Patrons, staff, and friends of the fabled neighborhood bar tell its story.

When is a bar more than a bar?

Jimmy’s Woodlawn Tap turned 75 this year. During its lifespan it has had only three owners: Jimmy Wilson, brothers Bill and Jim Callahan, and Matt Martell, AB’95, who bought it in 2021. And little else has changed much: the decor, the amount of sunlight filtering through the windows facing 55th Street season to season, the cost of a hamburger, the clientele. In a neighborhood that has seen significant change, Jimmy’s is a remarkably stable presence. Some of that is intentional—for instance, Jimmy’s continues to open every morning before lunchtime, unlike many bars—but outside forces have steadied it as well.

Jimmy’s serves a larger function in the community. It’s not just a place to blow off steam, meet friends, and escape the pressures of school or work, but a place to celebrate the values of Hyde Park and the University—which include a certain aversion to hype or grandness. For those lucky enough to be in the know, Jimmy’s has always simply been, as Saul Bellow, EX’39, once explained to an interviewer, “our local haunt ... a joint I had known in earlier times.”

Speakers, in order of appearance

Carole Rich is one of Jimmy Wilson’s daughters.

John Davey, LAB’57, AB’61, JD’62, is on the board of directors at Lakeside Bank.

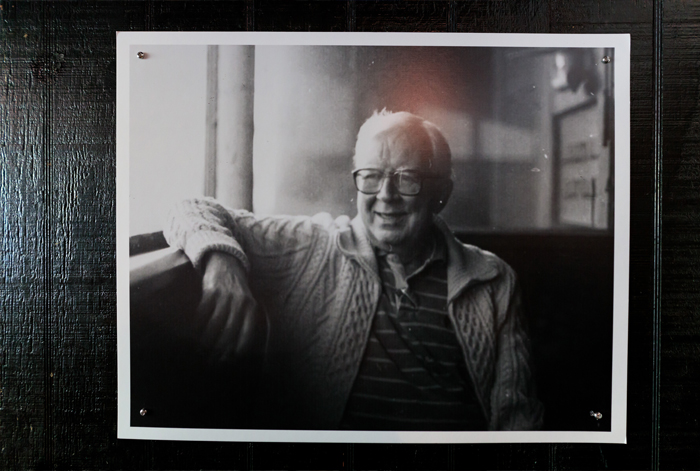

Bill Callahan owned Jimmy’s from 1999 to 2021.

Matt Martell, AB’95, is the current owner of Jimmy’s.

David Axelrod, AB’76, is the former chief strategist and senior advisor to former President Barack Obama and founding director and current senior fellow of UChicago’s Institute of Politics.

David G. Booth, MBA’71, is the founder of Dimensional Fund Advisors and the namesake of the University of Chicago Booth School of Business.

Jack Snapper, AM’69, PhD’74, is associate professor emeritus at the Illinois Institute of Technology.

David Brooks, AB’83, is a columnist for the New York Times.

Sarah Koenig, AB’90, is the executive producer of Serial Productions.

Jack Spicer is preservation chair of the Hyde Park Historical Society.

Vyto Baltrukenas, AB’74, has worked at Jimmy’s since the 1970s.

Hanna Holborn Gray is the Harry Pratt Judson Distinguished Service Professor Emeritus of History and former president of the University.

Stephen Anderson is a retired options and commodities trader.

Janet Coleman is the author of The Compass: The Improvisational Theatre That Revolutionized American Comedy (Knopf, 1990).

Curtis Black, EX’79, is a writer, editor, and musician.

John W. Boyer, AM’69, PhD’75, is the Martin A. Ryerson Distinguished Service Professor of History and senior advisor to the president. He was previously dean of the College.

June Skinner Sawyers is the author of Chicago Beer: A History of Brewing, Public Drinking and the Corner Bar (American Palate, 2022).

Joseph G. Peterson, AB’88, works at the University of Chicago Press. He is the author of nine books of fiction and poetry.

Sudhir Venkatesh, AM’92, PhD’97, is the William B. Ransford Professor of Sociology at Columbia University.

Nina Helstein, LAB’60, AB’64, AM’75, PhD’95, is a clinical social worker.

