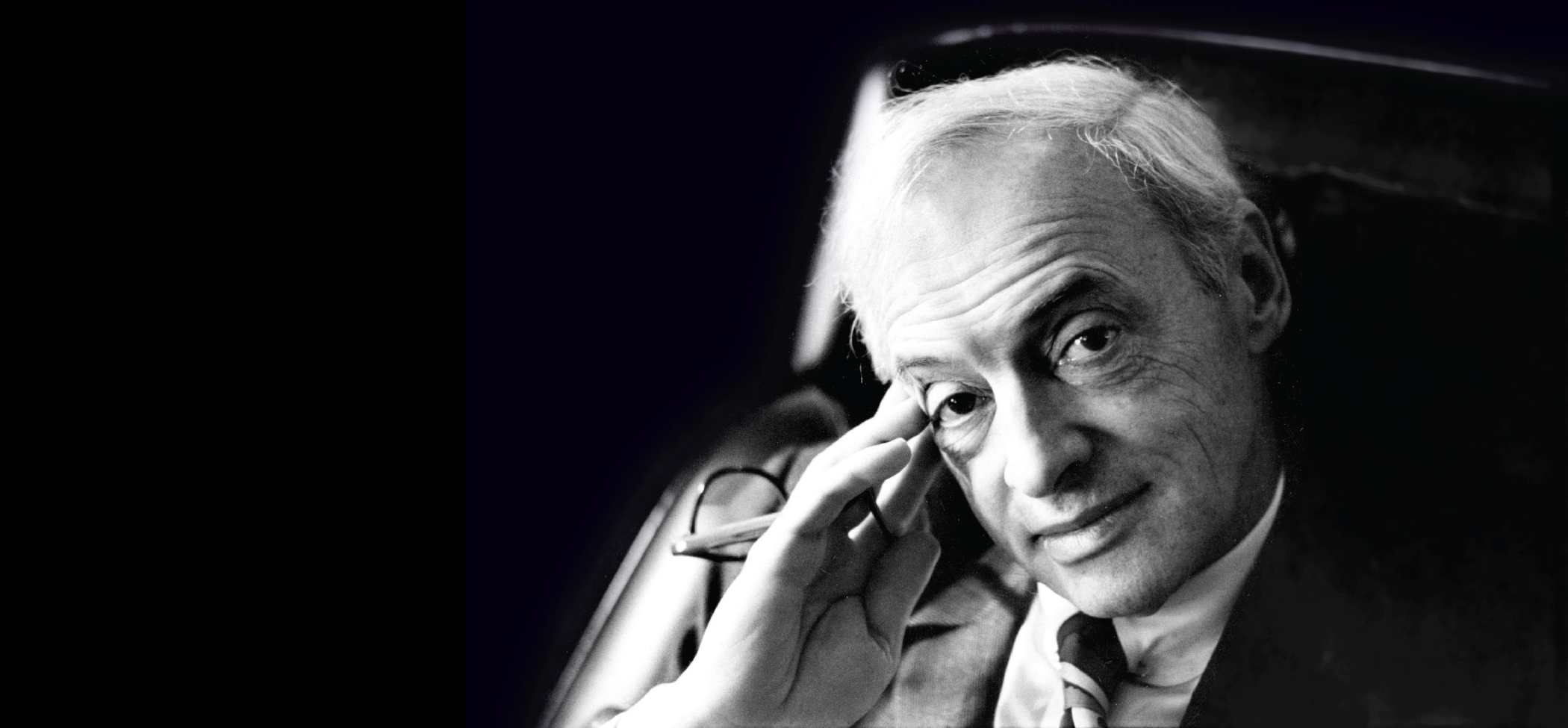

Copyright Jill Krementz/Courtesy University of Chicago Special Collections Research Center

What is it like to sort through the personal papers of one of America’s most celebrated writers?

Saul Bellow, EX’39, wasn’t known for brevity. Perhaps his most famous work, the modern picaresque The Adventures of Augie March (Viking Press, 1953), clocks in at 536 pages; Humboldt’s Gift (Viking Press, 1975), about a rivalrous friendship between two writers, is a hulking 487. Even many of Bellow’s short stories are on the hefty side.

