(Photo courtesy Benjamin Recchie, AB’03)

Meet the undergraduate cruciverbalists who design puzzles for the Maroon, Family Weekend—and occasionally the New York Times.

I started solving crossword puzzles when I was a teenager, leaning over my mom’s shoulder at breakfast, taking pride in finishing it with her without resorting to a puzzle “cheat book” like the thick, well-thumbed, nicotine- and coffee-stained paperback that sat next to my grandmother’s chair. But when I went to college I fell out of the habit. I would glance at the puzzle section as I skimmed the paper … but “Who has the time?” I would ask myself.

Little did I know that not only do some UChicago students have the time to solve their daily crossword puzzles—they also make time to build them.

There’s a story I heard over and over again from the nucleus of undergraduate puzzle creators: they liked crosswords before COVID-19, but they didn’t start constructing puzzles themselves until they were bored out of their skulls during the pandemic.

Pravan Chakravarthy, Class of 2025, began creating puzzles around May 2020: “The combination of trivia and wordplay and logic was exactly what I liked to do.” He started with mini crosswords (typically 5" × 5"), then progressed to full-size puzzles (usually 15" × 15" in weekday editions of newspapers and 21" × 21" on Sundays). “I realized that, oh, these aren’t just AI generated,” he says. “A lot of thought and effort and artistry is put into them.”

Garrett Chalfin, Class of 2027, fell in love with crosswords while at sleepaway camp as a kid and even submitted an early attempt to the New York Times in the seventh grade. But it wasn’t until COVID hit that he revisited the idea. In a “hopelessly bored state,” he says, he was scrolling through his computer apps and started tinkering with the crossword puzzle software. This time, his imagination caught fire.

“COVID really gave me the time to dive into it,” says Henry Josephson, Class of 2025. “I was like, it can’t be that hard to make these things. I solved them all the time. It’s just a bunch of words in a grid, right?” The ones in the New York Times, he discovered, are “just crossword puzzles that people made and sent in,” he says. So he searched for puzzle construction software online and started building his own.

Crosswords were instrumental in bringing Josephson to UChicago: he wrote his application essay about them. He intended to join the crossword puzzle club, but it turned out to be moribund.

There was one graduate student, Chris Jones, SM’19, PhD’22, who contributed an occasional crossword section to the Chicago Maroon, but even that was “a little more dead than I realized,” says Josephson. Jones asked Josephson and Chakravarthy—who had met on Instagram as incoming students before arriving on campus—if they had an interest in reviving the section.

“We looked at each other. We were like, yeah,” Josephson says. “There were never any tryouts, never any leadership struggles or anything.” Chakravarthy became the Maroon’s head crossword editor; Josephson, crossword editor.

Together they’ve developed a UChicago-specific word list “so that we can have MANSUETOs and WOODLAWNs and SOSCs,” Josephson says. And SCAVHUNT, of course.

Creating puzzles for yourself is nice, but it’s nicer to see them shared with the world. Josephson notes that he and Chakravarthy have an obvious outlet in the Maroon, and they’ve recruited other crossword creators on campus, including Eli Lowe, Class of 2027. “I didn’t even consider creating puzzles until I found out that the Maroon had a crossword section,” Lowe says. “I decided to go to a crossword section meeting and instantly was hooked. Creating puzzles scratched that same itch that solving them did, but to a much greater degree.”

But there’s no bigger feather in one’s cap than the New York Times crossword. Not only is it the most prestigious, but it also pays well—up to $2,250 for a Sunday puzzle from an experienced contributor. Most publications pay a fraction of that; Chakravarthy notes, “If you want to make a living doing crosswords, you have to be an editor.”

The Times’ crossword editors will also give feedback on a rejected puzzle, allowing novice constructors to hone their craft. Josephson recently received a rejection from the NYT that focused on the number of proper names crossing each other, which can trip up puzzle solvers if they’re at a loss for both names. Other papers, such as the Los Angeles Times, don’t pay as well; however, as Chakravarthy explains, because they get fewer submissions, they can offer even better, more detailed feedback.