I

Officially, it was called the Woodlawn Tap, one of at least six neighborhood bars that flourished on or around Fifty-fifth Street. There, particularly, and at Steinway’s Drugstore (“the morning place”), discussion groups or “cadres” formed and specialists in various intellectual obsessions held forth at separate tables. The Kant table, the Hegel table, the quantum physics table, the Communist table, and the science fiction table persist in many student memories. But even those passions were upstaged by that of the theatre table.

—Janet Coleman, The Compass: The Improvisational Theatre That Revolutionized American Comedy

Carole Rich: My father was James Rowan Wilson. He went to Englewood High School and played basketball. High school is as far as he got. He couldn’t be in the service because he couldn’t hear, so when the war started, he went to work at a nut and bolt factory called United Screw, or something like that. And he worked as a teller at Drexel National Bank. At night he would tend bar at a tavern on 55th Street called the University Tap.

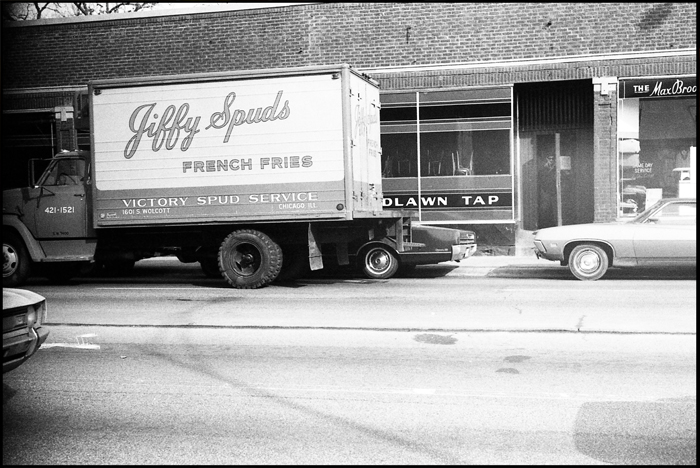

John Davey: Fifty-fifth Street was a line of bars, probably one a block all the way down to Stony Island on both sides.

Carole Rich: My mother lived at 60th off Halsted, and Dad lived at 43rd and Cottage Grove. His dad owned a hardware store that was in business for one hundred years.

Bill Callahan: There were, I think, 35 liquor licenses between Cottage and the lake. And some hotels. It was after the war. Guys were coming back without jobs or anything.

Carole Rich: Dad heard that the tavern down the street had become available. He knew the janitor, the guy who cleaned up. So they went in.

Matt Martell: In the 1940s the bar was called Little Tom’s Place. It became known as Jimmy’s after Jimmy Wilson bought it in 1948.

II

Carole Rich: It was dark, very dark. You needed a match to find your hamburger.

David Axelrod: It was kind of scuzzy. I always felt like my elbows stuck to the tables. I don’t know if they ever changed the oil in which they cooked the fries.

David G. Booth: They served a standard kind of hamburger. You know, a little greasy.

Jack Snapper: The hamburgers were just a pile of grease in a bun.

David Brooks: The floors were sticky. It wasn’t that nice, which was good.

Sarah Koenig: It was disgusting. I loved it.

Jack Snapper: Everybody was worried about falling through the floor and ending up in the basement, particularly when rolling kegs. You had to be very careful where you stepped when carrying a 50-pound barrel of beer.

Carole Rich: It always seemed crowded. And some of the people would be sitting there reading. They had dictionaries and stuff.

