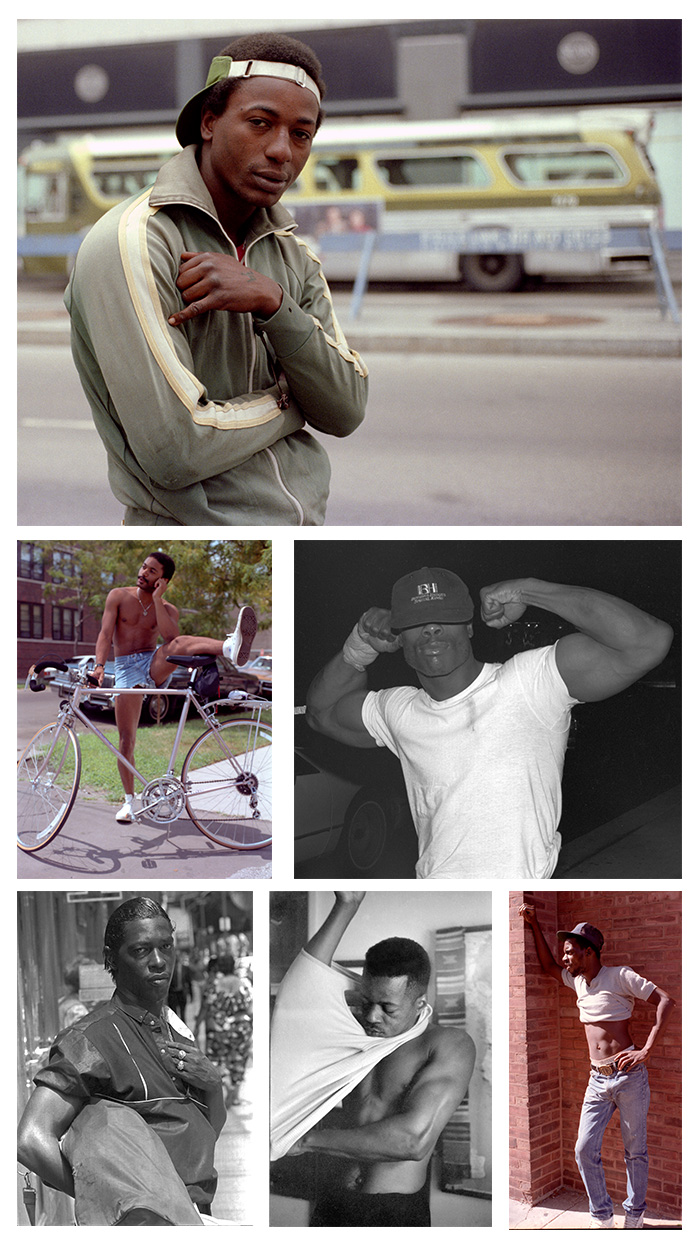

Patric McCoy, AB’69, strikes a pose on Chicago’s lakefront bike path. (Photography by Terry Smith)

As Patric McCoy, AB’69, cycled to work, men called out to him to take their picture. So he did.

In 1984, on his birthday, Patric McCoy, AB’69, “wrote out a commitment,” he says. He wanted to teach himself photography. So he resolved to carry a 35mm camera with him everywhere—hanging around his neck, where it was very visible—and to take photographs every day. And if anyone asked him to take their picture, he would. “Why I wrote that, I have no idea,” he says. He did include “a little clause that if it was a dangerous situation, I could possibly pass on it. Otherwise, I had to stop.”

McCoy, who had majored in chemistry, was working at the Chicago office of the Environmental Protection Agency; even in the early 1980s, he was well aware that “we have to save the planet,” he says. So he gave up his car and commuted by bicycle from his South Shore home to the Loop. He used the lakefront bike path at first, but he “got tired of looking at the same trees.” He preferred to ride through the neighborhoods, varying his route depending on his mood.

All along the way, people—almost always men—would shout at him, “Hey! Take my picture!” McCoy would stop, get off his bike, and take a photograph. He never directed his subjects to pose or smile or do anything in particular. “I just took the picture,” he says. “My intent was to take the best picture, given what they present.”

McCoy’s father, a self-taught artist, had built a darkroom in his basement; every night McCoy would go there and develop the photographs he had taken. He would make two black-and-white, five-by-seven copies: one for himself, one for the subject. He carried the stack of prints around in his backpack, and if he saw someone he had photographed, he would give them a print—to their astonishment. The film stock of the time did not capture darker skin tones well, he says, “so most of these people, if they had any photographs of themselves, did not look very good.” And yet here was a stranger giving them “a good photograph of themselves.”

