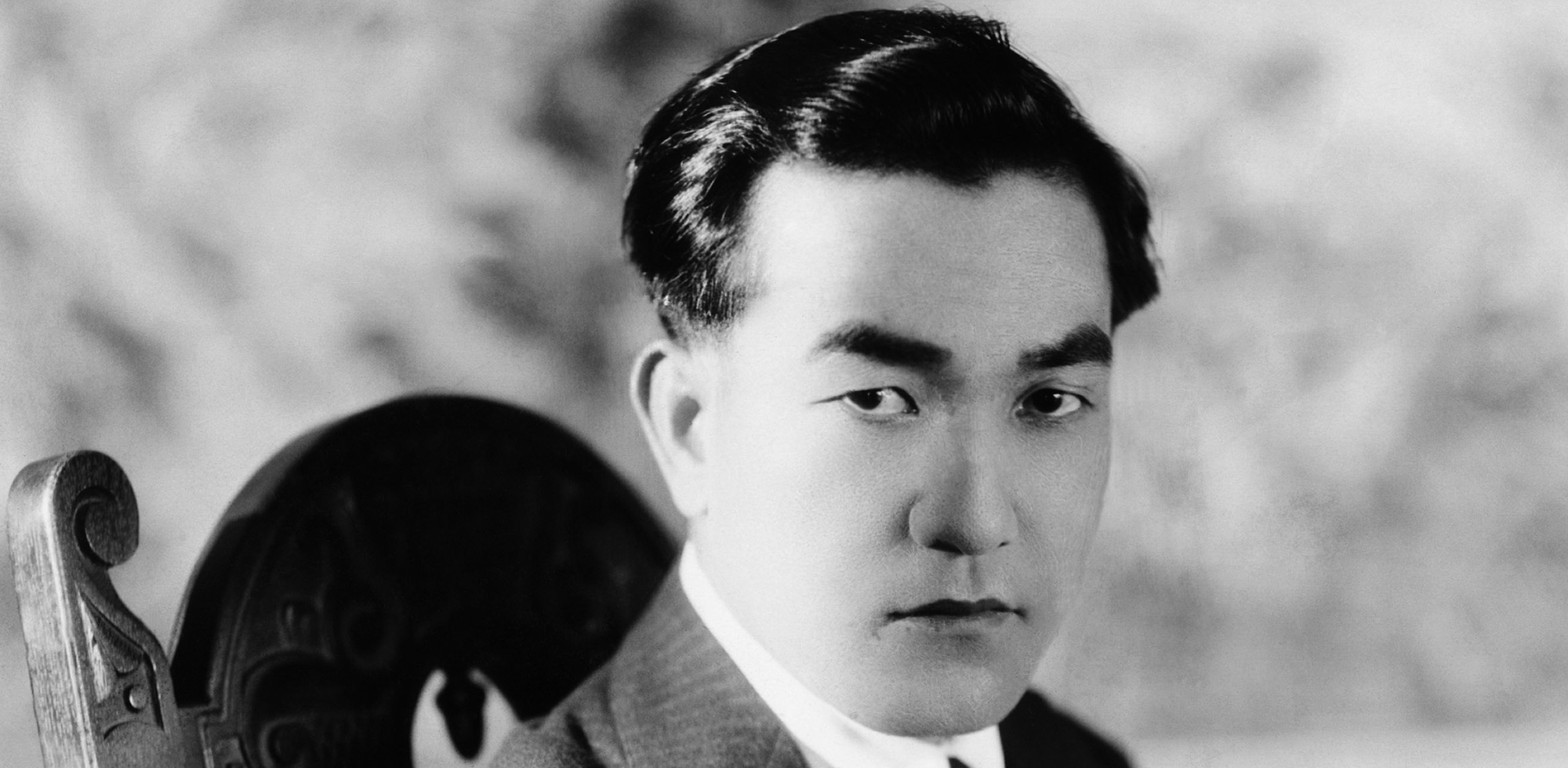

From this magazine in the 1920s to the New York Times when he died in 1973 to current accounts, Hayakawa’s UChicago bona fides have been widely accepted. (Everett Collection)

Matinee idol and Oscar nominee Sessue Hayakawa is widely remembered as a UChicago alumnus. But was he? We tried to separate fact and myth in the storied actor’s biography.

A giant of the silent screen whose career stretched into the sound era, Sessue Hayakawa starred in more than 100 movies. Perhaps best remembered today for his Oscar-nominated 1957 performance as Colonel Saito, the Japanese commandant of the prison camp in The Bridge on the River Kwai, Hayakawa was the only Asian actor to play romantic leads in American silent pictures—although because of anti-miscegenation laws he always had to relinquish the girl in the final reel.

Hayakawa’s place in motion picture history is well documented. Harder to know is the man behind the legend. Even harder to untangle is the star’s status as a UChicago alumnus.

Born Hayakawa Kintaro in 1886, the son of a wealthy fisherman in Japan’s Chiba Prefecture, he came to the United States in 1907 to join his brother, who was fishing for abalone in California. The following November he enrolled in two Principles of Political Economy correspondence courses offered by the University’s Home Study Program. The registrar’s office has no record of his enrollment in any courses held in Hyde Park.

In his 1960 memoir, Zen Showed Me the Way … to Peace, Happiness, and Tranquillity, Hayakawa tells a very different story. He details his life on campus, including two seasons as a 132-pound tackle for the football team under coach Amos Alonzo Stagg. After using illegal jujitsu manuevers too many times, he writes, he was kicked off the team. But Hayakawa appears on no team rosters—or anywhere else—in the Cap and Gown yearbooks of the day.