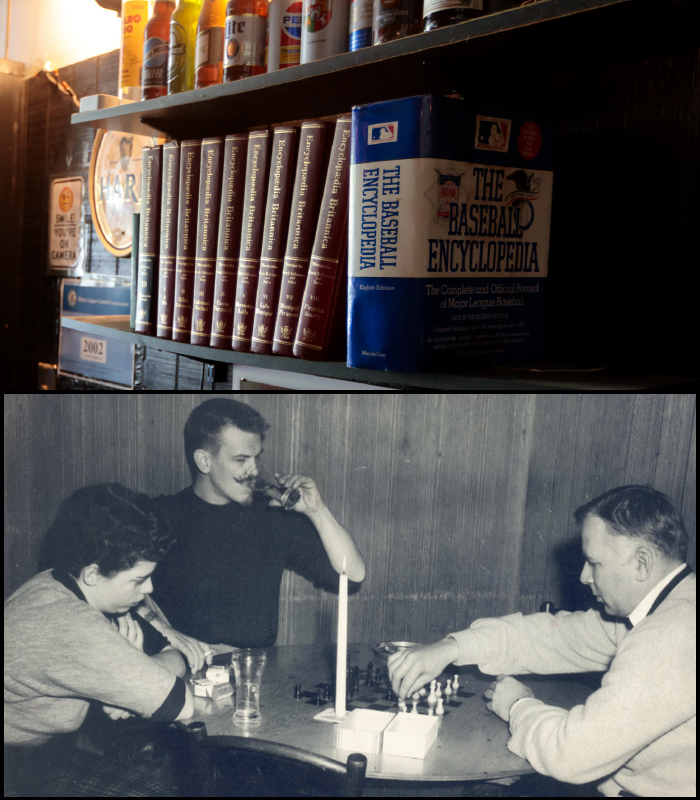

David Brooks: There was an encyclopedia in case you needed to settle a question. And there were long tables where you could get 12 or 16 people together. In retrospect, that was an important piece of the architecture.

Carole Rich: A lot of people met their sweethearts there.

Jack Snapper: There were three different types of clientele. At noon you got blue-collar workers coming in for a light lunch and a beer. Then around four or five the bankers came in, the white-collar people getting off work. The students would hit the place after around nine or ten and then it would really get busy.

Sarah Koenig: It felt like a proper grown-up place, a safe space to practice being an adult. And apparently what adults do is they go to bars, talk a lot, and drink beer.

Jack Spicer: It always had a peculiar culture. All kinds of people felt comfortable there—White, Black, young, old. Not a lot of bars are like that.

Vyto Baltrukenas: When I’d go to other places, I was amazed if they weren’t like Jimmy’s. At Jimmy’s you would pull up and have a conversation with a professor or a plumber. I’d go to other places and, you know, everybody looks the same.

Hanna Holborn Gray: It was kind of a mythical place. There were many people whose days were not complete if they had not paid a visit to Jimmy’s.

Stephen Anderson: People knew the bar as Jimmy’s. But if you said the Woodlawn Tap, they’d say, Do you mean the bar at 55th and Woodlawn?

Vyto Baltrukenas: If you called information and asked for the number, you got some lounge on the North Side. To get 1172 East 55th Street, you had to be in the know.

Hanna Holborn Gray: I was quite empathetic toward it, but I never went there myself.

David G. Booth: Jimmy’s was a place where normal people would have interesting conversations. Normal for University of Chicago students.

Jack Snapper: Somebody called the bar once and asked, “Do you know the source of the line, ‘And malt does more than Milton can to justify God’s ways to man’?” And I said, “Yes, that’s A Shropshire Lad by A. E. Housman. Would you like me to recite it for you?” Apparently I helped someone win a bet.

III

Look at 55th Street. There used to be 35 bars between Lake Park and Cottage on 55th. The street was one of the main places in the city to hear music—making it one of the major centers of music in the nation. Any given night you could hear performers like Charlie Parker, Miles Davis, Muddy Waters, Sonny Stitt in a saxophone duel with Gene Ammons, Coleman Hawkins, Lester Young, Clifford Brown, and on and on.

—Curtis Black, “Condemn and Destroy,” The Grey City Journal, September 24, 1982

Janet Coleman: Robert Maynard Hutchins wasn’t interested in frivolous activities. He wanted people reading the great books. So the students went to the bar—where else would they go? And because people have an urge to perform, especially young people, they started doing improvisational theater.

Carole Rich: When I was 18 I would go there and listen to jazz. It was always a mixed crowd. There was no segregation.

Janet Coleman: The Compass was the first improvisational theater in America. A lot of the Compass Players hung out at Jimmy’s. Some were students like Paul Sills [AB’51], who went on to create the Second City. Some were dropouts, like Mike Nichols [EX’53]. Elaine May was sort of a sitter-in-on-classes type. She was a drop-in.

Curtis Black: The last place Charlie Parker played in Chicago was at the Beehive on 55th and Harper. That was the really famous club. It had superstars—Clifford Brown, Max Roach, Gene Ammons. And it was gone in urban renewal.

John W. Boyer: For some people these were the glory days of Hyde Park. The other side is that this was a street filled with gambling, prostitution, and crime.

