Tara Zahra, the Homer J. Livingston Professor in the Department of History and the College. (Photography by John Zich)

In her histories of globalism, migration, families, and children, Tara Zahra reveals the fine cracks in foundational stories.

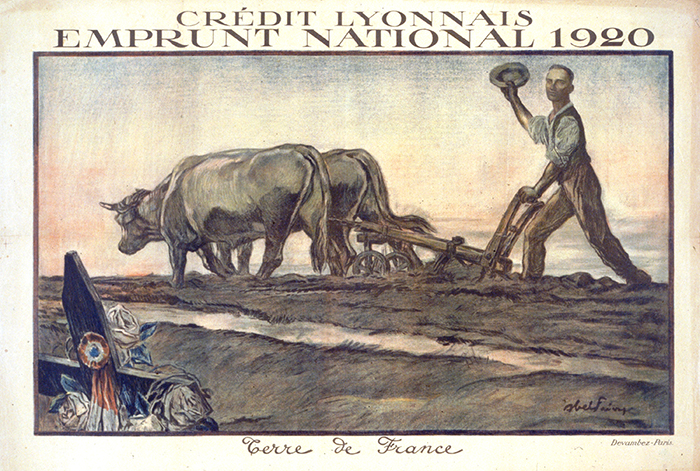

In 2016 Tara Zahra, a historian of modern Europe, was diving into research for a book about anti-globalism between the world wars. She hoped to discover why, from 1918 to 1939, governments and ordinary people worldwide stepped back from international engagement, whether that meant calling for limits on migration, questioning treaties and trade deals, or growing food locally to cut reliance on imports.

As Zahra worked, the daily news headlines gave her a feeling of déjà vu. In 2016 British voters spurned integration and opted to leave the European Union. Donald Trump won the US presidency, vowing to rip up free trade agreements and build a wall along the border with Mexico. Right-wing nationalist movements gained ground in East Central Europe, where Zahra, the Homer J. Livingston Professor in the Department of History and the College, centers her research. On the left, critics in many countries denounced the social inequalities that globalization created and fed, as well as its negative environmental impacts.

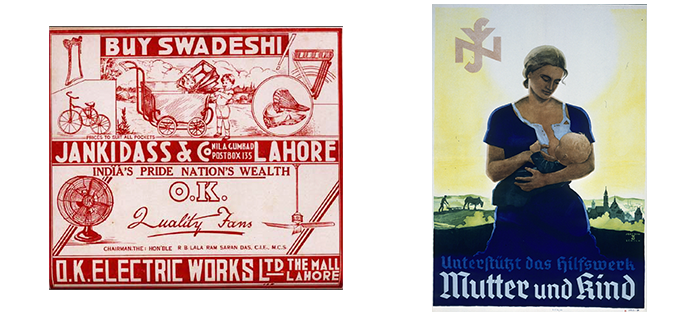

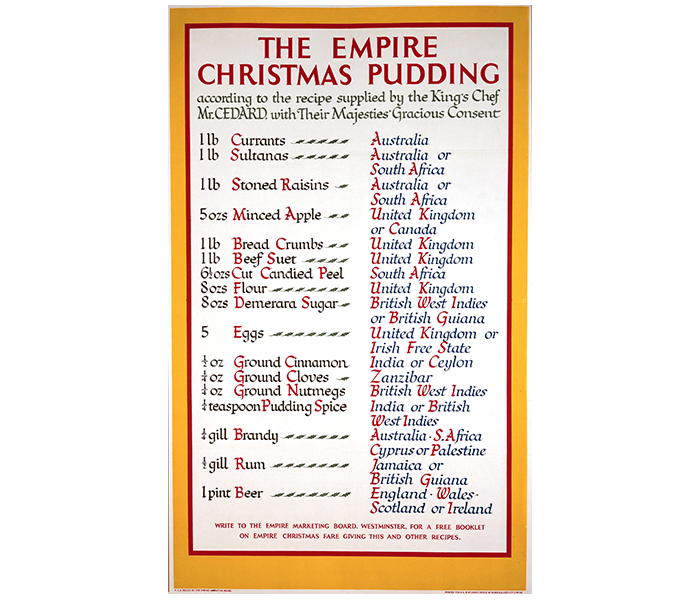

Drawing lessons from current events, Zahra’s newly published book Against the World: Anti-Globalism and Mass Politics Between the World Wars (W. W. Norton, 2023) builds its case from Zahra’s archival research in seven countries. Using those materials, she shows how anxieties about the perceived and real consequences of globalization fueled wide-ranging efforts to change or slow cross-border flows of people, goods, and capital. The cast of characters includes Benito Mussolini, Mahatma Gandhi, and other famous nationalists, as well as people usually at the margins of power, including migrant women.