Hayakawa seems to have inflated and elaborated the University connections he wove into his life story, and his version of that story has stuck—leading the actor’s narrative to become embedded in the University’s as well. His myth making offers a lens on American and Hollywood culture during his lifetime.

Hayakawa claims to have left Chicago for California in 1913, intending to return to Japan. But, he wrote, after seeing a play at a Japanese theater in Los Angeles’s Little Tokyo district, he canceled his ticket and joined the company, despite having no acting experience. Dropping the name Kintaro for Sessue, he staged an English-language play with an all-Japanese cast.

The play caught the eye of producer Thomas Ince, who turned it into a silent film. By 1914, Hayakawa writes, he earned $1,000 a week making movies, an amount he deemed sufficient to allow him to marry Tsuru Aoki, an American-raised Japanese stage and screen actress.

According to Daisuke Miyao, professor of Japanese language and literature at UC San Diego and author of Sessue Hayakawa: Silent Cinema and Transnational Stardom (Duke Unversity Press, 2007), Hayakawa’s turn to acting was in reality less dramatic. It followed a series of odd jobs in California: dishwasher, waiter, ice cream vendor, and factory worker. His theatrical appearances seemed like another temporary pursuit. Both memoir and Miyao agree that the movies Hayakawa first appeared in were Ince’s.

In those short films, the actor portrayed Native American and Japanese characters, but never in a starring role. In 1915 he left Ince for the Jesse L. Lasky Feature Play Company—later Paramount. There Cecil B. DeMille cast Hayakawa in The Cheat (1915), and a matinee idol was born.

In contrast to the broad pantomime then common in Hollywood, Hayakawa played to the camera instead of the balcony. His acting stood out for its restraint; audiences knew how he felt because of the subtle play of emotion across his features in close-ups.

In The Cheat, Hayakawa’s coolly wicked Japanese ivory merchant lends money to an American socialite who has gambled away Red Cross funds entrusted to her. When she attempts to repay him in cash instead of the more personal compensation she’d promised, Hayakawa’s lecherous villain brands her bare shoulder with the mark he uses to identify all his possessions.

The scene elicited screams of ecstasy from the audience; some women fainted. Hayakawa’s effect was said to be even more electric than that of Rudolph Valentino in The Sheik six years later.

Following The Cheat, Hayakawa’s silent film roles hewed closely to Western stereotypes about Asians. The late film historian Robert Sklar once quipped, “He was a valet; he was a valet who was also a spy; he was a spy who was also a diplomat. (He does not seem to have played a University of Chicago graduate.)”

Hayakawa saw his roles as an opportunity to dispel stereotypes of the “Oriental” as sinister and mysterious. He also played other ethnicities: a Mexican bandit, a Spanish matador, a Persian author. From 1916 to 1918—a period of growing US nativism—he became an unlikely leading star and the industry’s go-to exotic. Theaters advertising Hidden Pearls (1918), in which he plays the son of a Hawaiian princess and an American trader, were encouraged by a trade journal to use the phrase “Sessue Hayakawa adopts another nationality.”

In March 1918, when his contract with Lasky expired, Hayakawa formed Haworth Pictures Corporation, Hollywood’s first Asian-owned production company. His strategy at Haworth, Miyao writes, “was a simultaneous campaign of winning the hearts of American audiences by clinging to his already established star image and convincing Japanese American communities of his more authentic depiction of Japanese characters.”

Around this time Hayakawa went full Hollywood, according to fan magazines and his memoir. He purchased a mansion, took up golf, threw parties with bootleg liquor he’d wisely laid in before Prohibition began, and bought two Cadillacs, a Ford, and a gold-plated Pierce Arrow. The magazines reported breathlessly about the actor and his wife, who were active in Liberty bond drives during the First World War.

The showy lifestyle was in part a response to rising postwar anti-Japanese sentiment in California, intended to show Americans he could live up to their lavish standards. But however Hayakawa tried to demonstrate his Americanness, his popularity couldn’t survive increasing nativist sentiment in the United States. By the time he left Hollywood in March 1922, he had lost control of both his star narrative and his company.

Now a “free agent,” Hayakawa wrote, he visited Japan, acted in French and British movies, and gave a 1923 royal command performance before King George V and Queen Mary of England.

Returning to the United States in 1926 to appear on Broadway—and later in vaudeville and his first talkie—Hayakawa opened a Zen temple and study hall on New York’s Upper West Side. He then lived in Japan before finding himself trapped in Paris during World War II, where he’d gone to shoot a movie. As a Japanese national with a long career in the United States, Hayakawa was suspected by both sides.

Even so, Hollywood came calling once more when Humphrey Bogart, a fan, cabled him to offer a part in Tokyo Joe (1949). He took the role but would spend most of the rest of his life in Japan. There, he writes in his memoir, his long study and practice of Zen, and particularly his work on its behalf in the United States, prompted Tokyo’s Zen masters to choose him to enter the priesthood.

Miyao isn’t so sure. Like his University of Chicago education, Hayakawa’s Zen priesthood seems well tailored to fit a persona he wanted to promote. “I think the life of Hayakawa as a star was always a process of creating his own myth,” says Miyao.

When invited to join the cast of The Bridge on the River Kwai, Hayakawa was living largely out of the public eye. The role of Colonel Saito appealed to him: not a sympathetic character but a decent man. The performance thrust the actor back into the spotlight, and he made seven more films, the last released in 1967. He died six years later at the age of 83. Hayakawa’s own account of his early years in the United States, buttressed by decades of publicity, proved convincing enough that his New York Times obituary noted that—as recorded in his memoir—he graduated from the University of Chicago in 1913.

Amy Monaghan, AM’93, teaches film at Clemson University.