June Skinner Sawyers: Sometimes the neighborhood tavern could be a bit of a place of disorder.

Jack Spicer: I have always wondered how Jimmy’s survived.

Jack Snapper: Jimmy had a good relationship with the University. This was the sort of bar they wanted. We were in their good graces.

John W. Boyer: The whole block survived. It’s almost a museum piece from the 1920s.

Jack Snapper: To some extent it was luck. Jimmy was a nice guy. They could have picked somebody else.

IV

John W. Boyer on Hyde Park Urban Renewal

Beginning in the early 1940s, signs of serious deterioration in the neighborhood around the University were evident. As a result of the Depression and the war, many buildings had not been maintained for 15 years, and there had been little new investment in the area. In Hyde Park in 1945, 53 percent of the buildings were 40 or more years old; in Woodlawn, 82 percent. Facing serious population shifts and dislocations and rising crime rates in the early 1950s, the University tried to stabilize and rehabilitate the area between 55th Street and 61st Street, from Cottage Grove to Stony Island, and to do so on the basis of economic prosperity and school stability, while seeking to avoid being cast in a racially exclusivist portrait. These plans resulted in the decades between 1960 and 1990 in what Rebecca Janowitz, LAB’70, AM’08, has fairly characterized as a “racially balanced community,” but also a community based on substantial wealth, affluence, and privilege. In doing so, the University engaged in urban renewal involving the lives of several thousand lower-income and (as a majority) African American residents. Under the massive 1958 renewal plan, buildings containing 4,371 families were demolished, clearing approximately 15 percent of the buildings in the plan area, in an effort to de-densify the neighborhood by razing substandard properties. Of these families, 1,837 were White, and 2,534 were Black, making the latter about 58 percent of the total. The social turmoil manifested in these years was bound to elicit strident criticisms about the University’s policies and about its motives that cast a long shadow into the decades ahead.

Jack Snapper: I always wanted to know what would happen if you yelled Fire! in a crowded bar. One time we had a fire in the kitchen. I yelled “Fire!” Everybody laughed.

Joseph G. Peterson: People always used to say, As a writer, you’re lucky to work in a place like this. And I was like, Are you nuts? There’s not a story here I want to remember. When I write my books, it ain’t gonna be about this place. Since then I’ve published nine books, and every single one has been about it.

Sudhir Venkatesh: I used to stop at Jimmy’s on my way home from doing fieldwork. As a researcher I was trying to observe life—like, how do you watch and record and process but not judge? And the folks behind the bar, I felt like they were my teachers. I was learning to be a professional stranger, and they ran a master class.

Jack Snapper: You know, there are people who go to school to learn to be bartenders. I think that means you’re unqualified.

John Davey: They have to mix drinks and do some cooking, but they also have to have conversations.

Vyto Baltrukenas: Jimmy would brag that he put people through college.

Jack Snapper: I was teaching, then bartending until two in the morning and getting to the office at nine.

Matt Martell: I tended bar at the Quadrangle Club in college, and then Bill Callahan hired me. I usually worked nights until 2 a.m. I met the most interesting people.

Joseph G. Peterson: I was at Jimmy’s one night with friends. We were going into the holidays. And I was thinking, god, I just need money. So I said to Bill Callahan, “Excuse me, I’d love to work here part time, if there’s any way I could do that.” And Bill put me in. I must have been 25 years old.

Vyto Baltrukenas: When you were a new hire, you had the talk with Jimmy. He would tell you, I’m paying you this much, don’t drink my imported beers, don’t drink my fancy liquor, and otherwise just try to show up on time. As far as I could tell, it was very difficult to get fired.

Joseph G. Peterson: One day Bill said to me, “Joe, you work behind the bar. Your job is to serve drinks to our customers, who are here for whatever reason brings them here. One thing I would advise is do not judge your customers.”

Matt Martell: As a new hire, Jimmy would take you around the place and show you where things were. A lot of unforeseen situations can happen in a tavern, but he trusted people to figure it out.

Curtis Black: Jimmy was just a straight, regular guy. He took you as you were.

Vyto Baltrukenas: Everybody was welcome, and that came straight from him. He told me: “You treat everybody the same.”