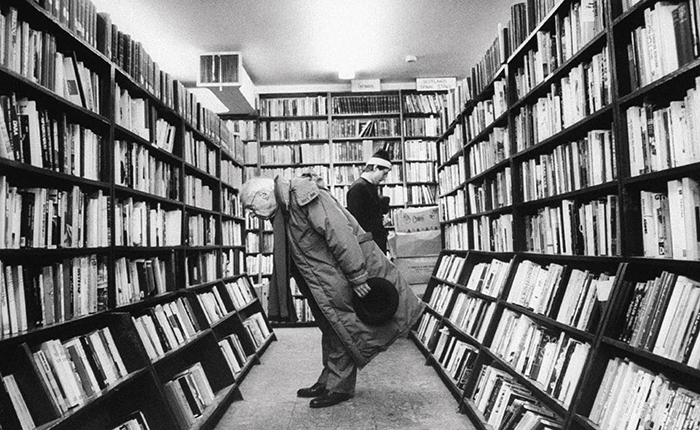

The archive of his personal papers at the University of Chicago Library’s Special Collections Research Center, which opened to researchers in March, is equally voluminous—254 boxes in all. Stacked on top of one another, they would reach four times the height of the Mansueto Library’s dome.

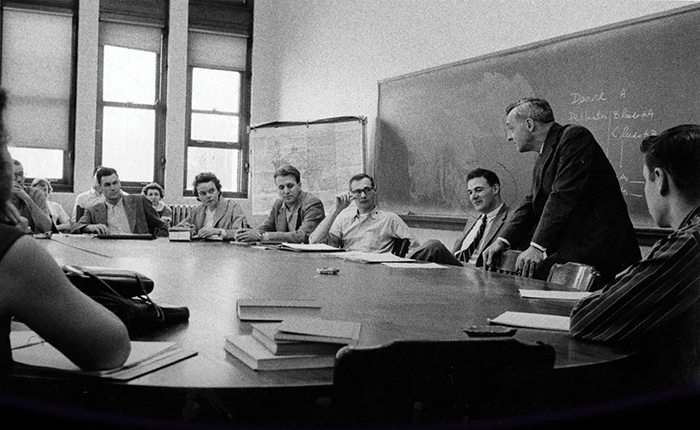

Bellow began donating his papers to the University in bits and pieces during the 31 years he taught on the faculty. In 2006, a year after his death, UChicago acquired his remaining professional papers. It was the right match, Bellow’s biographer Zachary Leader believes, “since he is the great novelist of Chicago.”

At the request of Bellow’s widow, Janis Freedman-Bellow, AM’90, PhD’92, for the next several years only a few scholars who’d received permission from the Bellow estate were allowed to look at them. Eventually, those restrictions expired, and Ashley Gosselar, a processing archivist in Special Collections, got the go-ahead to organize the collection’s drafts, letters, photos, teaching materials, and ephemera for researchers to use. A gift from Robert Nelson, AM’64, and Carolyn Nelson, AM’64, PhD’67, underwrote the cataloging process.

Working on the papers of the 1976 Nobelist was a treat for Gosselar, an English major before she went to library school. “The English lit nerd in me is always thrilled to get to work on the personal papers of a writer and deal with literary manuscripts,” she says. “I think my love of story fed my interest in archives, because that’s what they do. They tell a story of somebody’s life.” Gosselar read Bellow’s novels and previously published letters as well as several biographies of him in preparation for the project.

Faced with a fresh set of papers to catalog, Gosselar does a rough assessment of the materials and develops a broad organizational plan. Then comes the long process of sorting materials into boxes and folders and writing a detailed inventory. In the case of Bellow’s papers, this last stage was especially thorough and took over a year from start to finish. It wasn’t quite all Saul, all the time—Gosselar had a few other projects on the side—but “a large portion of my time was spent with Bellow.”

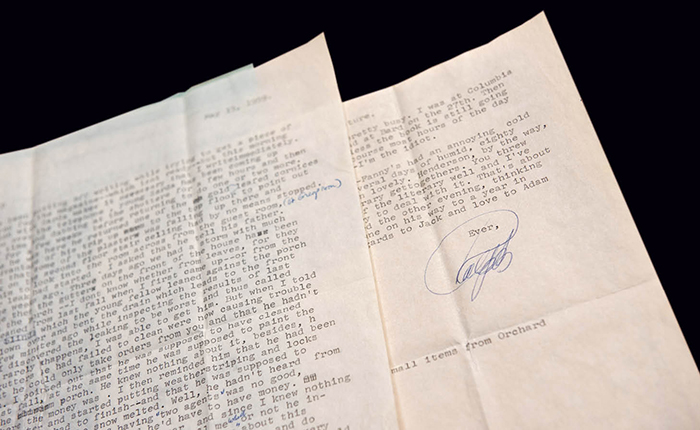

One of Gosselar’s most painstaking tasks was developing a comprehensive list of Bellow’s hundreds of correspondents. It’s a time-intensive step archivists don’t always take, but it made sense given the writer’s community of friends and admirers, which included writers (Don DeLillo, Annie Dillard) and politicians (senators Jacob Javits and Edward Kennedy, President John F. Kennedy)—even Pope John Paul II. Along with the drafts of Bellow’s work, his letters make up what Gosselar calls “the scholarly meat of the collection,” offering “a wonderful window into both his personal life and relationships as well as an excellent picture of his intellectual network.”

