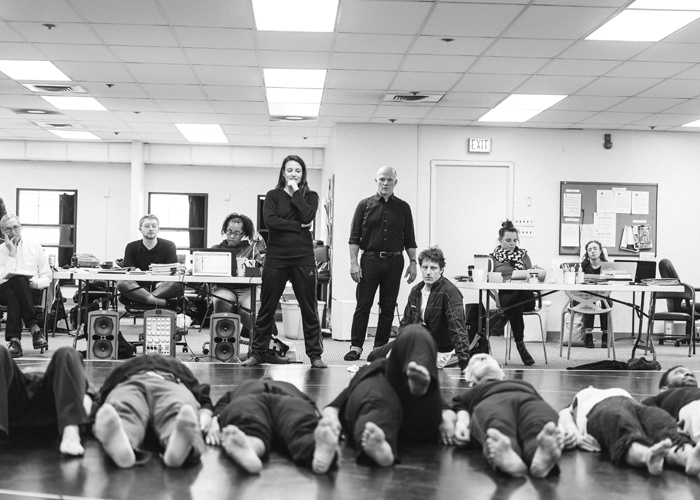

The cast of The Adventures of Augie March. (Photography by Joe Mazza/Brave Lux)

Scenes from a Court Theatre play in the making.

The playwright David Auburn, AB’91, slouches on a couch in director Charles Newell’s office at Court Theatre, trying to decide if there’s a way to get a talking eagle on stage. “I don’t know how to theatricalize it,” Newell says.

It’s July 2017, and the question of how to stage the unstageable is one Auburn and Newell have faced repeatedly since deciding more than a year ago to adapt Saul Bellow’s The Adventures of Augie March. When it opens in May 2019, the play will be the first theatrical adaptation of any work by Bellow, EX’39.

In choosing to stage Augie, the Pulitzer- and Tony-winning playwright didn’t make things easy on himself. The 1953 picaresque novel sprawls over years and countries; there are characters and episodes, “but it doesn’t have a story, strictly speaking,” Auburn says. What holds the book together, as much as anything else, is Bellow’s winding, allusive language. It’s one thing to read long descriptive passages on the page, but another to translate them into dialogue. Among all these untheatrical elements, the eagle stands out as a particular challenge.

In a memorable sequence in the novel, Augie’s lover Thea decides to adopt an eagle, which they name Caligula, and train it to capture giant iguanas in Mexico. When Caligula flops as a hunter, Augie and Thea’s relationship falters too. The eagle scenes are important to Auburn—it’s “such a powerful and complex symbol in the book”—and he’s raised the stakes by adding a scene where the eagle (or at least, an abstracted, metaphorical version of the eagle) speaks to Augie. So, how exactly do you pull that off?

Auburn and Newell consider ideas. Could you do something that suggests an eagle, Newell muses, without actually showing it?

Auburn balks. “I think you really need to commit to the eagle,” he says. Augie talking to the eagle is “the major image of the show.” The scene marks a crucial moment in Augie’s journey: he begins to realize that most people, even the ones who appear absolutely certain about the right way to live, are making it up as they go along.

“I didn’t know you felt so specifically about it,” Newell says.

Auburn is absolutely sure—“Don’t wimp out on the eagle, Charlie,” he teases—but far from having a solution. “Cut to me in a year and a half, wearing a beak.”

Auburn first read The Adventures of Augie March shortly after graduating from UChicago. The references to Hyde Park gave him a sense of kinship with the novel, and he found himself returning to it often. “It was one of those books I kept by my bedside,” he says.

The idea of an adaptation simmered. Auburn loved the motley group of people Augie encounters throughout the book. “The idea of getting some of that incredible variety of humanity onto the stage really appealed to me. I thought, these are great characters, they should be roles that actors can play.”

In 2016 he came back to UChicago to direct Long Day’s Journey into Night at Court and proposed the idea of an Augie March play to Newell, the theater’s Marilyn F. Vitale Artistic Director. Newell was enthusiastic and set to work acquiring the rights to the novel.

As soon as he got the official go-ahead, “I sort of thought, oh Christ, what have I done?” Auburn recalls. The very things he loved about the novel, its capaciousness and meandering structure, made the task of adaptation feel impossible. Halfway through the first draft, he wasn’t sure he could finish the project.

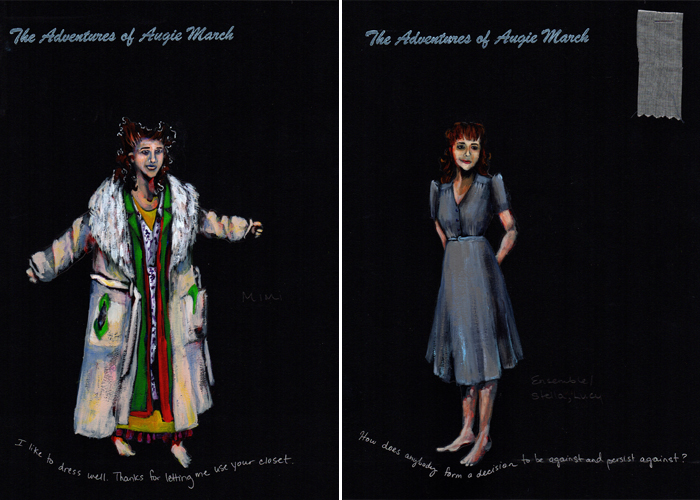

Gradually, though, solutions emerged. Auburn knew early on that most actors in the production would play multiple characters, allowing him to populate the world of the play without hiring a Cats-sized company. And he gave himself permission to be idiosyncratic about which characters and episodes to keep and which to discard. “In a way you could have written a totally different play using different material,” he says. “This is this play, using this material.”

