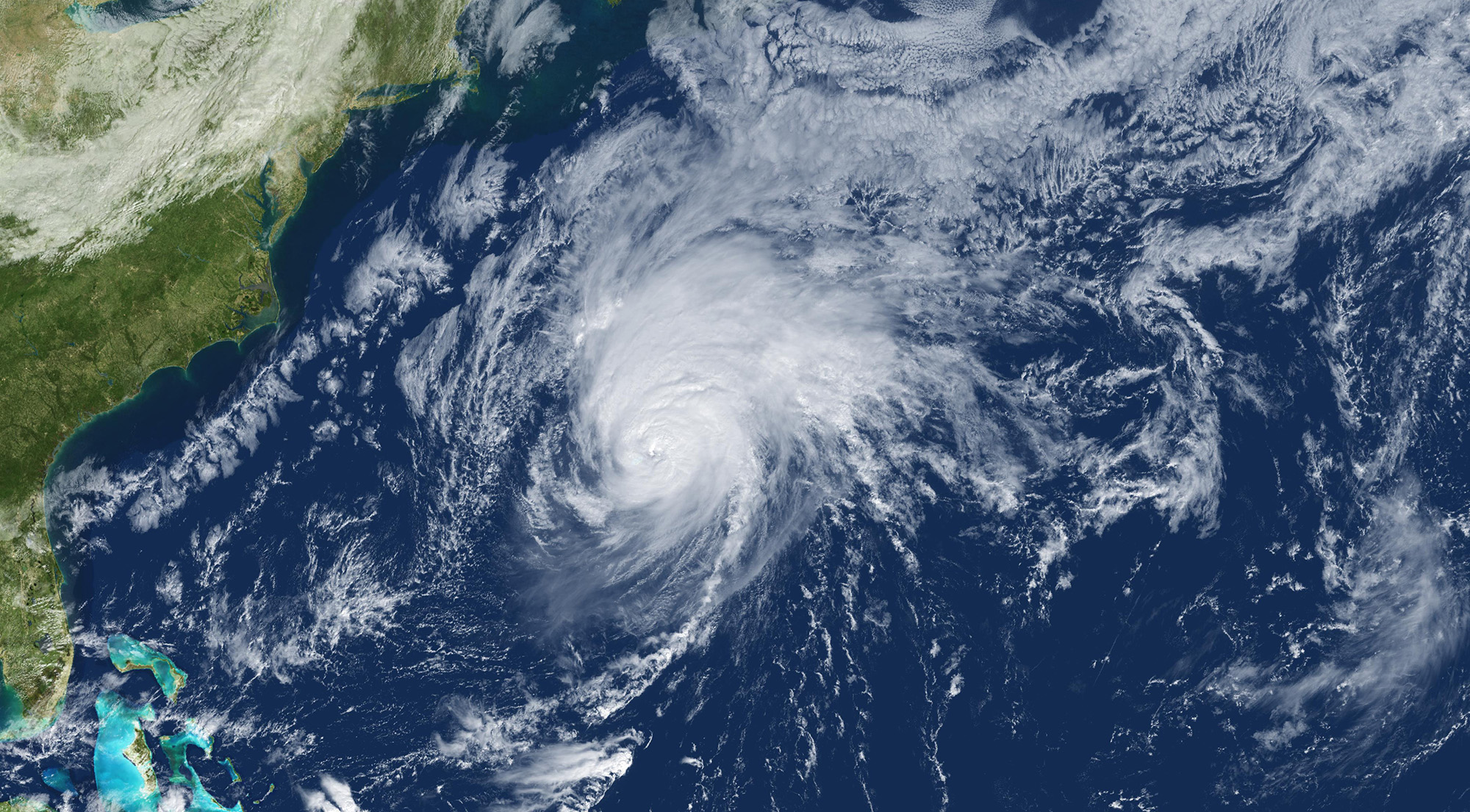

This image, from October 13, 2016, shows Hurricane Nicole as it was ravaging Bermuda. By analyzing samples from sediment traps in the deep ocean near Bermuda, researchers found that hurricanes supercharge the carbon cycle, pushing much more organic material into deep waters. (Photo courtesy NOAA)

New findings on algorithmic bias, ultrathin films, the lingering damage of hurricanes, and what we donʼt learn from failure.

Stormy outlook

The destructive power of hurricanes extends deep into the ocean, according to a recent study by scientists at the Marine Biological Laboratory. Published August 16 in Geophysical Research Letters, the paper provides evidence that hurricanes affect the ocean’s biological pump—the process that transports carbon into the deep ocean, where some of it remains sequestered. By analyzing samples from sediment traps in the deep ocean near Bermuda, the site of Hurricane Nicole in 2016, the researchers found that hurricanes supercharge the carbon cycle, pushing much more organic material into deep waters. With the number of severe hurricanes on the rise, that’s potentially worrisome news. The global climate and the health of the seas depend on a delicate balance of carbon in the deep ocean—and it’s not clear how the addition of so much extra carbon will affect that equilibrium.

Algorithmic bias

Hospitals nationwide use high-risk care management programs to provide extra support to patients with complex needs. Many providers rely on predictive algorithms to identify candidates for these programs. The problem, according to an October 25 Science study, is that one widely used algorithm is inadvertently biased against black patients. Drawing on data from a major academic hospital, Chicago Booth’s Sendhil Mullainathan and coauthors discovered that black patients were much sicker than white patients with the same risk score. Why? The software used patients’ predicted health care costs as a proxy for risk—but less money is spent on black patients than white patients overall because of unequal access to care. If the system included other variables, such as chronic conditions, the percentage of black patients receiving additional care would rise from 17.7 to 46.5 percent.

Film studies

Electronics have gotten smaller in part because scientists found ways to squeeze circuitry onto ultrathin layers of inorganic materials. Now a team of scientists have developed a method of growing equally tiny layers of organic (that is, carbon containing) materials. The atoms-thick films have a variety of possible applications, including use in novel fabrics, water filters, or sensors. The researchers, including chemist Jiwoong Park of Argonne and the Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering, published their findings in Science December 13. Creating the films involved injecting ingredients in the space between two liquids that don’t mix—think of the line that forms between oil and water. Then the researchers evaporated or drained the liquids, leaving behind only the flat, delicate film. Among other intriguing properties, the material is able to effectively store electrical energy.

Failed by ego

Failure is not always the great teacher it’s cracked up to be. That’s according to a paper from Chicago Booth’s Ayelet Fishbach, published November 8 in Psychological Science. Fishbach and her coauthor found that failure actually diminished the ability to learn. Across five experiments, 1,674 study participants received a set of unfamiliar questions (in one instance, about ancient languages) with two possible answers, followed by feedback on their responses. When presented with the same questions later, participants who had failed the first time around did not improve—even though they had all the information they needed to ace the test. The phenomenon stems from bruised egos, the researchers propose: when our balloon is punctured, we lose interest in the task and don’t retain information. But it is possible to learn from failure when this ego threat is removed: the study found that participants did learn from watching other people’s struggles.