V

He’d study from six till ten every night, then head off to Jimmy’s, where he waited with his friends for the racier members of the faculty to show up. A sociologist of pop culture who’d once worked in the fallen world for Fortune would drink with them some nights until closing time. Even more glamorous was his teacher in Humanities 3, “a published poet” who’d parachuted into occupied Italy for the OSS and still wore a trench coat. He had a broken nose and read Shakespeare aloud in class and all the girls were in love with him, and so was young Zuckerman.

—Philip Roth, AM’55, The Anatomy Lesson

Joseph G. Peterson: A successful bar cannot run without regulars. They are the bread and butter of the business.

David Brooks: I was definitely an Old Style guy.

David Axelrod: “Give me a beer” was my approach. I wasn’t a connoisseur.

Sarah Koenig: I remember being at Jimmy’s a lot. Many important things happened at Jimmy’s.

David Axelrod: I spent way too much time there. It was just the place to go. My wife and I met in a coed basketball game. After the games, we would go over there. I have memories at Jimmy’s that run into the core fiber of my life.

David Brooks: I was a big participant in Doc Films. I would go to the movies at seven, and I’d be done at nine thirty, and then I’d meet people at Jimmy’s. My main memory is sitting at a long table with pitchers of beer, sometimes meeting grad students, or there was an Irish professor who was hanging out there.

Vyto Baltrukenas: Frank Kinahan was a professor in the English department specializing in Irish literature. Popular teacher. He kind of made a home at Jimmy’s.

Joseph G. Peterson: Frank had a drink called a Golden Cadillac. What is a Golden Cadillac? A Golden Cadillac is a beer, probably Miller Genuine Draft, poured into a Tom Collins glass and served on a coaster.

Curtis Black: Frank was a sweetheart, the kind of guy you’d love to run into in a bar.

Joseph G. Peterson: Frank loved Seamus Heaney’s poetry. I remember him reciting one poem about a man and a wife hanging a bedsheet. They would pull it off the clothesline and fold it, the two of them, and as they folded it, they’d get closer and closer. It was a sort of dance. And that’s what the poem was trying to evoke, the dance around this domestic chore.

Vyto Baltrukenas: I’m working one afternoon, and Frank and three or four other people are sitting in one of the booths. The phone rang and I picked it up: “Is Frank Kinahan there?” I handed the phone to Frank, and he talked for a few minutes, came back and said, “I’d like to buy the bar a drink. I just got my tenure decision.”

Bill Callahan: David Grene used to sit in the middle room and drink Tanqueray martinis with Saul Bellow.

Joseph G. Peterson: You’d serve him his hamburger and his martini: Here you go, Mr. Grene. He’d sit down at the table with his graduate students. And if there weren’t any students, he’d just read a book. I’d say, What are you reading? It was always the same thing: the plays of J. M. Synge. He just sat there and read J. M. Synge.