Several Maroon crossword contributors have been published in the New York Times, most notably Chalfin, who had two Sunday puzzles published last year. David Litman, Class of 2027, has also been published in the Gray Lady. Chakravarthy has not had a puzzle in the New York Times—yet—but he has been published in the Los Angeles Times and Universal Crossword, which syndicates its puzzles to newspapers across the country. And just as this story was going to press, Josephson had his first puzzle accepted by the New York Times.

No student, however, has seen as much success as UChicago’s provost Katherine Baicker. Her puzzles have been published not only in the New York Times but also the Boston Globe and the Wall Street Journal, to name a few. And like the students, she created her first puzzle in January 2021, when she had more free time in the evenings due to the pandemic.

It’s never been easier to build a crossword puzzle. As recently as the 1990s, puzzles were put together through trial, error, and artistry. But the rise of easy-to-download crossword puzzle software with names like CrossFire and Ingrid (get it? get it?) has put puzzle creation within reach of the interested amateur.

In Josephson’s Maroon bio, he states that he “would love to build a crossword puzzle with you. Seriously. Let’s find a time.” I asked him if the offer was still good. “I’m definitely still interested!” he replied. (He also noted that no one else had ever asked: “The set of people reading Maroon bios is probably pretty small.”)

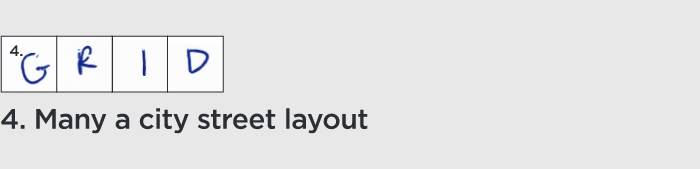

Josephson and I settled on a rough plan: we would choose a theme, then he would put the theme answers into a symmetric grid and build out the black squares. He would use Ingrid to fill out the remaining squares and edit them. Finally, we would work on the clues together.

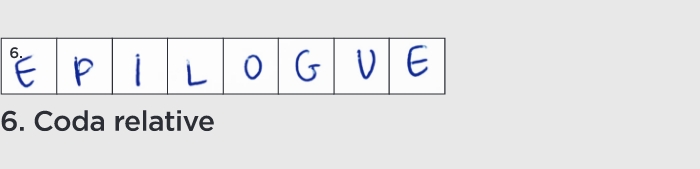

Before you go any further: the remainder of this section contains details of the creation of the crossword puzzle you can find here, and therefore is rife with spoilers. If you plan on solving this puzzle, go off and do it now. I’ll wait.

*whistles softly*

Okay, finished? Did you beat the time of University of Chicago Magazine editor Laura Demanski, AM’94, who solved it in 14 minutes and 39 seconds? If so, well done.

Right—here we go.

Josephson and I started by brainstorming the theme. (As Lowe puts it, a good puzzle prompts you to “think laterally” and leads to “really rewarding aha moments” even as “it is important for the theme to not be too forced.”) We independently landed on the idea of the theme for the puzzle being something related to the Core. Josephson suggested words where the clue contained “core”—think BODYBUILDER—but I proposed the opposite, with answers that contained “core” (or a soundalike syllable, like MARINECORPS). Josephson was skeptical, but gamely promised to try both approaches; as it turned out, he said, my idea grew on him as he was building out the grid. The trick is to come up with words that not only fit with the other words but also are novel enough to be fun.

(Chakravarthy described to me three things he steers clear of in his own puzzles. One, “unfair crossings,” where two obscure answers cross—think proper names. If you have no idea of the answer, you’re completely stuck. Two, “crossword glue,” which he describes as “answers that you only see in crosswords,” such as ULU, a traditional Inuit knife, or “obscure European rivers” like Switzerland’s AARE. And three, duplicates within the same grid. “This just happened to me the other day,” he says. “I didn’t realize it until I was halfway through clueing.”)

In no time, Josephson produced the puzzle you see here.

The next step was to write up the clues: “The most creative lateral thinking part with the fewest constraints,” he says.