Across time and space, one of the most striking qualities of anti-globalism has been its “political promiscuity,” Zahra writes. Although such movements are most often associated with European fascism, during the 1930s they grew around the world “on the right and the left, in the most resilient democracies, and in the parliaments of small states as well as those of great powers.”

People with these concerns didn’t use the term globalization, which first became a buzzword in the 1990s. Instead, they talked about freedom and sovereignty as better than dependency on foreign trade and fickle financial markets. Countries that lost the First World War saw the Covenant of the League of Nations and the Treaty of Versailles, both signed in 1919, as deeply unfair. Many saw national self-sufficiency, or autarky, as the way forward. Their arguments still resonate today.

Against the World shows how anti-global movements in divergent locations shared similar aims and strategies. During the Great Depression, Henry Ford required auto workers in Iron Mountain, Michigan, to cultivate vegetable gardens after putting in their hours on the factory floor. Around the same time, the Italian Fascist government created 160 “new towns” where rural settlers would grow wheat for pasta and bread to feed the nation. A continent away, the Swadeshi movement exhorted Indians—especially women—to boycott foreign goods and spin their own cloth rather than import it from England. And in Germany, a 1918 pamphlet called Jedermann Selbstversorger! (Everyone a Self-Provider!) urged citizens to trade their meat-based diet for fruits and vegetables grown in local gardens. Translated into several languages, the treatise influenced Austrian and Zionist settlement movements during the interwar period.

A belief in self-help and disdain for the dole motivated Henry Ford’s gardening scheme. “The man too lazy to work in a garden during his leisure time does not deserve a job,” he wrote in a 1931 directive to Ford employees. Meanwhile, Zahra found, the push for food self-sufficiency in Central Europe had its roots in the searing experience of hunger. On the eve of World War I, Germany relied on imports for about one-third of its food supply. The British exploited that vulnerability by launching a naval blockade that kept food and weapons from reaching the Central powers—and by the war’s end, hundreds of thousands of civilians had died of starvation.

Many Central Europeans blamed a reliance on imports for these deaths and for their countries’ devastating military defeat. “Dwindling food supplies corroded citizens’ faith in the fairness and reliability of markets and the global economy,” Zahra writes. In the decades that followed, people of diverse political persuasions would continue to mobilize against global economic arrangements they deemed unfair. By the 1980s and ’90s, striking miners in Margaret Thatcher’s Britain, street protesters in Seattle, and others worldwide would call attention to the fact that, as Zahra concludes, “tensions between globalization, equality, and democracy remained painfully unresolved.”

Against the World, Zahra’s fifth book, draws on her skill as a transnational and comparative historian. That quality, among others, has earned her the admiration of colleagues including Leora Auslander, the Arthur and Joann Rasmussen Professor in Western Civilization in the College and professor of European social history. “It’s very unusual for a historian to simultaneously range across continents, languages, and historiographies, while at the same time getting her hands dirty, so to speak, in the archives,” Auslander says. When Zahra was named a MacArthur Fellow in 2014, the foundation praised her first two books for combining “broad sociohistorical analysis with extensive archival work across a wide range of locales” and “painting a more integrative picture of twentieth-century European history.” Zahra, 38 at the time, said winning the no-strings-attached fellowship “felt like being struck by lightning, but a particularly good kind of lightning.”

Zahra has logged countless hours in archives abroad and uses German, Czech, French, Italian, and Polish in her research. Yet, early on, she did not expect to have an international academic career. Zahra grew up in rural Pennsylvania, where her parents run a mom-and-pop butcher shop in the Poconos. Until her teens, she hoped and trained to become a professional ballet dancer, but after weighing her prospects, she chose instead to attend Swarthmore College. The first-generation student took a German history course freshman year with a professor named Pieter Judson, who scrawled the words “Please be a history major” on her first paper.

By senior year, fired up by Judson’s seminar on fascism, Zahra decided to go to graduate school and study Central European history. “I felt passionate about history in a way that I hadn’t loved anything since dance,” she says. The summer after college, she traveled to Vienna to study German and help Judson with a research project about nationalism in the Habsburg Empire. It was her first trip to the region. She also worked briefly as a journalist with the American Prospect, a progressive policy magazine, before heading to the University of Michigan to begin her graduate work.

