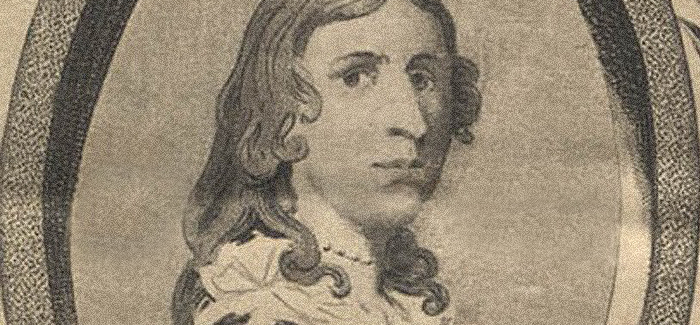

Revolutionary War hero Deborah Sampson. {{PD-old-100}}

Anne Ford, AM’99, questioned her own academic ability—then she started asking questions of others.

It’s said that nothing makes us lonelier than our secrets. For a while in my early 20s, my secret was this: I didn’t belong at the University of Chicago. Though I’d been accepted to the AM program at the Divinity School, I felt I was missing some indefinable but important attribute that, undergraduate performance and professor recommendations aside, would truly qualify me to be there. Its lack spooked me at every moment, whether I was listening to my fellow students discussing Nietzsche and Hegel with aggressive ease, anxiously looking up the definitions of “apophatic” and “hermeneutic,” or being advised by a professor, “You should be hitting the ground running.”

If that sounds like garden-variety impostor syndrome, it was, but only in part. The truth is, I simply wasn’t suited to graduate school, having done well academically all my life without feeling much passion for my studies. Because I was a good student, that lack of genuine scholarly commitment escaped my undergraduate professors, who regularly returned with As the papers I seldom wrote earlier than the night before they were due. (Dear All My Teachers Ever: I’m really sorry.)

During my undergraduate years at a different school, only one professor ever caught on that I was more or less phoning it in: a visiting prof with whom I did an independent study on medieval literature. It came back with the puzzling grade of “A ... for now” and a note in her small, stylish handwriting: “You are smarter than this paper.”

Little did she know, I thought, that I wasn’t smart at all—not in the way that my professors and fellow students seemed to be. No matter the class I took, everyone seemed to be constructing, debating, and dismantling concepts. Whatever the subject matter, the abstract approach seemed to be the ideal one. I understood that. But it just wasn’t ... fun.

Surrounded by scholars, I was more like a newborn baby: fascinated most by very close, very specific things. But instead of the black-and-white mobiles that babies love, I seemed to be obsessed with people—what they said, how they moved, what they thereby revealed without realizing it.

Take my calculus professor, a small, moist man in oversized glasses. As an adjunct, he dribbled onto campus for only a few hours a week and spent most of that time with his back to the class, scrawling functions on the whiteboard—except for the day when he revealed, for reasons I can’t remember, that his wife called him only by his last name.

A tiny, totally irrelevant fact. But for the first time all term, my ears perked up. Really? Huh. Why? And why would he tell us? I never tried to find out more. Just witnessing that small moment of revelation made me happy. It was like a present, and I immediately liked him a little better for giving it to us.

In the margins of my lecture notes, I started habitually scribbling down all the little asides my professors made, along with any other personal details that caught my attention. In Christian History, I learned about Arianism and the Apostles’ Creed, and that my professor’s poker face never ever broke, not even when he asked us if we were under the impression that the Bible had fallen from the sky in a red leatherette edition with a zipper. In East Asian Studies, I noted that Lao-tzu was likely a mythical figure, but also that our Ohio-born-and-bred teacher’s accent made “pleasure” rhyme with “faze her.”

When it came time to decide what to do after graduation, I gave in to the pressure of my academic past and entered the Divinity School, thinking I’d get a doctorate and become a professor like the ones I loved observing. Though my surroundings changed, my proclivities didn’t. When I took a religion and literature class taught by Wendy Doniger and David Grene—two of the finest minds any student could hope to encounter—it wasn’t the Christian themes of Measure for Measure that drew me in, but rather the way that I always ran into the professors walking to class together. What a tender scene: Doniger patiently helping the elderly Grene as he slowly, painfully made his way up the steps. And what a blustery one: Grene thrusting a wild index finger at us as he raged that we were forbidden from writing papers longer than ten pages, “so help you God!” Those moments made it into my margins too.

By the second and final year of my master’s program, I had resigned myself to the fact that I wasn’t an academic. So instead of choosing my courses based on a doctoral future I now realized I’d never have, I just registered for what looked interesting. What looked interesting was a series of courses on women and religion in early American history, taught by Catherine Brekus.

Kind, down-to-earth Professor Brekus didn’t supply me with many quirks to document. Instead, under her tutelage, I wrote the paper that in retrospect represented the first step toward commodifying my old, odd habit. It was about Deborah Sampson, the Colonial-era indentured servant who disguised herself as a man in order to fight in the Revolutionary War. In my paper, I fulfilled the assignment by using her example to construct some argument I can’t remember about the church, gender, and the military.

But along the way, I explored for the first time what really fascinated me: in this case, the personal and historical details that helped Sampson succeed in her scheme. For one thing, she was 5 feet 7 inches, very tall for a woman then. For another, in those days puberty hit later in life, so the fact that she never shaved wasn’t suspicious. Then, too, her eventual assignment as waiter to a general afforded her more personal privacy than the average soldier.

Still, it amazed me that Sampson succeeded in her disguise. How lonely she must have been, and how afraid. I was in disguise too, of course. Sampson was finally unmasked, after 17 months of service, by a fever and a subsequent doctor’s examination. My unmasking took much longer, and it didn’t happen all at once.

Instead, after earning my AM, I left the University, acquired a bill-paying job, and on my own time began tiptoeing further into the realm of what fascinated me. First I found Studs Terkel’s (PhB’32, JD’34) Working: People Talk about What They Do All Day and How They Feel about What They Do, a collection of interviews with waitresses, supermarket cashiers, bank tellers, doormen, cab drivers, and dozens of other people who spoke frankly about their work and their lives. Since then, I’ve come across many other projects with the same approach (NPR’s StoryCorps radio series, John Bowe’s oral history collections Gig and Us, and Stephen Bloom’s The Oxford Project, to name some of the best).

But it was Working that first made me realize: learning about other people doesn’t require spying and sneaking. On the contrary, almost all of us are delighted to talk about ourselves openly and genuinely—if someone will only ask.

So I started to ask. Deborah Sampson was long dead, but there was an entire world of other people with stories just as absorbing. Some of them wanted to tell me those stories; some periodicals wanted to publish them. And to my amazement, I slowly built up a career as a freelance writer and oral historian. Many years after leaving academia, noticing and documenting other people is my full-time job, whether I’m interviewing a burlesque performer for the Chicago Reader or a fried-chicken magnate for the Chicago Tribune. And I don’t write in the margins anymore.

Anne Ford, AM’99, is a writer in Evanston, Illinois. Her oral-history series, Chicagoans, has appeared in the Chicago Reader since 2010; a companion film series can be seen at www.thechicagoans.tv.