I’ve written a lot of trivia questions in my time—like, a lot—and here I felt I could truly contribute. But I had to avoid the classic trivia trap of writing an impossible question to show off how smart you are while stumping the player in the process. (Fun lives in the narrow space between “too easy” and “too tough.”)

For example, I initially clued 5 Down as “1982 Duran Duran hit,” but Josephson gently reeled me back in: “I’m not sure what the average age of Core readers is, but I also worry about people getting this.” (The answer, if it had made it into the puzzle, was RIO.) And while I was certain that people would easily get 59 Across with the clue “Respighi subject,” even Josephson had to Google that one. (You knew it was PINES, right, as in “The Pines of Rome?” Of course you did.) Back to the drawing board.

Meanwhile, I struggled to find clever ways to address some otherwise common words, such as 51 Down, KNEE. Josephson covered for me by filling these out (including ones more relevant to the younger alumni, such as 49 Across, in which one SUBMITS to Canvas). And I confess that I got a warm fuzzy feeling when he wrote “I like this a lot!” next to my clue for 30 Across: “Follow-up to a good drive.” (That’s PUTT, naturally.)

My sole disappointment: he didn’t use one of my suggested answers, CORREGIDOR. (My proposed clue: “The Core, besieged by the Japanese.”) Oh, well. Maybe next puzzle.

I asked Josephson how he’d score our puzzle on a scale of 1 to 10, with 10 being the Platonic ideal of a crossword and 1 being something not even worthy of a placemat at Denny’s. “I’d probably rate this around a 5,” he replied. “I don’t think I’d submit this grid if I were hoping to sell it to a publisher like NYT or WSJ, but I’m also not ashamed to have my name attached to it.” (“My biggest gripe is that theme is pretty basic,” he explained, so that’s on me, readers.)

And to all who think you can do better—well, the software is online. Give it a try!

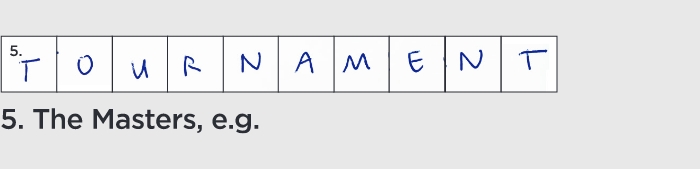

In October of 2022, Chakravarthy and Josephson held a crossword tournament at Family Weekend. (“We didn’t ask for any permission from anyone and just booked a room, made some grids and posters, and kicked it off,” says Josephson, although the next year’s iteration was held in cooperation with College Programming and Orientation.) Over three rounds, individuals or groups (there were many student-parent team-ups) competed to complete three crossword puzzles with the least time elapsed and the highest accuracy. While it might sound tense, “it’s supposed to be casual, and for anyone who wants to just solve some puzzles,” Chakravarthy says. “People have competed for just the third puzzle and solved it in like 10 minutes. And people have competed in all three puzzles and used all the time.”

And for the winners, says Josephson, “We mention them in the [Maroon] (assuming they’re okay with it), and the prize is a custom puzzle!”

It’s proven quite popular: the 2023 edition of the tournament had roughly 150 contestants. “I can’t wait to do it again for the fall,” Chakravarthy says. Further plans might include an expansion to Alumni Weekend as well, so keep your eyes peeled and your pencils sharpened.

“One of the beautiful things about UChicago is that if you are interested in a weird, niche, nerd thing,” Josephson says with evident delight, “there are several other people here who are also interested in it and are maybe better at it than you.”

Chakravarthy recognizes that he occupies an enviable seat at the Maroon, where he and Josephson can publish their own work without limit. After they graduate, though, that outlet will dry up. He says he might publish his puzzles—ones that he doesn’t get published elsewhere, that is—on a private website: “There’s going to be potentially a lot of unpublished work that I’ll be producing.”

For Chalfin, creating the puzzles is its own reward. “I enjoy writing puzzles because no two puzzles are the same. Each one excites me and presents my brain with a unique challenge,” he says.

“There is no better feeling when, after hours—or days, or weeks!—of work, I finally look at a finished puzzle of my own creation. Something I’ve done.”