in the late 1930s, after the children were grown, Stagg’s wife, Stella, became his unofficial assistant coach. She charted plays, kept stats, and scouted the opposition—in addition to mending the team’s uniforms. Once a player asked why she had been sitting on the sidelines taking careful notes all week. “Young man,” she told him, “I’m just deciding whether you start Saturday or not.”

Strong opinions

Stagg opposed fraternities, which he considered elitist. He disapproved of professional athletics; he considered professional football “purely a parasitical growth on intercollegiate football.” He once nailed a poster on the door of Bartlett Gymnasium, informing students of a standard uniform (costing $4) for their required gym classes. Students responded by nicknaming him “Luther.”

Young at heart

Stagg retired at age 98, after coaching for 70 years. That year one of his birthday presents was a power mower. Stagg sent it back. He preferred to use a push mower to keep in condition. When Stagg died in 1965 at age 102, he was the last surviving member of UChicago’s original 1892 faculty.