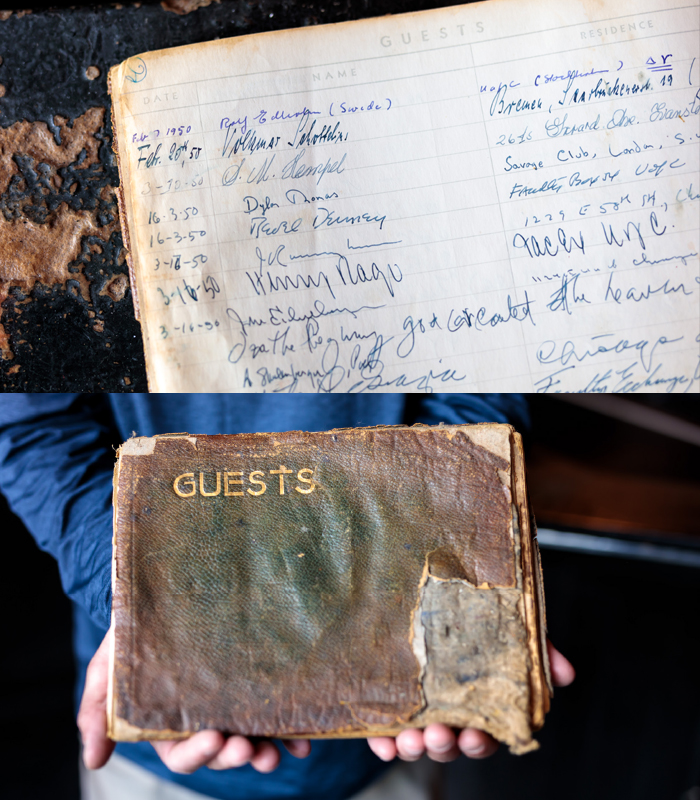

Matt Martell: I served afternoon martinis to David Grene. He usually sat in the front middle room. He never signed Jimmy’s guest book, as far as I know. Jimmy started having customers sign a leather-bound guest book in the early ’50s. Dylan Thomas, Mike Royko, Jimmy Breslin.

Joseph G. Peterson: Jimmy told me that Dylan Thomas stayed at the Quad Club once, and he came in at lunchtime and ordered a drink, after which he put the glass down. Then he ordered another drink and put the glass on top of the previous one. Then he did it again. And again. Jimmy said he just stacked glasses throughout the afternoon and into the night.

There were a few people who were acolytes of Norman Maclean [PhD’40], who I think lived across the street. I never saw the guy come in, but they would always talk about him. You know, Will he come today? Kind of like The Iceman Cometh.

David Axelrod: There are other saloons that can claim celebrity patronage, but unless they’re in Oslo, probably not as many Nobel Prize winners. Including Barack Obama, for crying out loud.

Bill Callahan: He used to go in the middle room, when that was the only smoking room. You had a certain amount of space there.

David Axelrod: It was a place to let your hair down.

Jack Spicer: I was a landscape contractor in Hyde Park for 45 years. When my day was over, I might walk into Jimmy’s looking filthy, sit down and have a beer. Never bothered anybody.

Sudhir Venkatesh: There’s this line in Nelson Algren’s The Man with the Golden Arm: He was a man like any man, with a bit less luck than most. And I feel funny saying it, because it’s the University of Chicago, but Jimmy’s allowed you to just drop the pretense and just kind of bond over your frailties. You didn’t have to try. You didn’t have to worry about what you could have been. You walk into Jimmy’s and it’s like everyone’s in their underwear in the waiting room at the doctor’s office.

Stephen Anderson: That’s the main thing: it didn’t matter where you came from or your pedigree. You could come in and get into some interesting conversations.

Jack Spicer: Everybody feels welcome, which is actually a hard thing for a community to accomplish.

Nina Helstein: Jimmy’s is a community and a home. I wasn’t much of a drinker, but that wasn’t why I came to Jimmy’s.

Jack Snapper: I kept trying to tell Jimmy, You’ve got four rooms here. Take one and make it nonsmoking. You’ll get more people. And Jimmy would say, No, people smoke in bars.

Joseph G. Peterson: Even smokers would go outside. You’d leave work stinking so much that I’d actually strip out of my clothes, put them in my trunk, and drive home.

Jack Spicer: If I stopped for a beer after work, I would go home and my wife would say, Oh, you’ve been to Jimmy’s?

David Axelrod: Air quality was not a thing. And if it was your thing, they’d sort of shrug and tell you to go somewhere else.

Joseph G. Peterson: There was a big cigar craze in the 1990s. All the B-school guys would come into the west room and light up cigars. We found out later that the air ducts were clogged. It was an OSHA nightmare.

Matt Martell: Since the indoor smoking ban in 2008, visibility in the bar is much improved.

Vyto Baltrukenas: Jimmy had been having some issues and had slowed down. But nobody thought he was near.

Jack Snapper: You know, the Callahan brothers, pretty much one or the other of them was always there. The Callahans were smart, and they kept the place. Jimmy didn’t have to be around.

Carole Rich: My dad had had a couple of operations. His hearing was always bad, but he managed. A lot of times he was reading lips.

Vyto Baltrukenas: He went through health issues. The man had, what, four or five cornea transplants? He always appreciated his hearing aid. I can turn this off if I don’t want to listen to you anymore, he would say.

Carole Rich: My mother passed away in 1992. When she died … broken heart. Fifty-eight years, you know. That’s a long time.

Vyto Baltrukenas: We had the bar’s 50th anniversary in 1998. Jimmy put himself at table 1 at the north end and kind of stood there as people wandered in. And pretty soon the place filled up. Everybody just had to come by and say hi.

