Elizabeth Gordon and Frank Lloyd Wright at Taliesin West in Scottsdale, Arizona. Gordon’s attacks on International Style attracted criticism but earned her a lifelong friend in Wright. (Maynard L. Parker, photographer. Courtesy of The Huntington Library, San Marino, California.)

She made enemies with her attacks on International Style–but a powerful friend in Frank Lloyd Wright.

Two ways of life stretch before us. One leads to the richness of variety, to comfort and beauty. The other, the one we want to fully expose to you, retreats to poverty and unlivability,” declared House Beautiful editor in chief Elizabeth Gordon, PhB’27, in a controversial 1953 essay, “The Threat to the Next America.”

The road to perdition? International Style architecture. For Gordon, an Indiana native who for more than two decades brought her vision of good design to America’s middle-class homemakers, the work of architects such as Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Le Corbusier was nothing less than an affront to reason.

Embracing modular forms, mass-produced industrial materials, and flat glass surfaces, the style had emerged in Europe in the 1920s, and by 1932 was being lauded by curators at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. Gordon took a dimmer view, accusing its architects of shunning comfort, convenience, and functionality, all necessities of home life—a stance that “sparked an instant and enduring controversy,” according to Gordon’s biographer Monica Penick, author of Tastemaker: Elizabeth Gordon, “House Beautiful,” and the Postwar American Home (Yale University Press, 2017).

In House Beautiful’s pages, Gordon pulled no punches. “The much-touted all-glass cube of International Style architecture,” she wrote of Mies van der Rohe’s famous Farnsworth House in Plano, Illinois, “is perhaps the most unlivable type of home for man since he descended from the tree and entered a cave. You burn up in the summer and freeze in the winter, because nothing must interfere with the ‘pure’ form of their rectangles—no overhanging roofs to shade you from the sun; the bare minimum of gadgets and possessions so as not to spoil the ‘clean’ look. … No children, no dogs, extremely meager kitchen facilities—nothing human that might disturb the architect’s composition.”

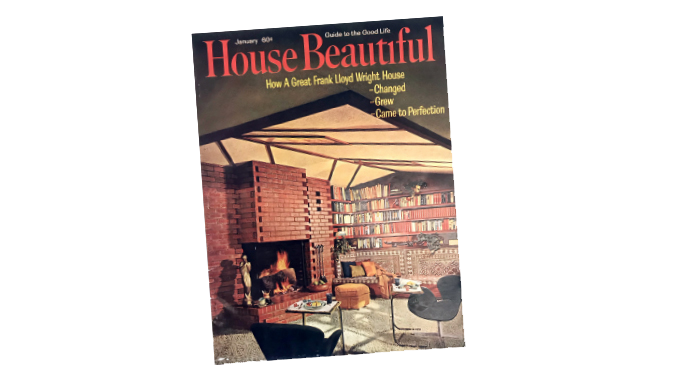

Gordon’s blistering words won her critics and admirers alike, most notably Prairie School pioneer and fellow International Style detractor Frank Lloyd Wright, who wired this response: “Surprised and delighted. Did not know you had it in you. From now on at your service.” That message marked the start of a lifelong collaboration. Calling her office “an extension of Taliesin,” after Wright’s design studio, Gordon would go on to produce two special issues celebrating his work and hire a Taliesin apprentice architect as House Beautiful’s architectural editor.

While the essay brought Wright and Gordon closer, it prompted much criticism. Architect William Wurster, for example, penned a letter of opposition, cosigned by 30 fellow California designers and sent to several architectural magazines and schools. They rejected the suggestion that modern architects were attempting to “undermine American freedom” and “regret[ted] deeply the attack on European art and architecture … [and] the implication that all ‘good’ art has its roots in America and all that is European is subversive, perverted or sick.” Editor Peter Blake at Architectural Forum was particularly incensed and suspected Gordon had cast a die that would end her career. “Here lies House Beautiful,” he wrote, “scared to death by a chromium chair.”