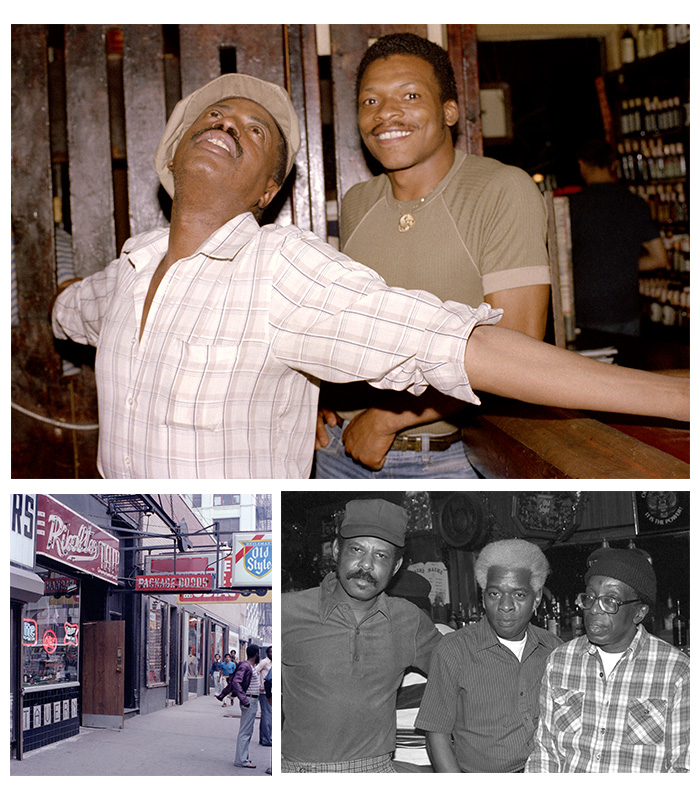

McCoy also frequently took pictures of men he knew from the Rialto Tap, a South Loop bar that stood near State and Van Buren, where Pritzker Park is today. The bar—just around the corner from the EPA—served a motley crowd, including professionals like McCoy and unhoused men who stayed at the nearby Pacific Garden Mission. “It was a very, very friendly place,” says McCoy, who calls it “the Black Cheers. Everybody knew everybody.”

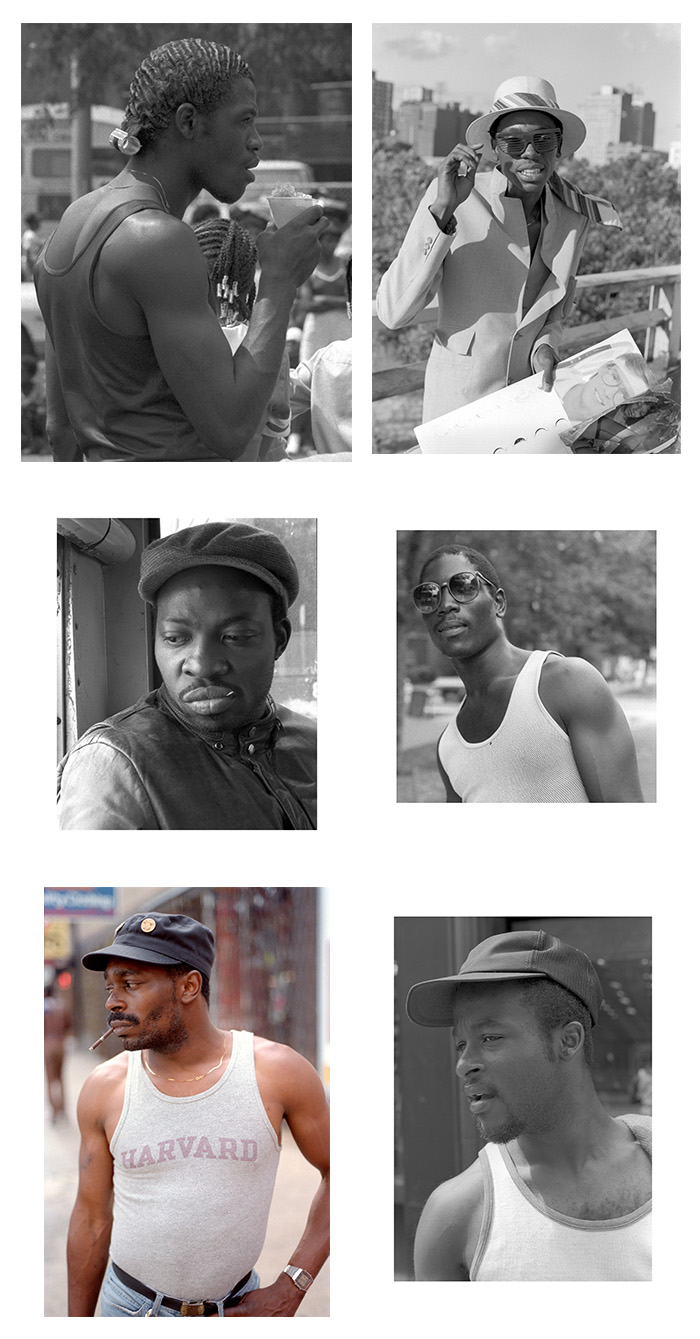

This past summer, a sampling of the thousands of images McCoy shot during the 1980s was shown in the exhibition Take My Picture at the North Side gallery Wrightwood 659. “McCoy and his camera fulfilled an unspoken need for Black men to be seen,” according to curator Juarez Hawkins—“seen by someone who did not objectify them as ‘Other,’ but an insider who allowed them, paraphrasing Langston Hughes, to be their ‘beautiful black selves.’” After the exhibition closed, a smaller version was staged at the Hyde Park Historical Society. McCoy is also working on a related book.

Read more about McCoy in this 2019 profile from the Core: “Art Me Up.”