In one letter, Bellow commiserated with Philip Roth, AM’55, about critics: “They have none of that ingenuous, possibly childish love of literature you and I have. They take a sort of Roman engineering view of things: grind everything into rubble and build cultural monuments on this foundation from which to fly the bullshit flag.” Kurt Vonnegut, AM’71, jotted a note of appreciation for Bellow’s essay “A Matter of the Soul” on a postcard featuring a photo of the poet Robert Lowell (“It is so resonant for me, a former Chicagoan, born in Indianapolis to cultivated parents whose tastes were European”). Another note contained 80th birthday wishes from John Updike: “The writing part of you seems immune to time.”

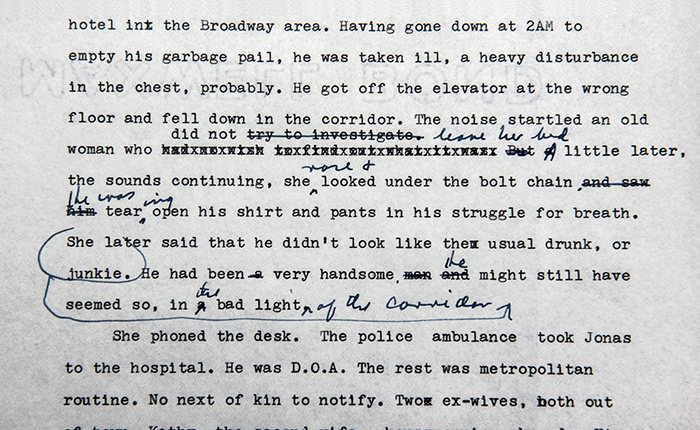

Personal papers arrive in Special Collections in varying states of disarray. Bellow’s were “pretty typical,” Gosselar says—a mixture of tidy and, well, “not so tidy.” His copious drafts were trickiest to organize: “Fragments of drafts had become jumbled and scattered. So I would open up one box and find one piece of a novel draft, and several boxes later find the next few pages.” Piecing them back together looked like “a giant game of Memory,” with stacks of paper spread across a long table.

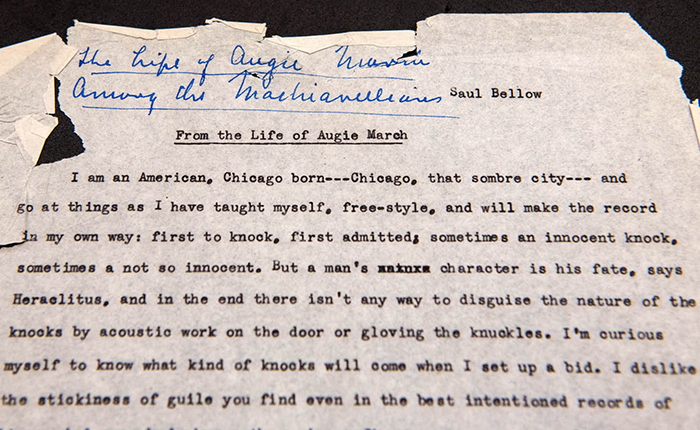

After spending months with Bellow’s drafts, Gosselar came to understand how he worked. “It was clear that he seemed to have an early sense of the story he wanted to tell. But what he revised over and over again was the way in which he was telling it.”

Bellow often began his drafts in longhand, on a notepad or in a notebook, before turning them over to an assistant to type. In subsequent versions he would tweak sentences again and again, shift the perspective from third to first person and back, and tinker with characters’ names (Bellow connoisseurs can debate the significance of the fact that Charlie Citrine in Humboldt’s Gift was originally introduced as Thomas Orlansky, for instance). For Gosselar the paper trail suggested Bellow’s genius wasn’t the result of “direct dictation from the muse. This was labor for sure.”

The reward comes when she sees researchers putting the archives to use. For the Bellow collection, that gratification was almost instant. “As soon as the guide went online and before we had even had a chance to publicize that, we had people in the reading room using it and requesting boxes,” Gosselar says. A sizeable audience of Bellow scholars and fans, it seems, had been waiting hungrily.

For Gosselar, the feeling is different. When she finishes work on the personal papers of someone like Bellow who’s no longer alive, she is “always a little bit sad that I will never meet them because I feel that I know them so well.” Still, the intimacy that emerges between archivist and subject—knowing their handwriting, work habits, daily concerns—lives on for new generations of Bellow scholars and readers.