History as an academic discipline values originality and rewards scholars who ask and answer compelling questions, especially when they dig up new or neglected sources and use them to challenge conventional wisdom. Those qualities in Zahra’s work have propelled her “meteoric” career, says Auslander. “She has an extremely good eye for the questions that matter, that are answerable with historical sources and methodology, and fit into conversations that historians have,” adds Auslander. “That’s been true of all of her books, in different ways.”

Based on her dissertation, Zahra’s award-winning first book, Kidnapped Souls: National Indifference and the Battle for Children in the Bohemian Lands, 1900–1948 (Cornell University Press, 2008), was published the year after she joined the UChicago faculty. It focuses on competing efforts by German and Czech nationalists to establish schools and educate children in the former Austrian Empire. As the region’s political boundaries shifted, both sides fought bitterly to recruit children and parents who would identify as future members of the Czech or German national community.

But the twist, Zahra found, “is that a lot of ordinary people were quite indifferent to nationalism. Many people in the region were bilingual. They changed nationalities, they intermarried, they were very pragmatic. There was a gap, and in a way, the indifference of ordinary people to nationalism radicalized nationalism further.”

That novel interpretation “calls into question everything we know about Eastern Europe,” says Judson, who is now a professor of history at the European University Institute near Florence. Zahra does not take anything for granted, “and that’s completely annoying when you’re her professor,” he says, laughing—but it’s one of her greatest strengths. “The thing that makes her distinctive as a historian is that she takes categories we are all quite comfortable with and shows us why we should be uncomfortable with them. ... And if we explore these contradictions more, we’ll see what’s actually going on in the real world.”

In The Lost Children: Reconstructing Europe’s Families After World War II (Harvard University Press, 2011), Zahra movingly dissects the complicated categories of family and nation. “During and after the Second World War,” she writes, “an unprecedented number of children were separated from their parents due to emigration, deportation, forced labor, ethnic cleansing, or murder.” In Europe some 13 million children lost one or both of their parents. Believing that separation caused psychic trauma, humanitarian agencies and governments worked to repatriate “lost” children in the postwar years and, when possible, to reunite them with their parents. Many such parties viewed Nazism and Soviet Communism as evil ideologies that sought to undermine family sovereignty and the private sphere. By reconstructing families, Zahra argues, policy makers hoped to strengthen democracy.

Yet Zahra also finds stories that complicate this narrative. “The golden formula of return to nation and family posed serious problems for surviving Jewish youth,” she writes in The Lost Children. Orphaned by the Holocaust, many Jewish children endured the war in hiding or exile. Those who had been sheltered by religious institutions or adopted by non-Jewish families could not easily be reunited with surviving members of their birth families. Jews of any age who attempted to return home often encountered persistent anti-Semitism.

And, as Zahra notes, anti-Semitism was not confined to Nazi Germany or Eastern Europe. In liberated France, for example, the postwar government issued a memo in October 1945 calling for the deportation of German-Jewish refugees who remained on French soil, since such individuals were “of no economic or demographic interest.” War-ravaged countries such as France and Czechoslovakia wanted to rebuild, but they saw a young and nationally homogenous (or at least “assimilable”) population as the most desirable asset to this process.

These days Zahra’s work and life keep her anchored in Chicago, but with an outward gaze. In 2022 she was appointed the Roman Family Director of the University’s Neubauer Collegium for Culture and Society. Established in 2012, the Collegium supports humanistic research by faculty-led teams, a visiting fellows program, and an art gallery. Its assets include a full-time professional staff and a generous budget to fund collaborative projects involving scholars from every corner of the University, Zahra says.

Housed in a graciously renovated neo-Gothic building at the corner of 57th Street and Woodlawn (the former home of the Meadville Theological School), the Collegium offers space for offices, meetings, and events.

Seated by a window in the Collegium’s light-filled library, Zahra talks about how her research and her goals as director align. “I write histories that try to speak to broader audiences, even though that’s easier said than done in practice,” she says. The Collegium can play a similar role, she believes, by expanding programming and collaborations in the arts, building links with institutions in the city of Chicago, and funding research that informs contemporary debates and helps solve real-world problems. “The people involved in our projects are not only academics; we have practitioners, artists, policy makers,” Zahra says. “I’m really excited, particularly at this phase of my career, to have this chance to help the research that is produced on this campus to have an effect in the world.”