Auburn and Newell found a way to incorporate Bellow’s language—a “giddily heightened, literary, poetic new form of expression,” says Court’s resident dramaturg Nora Titone—when they realized they could treat it like song.

“When we do a musical successfully,” Newell explained in 2016, following a public reading of an early draft of the play, “a character gets to a place where they’re no longer speaking. They have to sing to express the emotion.” The script borrows several rhapsodic monologues from the novel, which serve the same role as songs, revealing things the characters can’t communicate or won’t admit to themselves.

Collaborating with Newell was one of the reasons Auburn wanted to produce Augie at Court. “I knew that I could approach this and there would be no rules, that I could say I want an eagle, and we’d have an eagle.”

By happy coincidence, in 2017, as Auburn was refining his script, the archive of Bellow’s personal papers at the Special Collections Research Center opened. Bellow donated portions of the collection over his 31 years on the UChicago faculty; the rest came after the Nobel laureate’s death in 2005.

For Titone, who got involved in the adaptation in its early stages, it was a dramaturg’s dream. Her job was to delve into the world of the play and give the playwright, cast, and production team historical and biographical information to inform their work.

Studying Bellow’s papers offered Titone insight into his process and intent, and helped her see “how much Chicago, the city, is a force in the production.” Augie is the story of an American immigrant in a city full of them, and that should inform how the production looked and sounded. Titone studied the Studs Terkel Oral History Archive to get a sense of the “kaleidoscope of accents” the actors would need to master.

A team of undergraduate research assistants helped Titone field the other dramaturgical inquiries she received: What was the experience of Russian Jewish immigrants in Chicago? What music would Augie have listened to?

Together, the team unearthed the possible backstories of characters, including Augie’s lecherous neighbor Kreindl, an Austro-Hungarian Jew who fought in World War I. People like Kreindl “were the hardest-hit guys. They were brutalized in the trenches,” Titone says, and the experience would likely have resulted in post-traumatic stress disorder.

She passed their research along to the actor playing Kreindl, who “can take that and do with it what he chooses and build a character internally and privately with that information if he wants,” Titone says. “And that’s the neat thing. You can help activate somebody’s imagination about their art.”

Julia VanArsdale Miller stands in Court’s rehearsal space on Stony Island Avenue. She reaches into a shopping bag and produces a white wireframe puppet prototype. When she slips it on her hand, and adds a fluffy beaked head, it looks unmistakably like a bird.

Nearly two years after Auburn told Newell to “commit to the eagle,” the cast, production staff, and various friends of Court Theatre have gathered for the play’s first rehearsal, which will include a full readthrough of the script.

Before they begin, the set designer and costume designer give brief overviews of their preparations for the production. Then it’s time for Miller, a member of the Chicago-based collective Manual Cinema, to show off plans for the eagle (none of which, happily, involve Auburn with a beak).

Even in its unfinished state, the eagle puppet is lifelike. Miller pulls a cord to make the puppet’s wings flap and manipulates its delicate head. This, she explains, is one of three representations of Caligula that will be included in the production.

Newell’s choice of Manual Cinema to solve the eagle problem is a fitting one. The group, best known for its intricate shadow puppet productions, has a longtime relationship with Court and a track record of “putting things on stage that shouldn’t be on stage,” says Manual Cinema’s co-artistic director Drew Dir, AB’07. The collective has made the humble overhead projector a centerpiece of their work, using a combination of handmade shadow puppets and the silhouetted bodies of actors, to create performances that resemble both plays and animated films.

When they got the script, the Manual Cinema team realized each of the eagle scenes Auburn had written suggested a slightly different approach. The first appearance of Caligula, they concluded, demanded a literal puppet, so the group began studying photos of eagles and videos of the birds in flight.

“The challenge is making the eagle look as powerful and as threatening as they can appear in real life,” Dir says. “If you take off all the feathers of an eagle, they’re dangerously close to looking like a chicken. It’s a really thin line between chicken and eagle.”

But three-dimensional puppetry, the group decided, wouldn’t work for the scenes of Caligula chasing iguanas. Instead, depicting the eagle hunt required an approach more like Manual Cinema’s own work, using shadow puppets and actors to depict the scene in silhouette “as if we were filming a movie of it,” Dir explains.

The third bird scene, in which the eagle speaks to Augie, is still a work in progress at this point. Dir thinks they will use shadow, silhouette, and movement in a way that suggests an eagle, “almost like an animated Rorschach ink painting.” But the details won’t be worked out until they get further into rehearsals.

The stage manager begins the read-through with a cheerful “When you’re ready” to Patrick Mulvey, who will be playing Augie. Early in the reading, Mulvey breaks the tension by accidentally starting a key monologue, which incorporates part of the novel’s famous first sentence—“I am an American, Chicago born”—a line too early. Everyone laughs, and the room relaxes.

The play itself is funny too, and Auburn is especially attentive during the comic moments, noticing which ones are landing. As the reading unspools, his glance moves between the actors and audience. His eyes light on Janis Freedman Bellow, AM’90, PhD’92, who, along with other members of the Bellow family, has come to watch.

When the read-through is finished and the rehearsal room empties out, Newell, Auburn, and the cast pull tables and chairs into a circle and debrief. There is a lot still to do in the four weeks ahead: They haven’t finalized which actors will be playing which combinations of roles. The performers have to learn choreography and shadow puppetry. The three-dimensional eagle puppet needs feathers.

But as he has been from the beginning, Newell appears undaunted. They’ve made an evening of theater from a 600-page novel and eagles from wire and light. What’s one more impossible feat?

The Adventures of Augie March runs through June 9, 2019, at Court Theatre, and an exhibition about the production, featuring materials from the Bellow archives, will be on display at the Special Collections Research Center through August 30, 2019.