The only child in a devout Methodist family, Gordon developed her critic’s eye—and rebellious streak—early. In an unpublished autobiography, she would deride her cluttered, dusty two-story Carpenter Gothic childhood home in Logansport, Indiana, as “best seen from the outside.” As a young woman, Gordon briefly escaped the small farming town, enrolling at Northwestern University for a single semester before her parents forced her to leave because she attended a school dance.

A year later she enrolled at the University of Chicago—with her mother accompanying her as a campus chaperone. Much to Gordon’s relief, her mother soon began taking classes and was too engrossed to monitor her daughter’s every move. Exulting in her newfound freedom, Gordon threw herself into her studies and joined the Maroon staff, setting the stage for her future career.

After graduating she spent a year teaching high school English in Janesville, Wisconsin, saving enough money to move to New York. In Manhattan she wrote freelance home columns for New York World and the New York Herald Tribune before joining Blaker Advertising Agency, first as a copywriter, then as an account executive. Applying her reporting skills to the growing field of consumer research, Gordon investigated women’s purchasing habits. Her work caught the attention of one of her clients, Good Housekeeping, which hired her to cover building and decorating. Gordon quickly made a name for herself in the field. At age 35, when the editor-in-chief position at House Beautiful opened up, she stepped in.

Gordon transformed the magazine into a powerful vehicle for rallying like-minded designers and bringing their work to the average American consumer. Its broad audience included housewives and design professionals who shared an interest in improving domestic life through architecture, interiors, furnishings, and gardening. Under her leadership, the magazine’s readership exploded from 226,304 in 1940 to nearly a million at her retirement in 1964. As one of only a few women leading a mass-circulated publication, Gordon elevated House Beautiful into a serious architectural and commercial influence.

“I used House Beautiful as a propaganda and teaching tool—to broaden people’s ‘thinking-and-wanting’ apparatus,” Gordon wrote later. That meant introducing everyday homemakers to concepts such as the California ranch house and climate control through green design.

Sporting bold hats and even bolder opinions, Gordon crisscrossed the globe to bring readers what she deemed the best in design. “When she covered a topic, she did it in staggering depth,” Louis Oliver Gropp, a former House Beautiful editor, told the New York Times when Gordon died in 2000. Two special issues introducing traditional minimalist Japanese design to American readers in 1960 reflected five years of research and seven trips to Japan. A later edition dedicated to Scandinavian styles earned her a Finnish knighthood. Her vision of the best in aesthetics and quality focused on craftsmanship and materials, regardless of style or country of origin—a distinction that explains how she could laud, say, the minimalism of Japan while skewering that of the International Style.

Writing at the height of the McCarthy era, Gordon borrowed freely from the rhetoric of the times, assailing the International Style’s brand of minimalism as an insidious influence that threatened American life by spreading “something ... rotten” into our homes. For Gordon, the offending style was “clinical” rather than livable and humanistic, two key qualities she sought in “good” design. While she saw the polarizing essay as part of a larger mission to empower consumers with the knowledge needed to create their own beautiful living spaces, its political overtones clearly reinforced a nativism that had taken root in the country.

In Tastemaker, Penick argues that Gordon’s “motivations—why she worked so vigorously to discredit a small group of modernists—were complex.” They were, Penick believes, driven at least in part by her professional interests. Being “inextricably tied to the consumption-centric business of American design,” the biographer writes, “the International Style’s minimalism and its lack of storage for household goods was actually a ‘threat’ to her own industry and livelihood.”

After leaving her post in 1964, Gordon continued to espouse her views through public lectures and consulting. Though her positions were not universally shared, their influence was indisputable; endorsement letters for Gordon’s honorary membership in the American Institute of Architects noted her years of advocacy and “indefatigable pursuit of good domestic architecture.”

Brooke E. O’Neill, AM’04, is a freelance writer in Chicago.