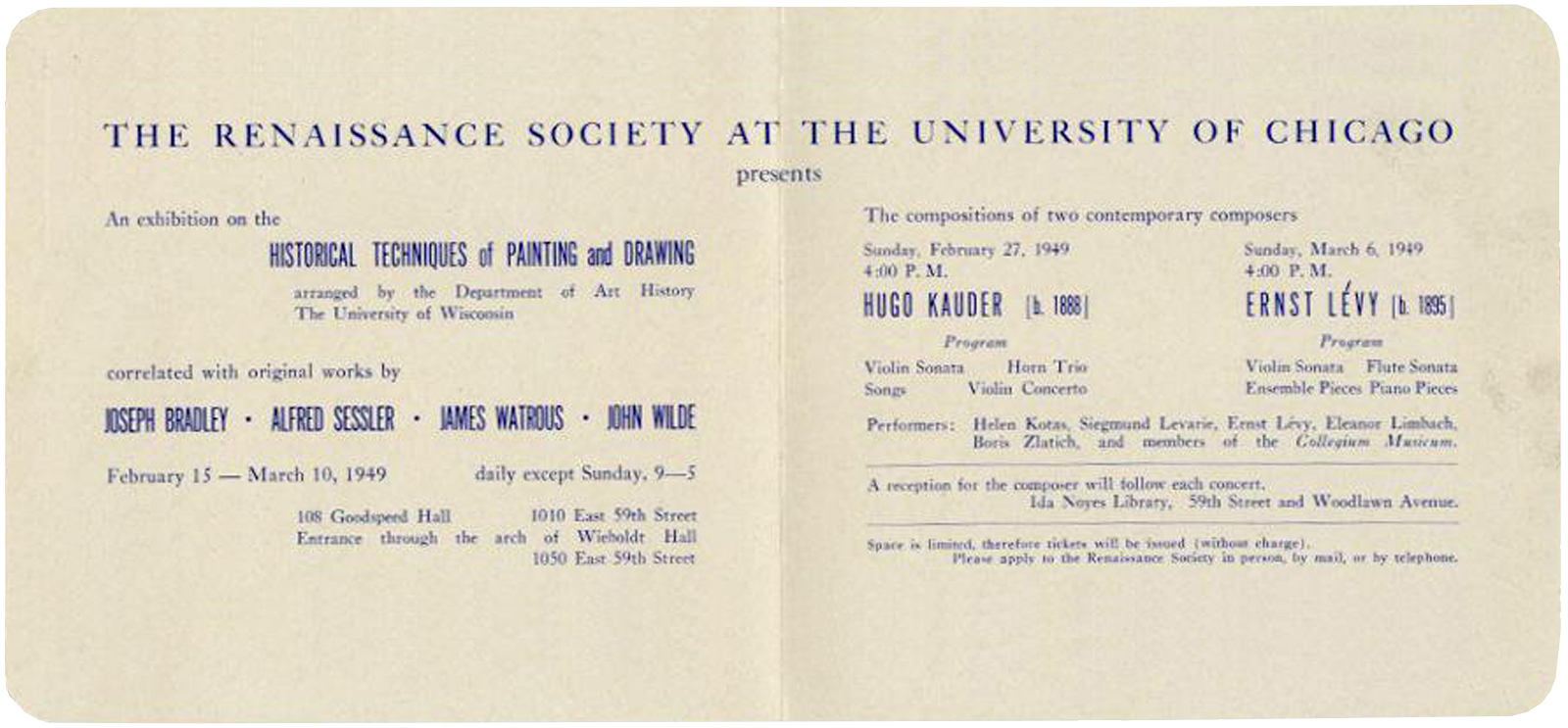

Exhibition and events program from spring 1949. (Courtesy Renaissance Society)

For a century, the Renaissance Society has focused on artists and the ideas that inspire them.

The staff at the Renaissance Society, the independent contemporary art gallery in Cobb Hall that’s celebrating its centennial this fall, knows not every visitor will love every exhibit. And that’s OK—even ideal.

A recent visitor, communications director Anna Searle Jones recalls, told her that the installation he was there to see “’doesn’t do it for me, I’ll admit.” He went on: “‘But I trust the Ren, I like what the Ren does, and I can come and even if I don’t like it, it’s going to make me think about something.’”

Founded by University of Chicago faculty in 1915 as a venue for lectures on art and beauty, the Ren has always strived to make visitors think, says executive director and chief curator Solveig Øvstebø. Each season it produces a series of installations, performances, and other events all designed to spark thought and conversations. The Ren pays to commission and install the art rather than purchase it. “This is a museum and it’s called a museum but it’s not a collection,” she says. “We started out wanting to address ideas and not things.”

The art and ideas were initially fairly traditional, but the Ren’s first director, a founder of the photo-secession movement, “had an agenda to do contemporary art,” says Karen Reimer, the Ren’s registrar and director of publications. Under her leadership, the focus quickly and decisively shifted to the avant-garde. That director, Eva Watson-Schütze, was one of the first to describe the Ren as a laboratory—a place for experimenting, for testing ideas, for pushing boundaries.

Over the past century, many influential artists have been a part of that laboratory, including Henri Mattise, Pablo Picasso, Mies Van Der Rohe, Réné Magritte, Marc Chagall, Jeff Wall, and Felix Gonzalez-Torres. The Ren was the first in the United States to exhibit Alexander Calder’s mobiles and the first Chicago institution to show Jenny Holzer’s work.

Part of what makes the experiments work is the level of support artists receive from the Ren and its staff. Part of Gabriel Sierra’s installation was a title that changed every hour, so Ren employees set alarms in the office and changed the sign outside the gallery at the top of each hour of the show’s two-month run. In 2014 the two-story gallery’s ceiling structure, a steel truss grid that had been in place since 1967, was demolished to complement filmmaker Mathias Poledna’s exhibition, which juxtaposed seemingly found and archival footage with the newly renovated space.

Such accommodations can be made in part because the Ren’s directors over the past century consciously decided to stay small and focused. “It’s considered the natural growth of an institution to get bigger and get your own space, to get your own collections,” says Reimer. But choosing to remain a single-gallery museum means the Ren can put all of its resources behind each exhibit. “I think it really does set the artist free and they do take chances here that they don’t take other places, or aren’t allowed to take other places,” she says.

For the anniversary season, Øvstebø wanted to honor the museum’s unique model. From Chicago-based artist Irena Haiduk’s audio and spatial installation exploring revolution in Serbia to Ian Wilson’s unrecorded discussion positing that visual art doesn’t have to be visual at all, the exhibits and performances aim to present “something looking forward but also something that shows what the Ren is and has been as an institution,” says Øvstebø. The Ren is also hosting a three-day symposium on the future of contemporary art institutions on campus and several readings and events at arts organizations across Chicago.

Opening in November, Let Us Celebrate while Youth Lingers and Ideas Flow, Archives 1915-2015 more explicitly celebrates the Ren’s history with curated art and artifacts from the past 100 years. Based at Midway Studios with pieces in Goodspeed and Wieboldt Halls, both former homes of the Ren, the exhibition will, like the Ren itself, be integrated into campus and, ideally, into campus conversations. Øvstebø and her colleagues see interactions with UChicago scholars and students as crucial to fully exploring the ideas at play in the Ren’s shows. “Contemporary art raises a lot of different questions in our time; sometimes its science and sometimes its philosophy, sometimes its politics,” says Øvstebø. “We want more voices around in that discussion, and we are very well aware that we are in a fantastic place for that.”