Matt Martell: Jimmy loved being in the bar and talking with customers, but he didn’t come in as often in his last few years.

Vyto Baltrukenas: I walked into the bar one morning and the crew told me they had just gotten a call and Jimmy had passed away. Totally unexpected.

Matt Martell: A few months after Jimmy died, the bar’s liquor license was supposed to expire. So Bill and Jim applied for a new license and waited.

Vyto Baltrukenas: One day I opened the mail and said, Oh, a letter from the City. “Your application has been denied,” it read. In those days there was kind of an anti-liquor-license movement in the city. Many places, particularly smaller places, lost their license or didn’t have it renewed. The commissioner came to Jimmy’s and discovered we were too close to the school.

Matt Martell: The bar also needed renovations to bring it up to code. New walls, floors, bathrooms, kitchen, electrical, plumbing—basically everything.

Vyto Baltrukenas: We spent the summer tearing the place out. Only the ceiling in the west room was left over. And the bar, which is from the ’20s, we think.

Matt Martell: But after all the renovations, the City denied the application again because of the bar’s proximity to St. Thomas the Apostle School across Woodlawn Avenue.

Vyto Baltrukenas: We had heard that something was amiss.

Jack Spicer: The bar was probably in more jeopardy than we realized.

Vyto Baltrukenas: We had an appeal hearing on March 17, St. Patrick’s Day. We rode the train downtown. There were all kinds of people at the hearing. The University, neighborhood groups, significant folks in the state government. Religious institutions.

David Axelrod: There are a lot of old Irish priests who probably would smile knowing that the church saved Jimmy’s.

Vyto Baltrukenas: We didn’t organize anything. People just came down. I looked around and said, My god, I’ve been here for 20 years, and I don’t know all these people. We were flabbergasted. A few weeks later we got a decision.

VI

License Appeal Commission Order (March 22, 2000)

Well run taverns operated by good neighbors can enrich a community greatly. It is apparent that Jimmy’s has been enriching this neighborhood as a meeting place for the community since the middle of the last century. It strikes us as a place where hard hat and lunch pail share the same bar with briefcase and Wall Street Journal, where a shot and a beer is as at home as a glass of Cabernet. It also seems to be a place that fosters good times and fond memories for people who may subsequently leave this community behind to pursue a career but will never leave behind the collegiate experience that this tavern is itself a part of.

Bill Callahan: The busiest day we ever had was the last day we were open in 1999. And a busier day than that was when we reopened. I’d come in at seven and work till three or four in the morning. It was insane.

Vyto Baltrukenas: The joy that you saw. People flew in just to be here. We’re talking about 50 years’ worth of Jimmy’s ownership. The number of people who considered themselves regulars, even if they weren’t there every day. People who met their wives, girlfriends, husbands, boyfriends, whatever. Births, deaths.

Hanna Holborn Gray: I spend a lot of time meeting with alumni, sometimes quite by accident. I never go to an airport or a restaurant without meeting graduates of the University of Chicago, and so many of them mention their time at the University. And Jimmy’s crops up. They want to know how it’s doing.

Joseph G. Peterson: When I left Jimmy’s, for many years my habit for falling asleep at night would be to walk behind the bar in my mind and remember, you know, where to pop open the beer bottles, how to empty those things out, just walking through the bar, remembering all the little details.

Vyto Baltrukenas: If I hadn’t gotten that job, maybe I’d have gone out and made a million bucks. But I’m willing to look on the bright side and say, I got to know Jimmy instead.

Joseph G. Peterson: There’s a perfect moment to the day in a bar, in my opinion. It might be just after lunch or something, the way the light comes in. It’s still a little quiet. You’d have your lunch crowd, mostly construction workers, a handful of regulars, some professors. Friday evening if you open the west room, maybe five or six in the evening, was perfect. It was quiet, mellow. You’d have a person here or a person there. And then by six all the workers are coming in and everybody’s just talking, you know, talk, talk, talk. And it’s still quite nice. But once you serve five or six pitchers, the volume, and before you know it everybody’s shouting.

Ben Ryder Howe, AB’94, is a writer in New York City. He is a frequent contributor to the New York Times and the author of My Korean Deli: Risking It All for a Convenience Store (Henry Holt, 2011), which is being made into a television series by AMC Networks.