(Photography by Anna R. Ressman)

An Oriental Institute Museum exhibit traces the ubiquity of birds in ancient Egyptian culture to geographical accident, avian behavior, and human fascination.

“You have desert, desert, desert—then the Nile Valley, which is very green,” says Rozenn Bailleul-LeSuer, AM’06, a doctoral student in Near Eastern languages and civilizations and guest curator for the Oriental Institute Museum exhibition Between Heaven and Earth: Birds in Ancient Egypt. The lush, marshy Nile valley, she explains, plots out a path for droves of migrating birds each spring and fall. “Avid observers of nature,” the ancient Egyptians were deeply affected by these “spectacular” visitations and showed it in their religious beliefs, philosophy, art, and crafts. Researchers have provisionally identified some 211 different bird species represented in Egyptian artifacts from about 4000 BC through AD 395.

Key figures in the Egyptian pantheon were traditionally depicted as birds, notably the falcon-headed Horus and ibis-headed Thoth. Their worshippers mummified millions of the creatures as offerings, capturing and breeding thousands for the purpose each year, especially after the fall migration coinciding with the Nile flood. Birds’ “ability to fly high in the sky led the ancients to believe that they could join the gods,” Bailleul-LeSuer writes in the exhibition catalog, “and thus act as divine messengers, if not as receptacles of the divine themselves.” Some funerary texts claim that they represent the souls of the dead coming back to Earth, “so it’s actually a conquest of death when the birds come” each migration season.

Hunting, fowling, and breeding birds were important facets of the ancient Egyptian economy. Artists covered temples and tombs with carvings and paintings of both indigenous species (hoopoes, kestrels, grey herons) and migratory ones (quail, storks, house martins, lapwings). Bird motifs graced ordinary household objects, too, such as the exhibition’s ladle and stool legs incorporating duck heads.

In a gallery filled with the recorded songs and calls of native Egyptian species, Between Heaven and Earth displays 35 of the hundreds of avian artifacts in the OI’s collection, many of which have never been shown, as well as a few standout pieces loaned by the Art Institute of Chicago, the Brooklyn Museum, and the Field Museum of Natural History. The exhibit, which runs through July 28, 2013, concludes with a look at the state of today’s avian Egyptian population. Environmental changes—more cities, more people, the damming of the Nile—have proven less hospitable to some birds than others. Without quick interventions, writes Field Museum research associate Sherif Baha el-Din in the exhibition catalog, “the more ecologically sensitive and space demanding species ... will join other memories from the past.”

In Chicago, also built on wetlands and lying beneath a major migration path, Bailleul-LeSuer keeps her eyes and ears open. “If you pay attention to movement,” she says, “you’ll know they’ve arrived and are all around you.” Growing up in Brittany, France, where her parents were bakers, she exulted in observing songbirds like robins, blue tits, and finches while making bread deliveries to neighboring farms. In graduate school at the University of Vermont, she volunteered at raptor rehabilitation centers, drawn especially to the owls there. Her greatest hope for the exhibition is that visitors will leave, like the ancient Egyptians, alert to the chirps and rustles that surround them.

“Stop looking at all this electronic stuff,” she urges. “You’ll see little wrens, and right now kinglets are migrating” through Chicago. “Kinglets are always on a mission: They’re looking for bugs. They go from branch to branch and ... eventually get closer to you and say, ‘I don’t like you, really,’ and go further. But you got to see them with no binos, no nothing. That makes my day.” Behind the Museum of Science and Industry in Jackson Park, she says, 40 or 50 species are in residence this fall, including many warblers. Bailleul-LeSuer keeps track of her finds, but isn’t a competitive birder. “Anything I see, even a sparrow, I’m excited. I’m not demanding when it comes to birds. Their behavior, when you pay attention, is wonderful—any bird.” On the evidence of Between Heaven and Earth, the ancient Egyptians agreed.

The scribes who devised the Egyptian writing system, the exhibition catalog notes, “drew their inspiration heavily from their surroundings and from the natural world.” Sixty-five oft-used hieroglyphs represent birds, from falcons to quail chicks to owls. This three-dimensional limestone carving, which may have been a model for a sculptors’ workshop, depicts the head of the owl hieroglyph representing the letter M (above). Egyptian art shows most creatures, including humans, in profile, Bailleul-LeSuer says, but the owl is characteristically seen face forward. The sculpture’s intricate details identify it as a barn owl: the heart-shaped face, delicate feathers around its “nose” and beak, and speckled band above the deeply carved eyes.

Carved of serpentine, this falcon representing the god Horus dates roughly from 722 to 525 BC. Nearly two feet tall, it has a modern metal cap over its beak and—not seen in this view—a circular channel drilled from beak to crown and from crown to tail. According to OI research associate Emily Teeter, PhD’90, such interior channels are seen in similar statues used in temples as auditory or voice oracles, through which an unseen priest could speak to a petitioner. However, all other known examples date to at least three centuries later than this object. “The hollowing out of the statue,” writes Teeter, may “reflect its reuse as a voice oracle centuries after it was carved.”

Ancient Egyptians believed that we have different components to our being. The ba, our power to move, appears in iconography as a bird with a human head. When a person died, his or her ba lived on, leaving the tomb during the day and reuniting with the corpse in the netherworld at night. Mummies have masks in part, Bailleul-LeSuer explains, so the ba can recognize whom it should go back to. Statuettes like this one, found in Dendera, are seen in funerary assemblages and in tombs, perched atop the coffin, beginning around 1500 BC. Like most ba birds, this is a falcon, identifiable by its long wings that meet the tail.

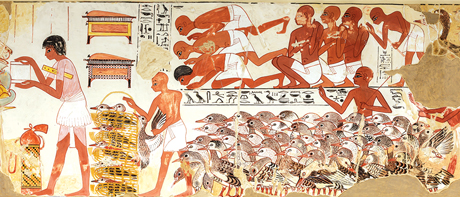

Nina de Garis Davies and her husband Norman copied 170 tomb paintings of astonishing vibrancy and accuracy for the Metropolitan Museum of Art from 1908 to 1938. After making a pencil tracing of the original, Davies would transfer it to the painting surface using graphite paper. Painting by eye in egg tempera, she applied color in the same sequence as the original painter and drew in the cracks left by time. In her facsimile of a bird-hunting scene from the tomb-chapel of Nebamun, several species of birds appear: In the cat’s clutches alone are a wagtail (in its hind claws), a pintail duck, and a second songbird, possibly a shrike. Here, Nebamun’s herders present him with geese from his aviaries while a scribe, far left, keeps count.

This duck-shaped stone jar from the predynastic period, about 5,000 years old, is one of the exhibition’s oldest artifacts and perhaps the most winning. Bailleul-LeSuer says the jar’s red breccia is an extremely hard stone that could only have been carved by a master craftsman. The naturalist in her delights in the duck’s slightly raised tail and extended neck, suggesting it is midswim, and she notes the differentiation of the upper and lower mandibles. Scholars speculate the jar might have held ointments or goose fat in a household or had a funerary use. Most similar specimens are considerably smaller—“this is a very special little guy,” says Bailleul-LeSuer.

While few misdeeds raise a modern antiquities conservator’s ire more than unwrapping a mummy, opening animal mummies was common practice until just a few decades ago. The exquisitely wrapped but exceedingly fragile mummy (top)—happily never unwound—was excavated at Abydos, home to many temples. The embalmer painstakingly layered thin strips of brown and black linen in a chevron pattern, stitching them together in the back. Researchers had speculated the bundle contained an ibis mummy, but CT scanning revealed only reeds, feathers, and a few long bones held together in a bird shape.