For years Zahra has sought to connect her scholarship to issues and people beyond the academy, a practice that coincides with her winning the MacArthur award. “More important than the money was the feeling that I had a suit of armor, a little bit,” she says. “I think it changed my relationship to my work [and] gave me the courage to do more risky things, to venture a bit, and to believe in myself.”

Zahra’s third book, The Great Departure: Mass Migration from Eastern Europe and the Making of the Free World (W. W. Norton, 2016), focuses on the period from 1846 to 1940 when more than 50 million Europeans immigrated to the Americas. The research gave Zahra a jumping-off point to discuss the complicated history of immigration in the media. She wrote pieces for Foreign Affairs and the Daily Beast and published a 2015 New York Times op-ed that challenged the myth of America as the promised land.

Noting that 30 to 40 percent of European immigrants before the First World War ultimately returned home, Zahra argued that “today’s migrants are not so different from their predecessors.” Many hope to return to their countries of origin someday, she wrote, “if only they could do so securely. But in a world in which visas are lottery prizes, and refugees die in trucks or find themselves trapped in stateless purgatory, it is not so easy to come and go freely.”

Objects of War: The Material Culture of Conflict and Displacement (Cornell, 2018), which Zahra and Auslander coedited, grew out of two Collegium-funded workshops. The book examines personal possessions that people carried with them as they fled war and persecution in 19th- and 20th-century Europe, drawing a parallel to the mobile phones and toys carried by Syrian refugees in 2015 as they escaped conflict in their homeland. Abandoned suitcases, shoes, and eyeglasses are a poignant fixture in Holocaust museums around the world. The goal of such displays, Zahra and Auslander write, is to “remind us of how people in desperate circumstances rely on familiar things in their efforts to retain memories and maintain a sense of self.”

Scholarly histories like The Great Departure and Against the World are unlikely to become bestsellers, but Alane Salierno Mason, vice president and executive editor at W. W. Norton, bets they will find an audience among “smart readers who want to be smarter.” She lauds Zahra’s ability to combine “an extraordinary analytical mind” with narrative sensibility, and sees her as part of a growing generation of respected women historians whom Norton publishes that includes Mary Beard, Jill Lepore, Mae Ngai, and others.

Even so, history remains a field dominated by men. Beard, a renowned scholar of Ancient Rome, has complained that “big books by blokes about battles” still top the bestseller lists in Britain because readers place greater trust in male authors to tackle weighty topics like war and economic policy. This is despite the fact that universities place more value than ever before on fields such as the history of gender, sexuality, race, diaspora, and indigeneity. “There’s also been a huge increase in the number of women writing about all topics of history,” Zahra says. But “I would say we still have quite a bit of progress to make.” Just six of the 24 full professors in UChicago’s history department are women, she notes, and “women and minorities are still dramatically underrepresented at the highest ranks of academic institutions.”

“I think we still have the perception of intellectuals—and public intellectuals—as male,” says Zahra, who is the first woman to lead the Collegium since its 2012 founding. “I was surprised to be asked to take this role, but I’m also really happy to have the opportunity to affect people’s own ideas of what intellectuals look like.”

For Zahra, life as an intellectual includes continuing to dance, teach, write, and recharge. She takes twice-weekly ballet classes and will coteach a class on dance as history next fall through the University’s Gray Center for Arts and Inquiry. She and Judson have coauthored The Great War and the Transformation of Habsburg Central Europe (Oxford University Press, forthcoming), a social history that shows how ordinary people in Austria-Hungary both suffered and exerted agency during World War I. Zahra and her husband, UChicago physics professor William Irvine, like to rock climb and hike with their four-year-old daughter, Eloisa. The mountain town of L’Aquila in central Italy, where Irvine grew up, has become a favorite summer destination.

Zahra dedicated Against the World to her daughter with “love and hope for a better future.” But as the book went to press, Russia’s war with Ukraine raged on, the climate crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic tested international relations, and a political party with fascist and anti-immigrant roots elected Italy’s first woman prime minister—proof that the world’s anti-global moment is not over yet.

Still, Zahra is cautiously optimistic. “One of the lessons of history is that nothing that seems forever actually is,” she says. “My greatest hope would be that this is a transformative moment in which a vision of globalization that is more responsive to democratic politics might come into being.” Global interconnections won’t stop, but they can be reorganized “in ways that don’t continue to exacerbate extreme inequality domestically or internationally,” Zahra says.

“Moments of huge discontent can also produce change.”

Elizabeth Station is a writer in Evanston, Illinois.