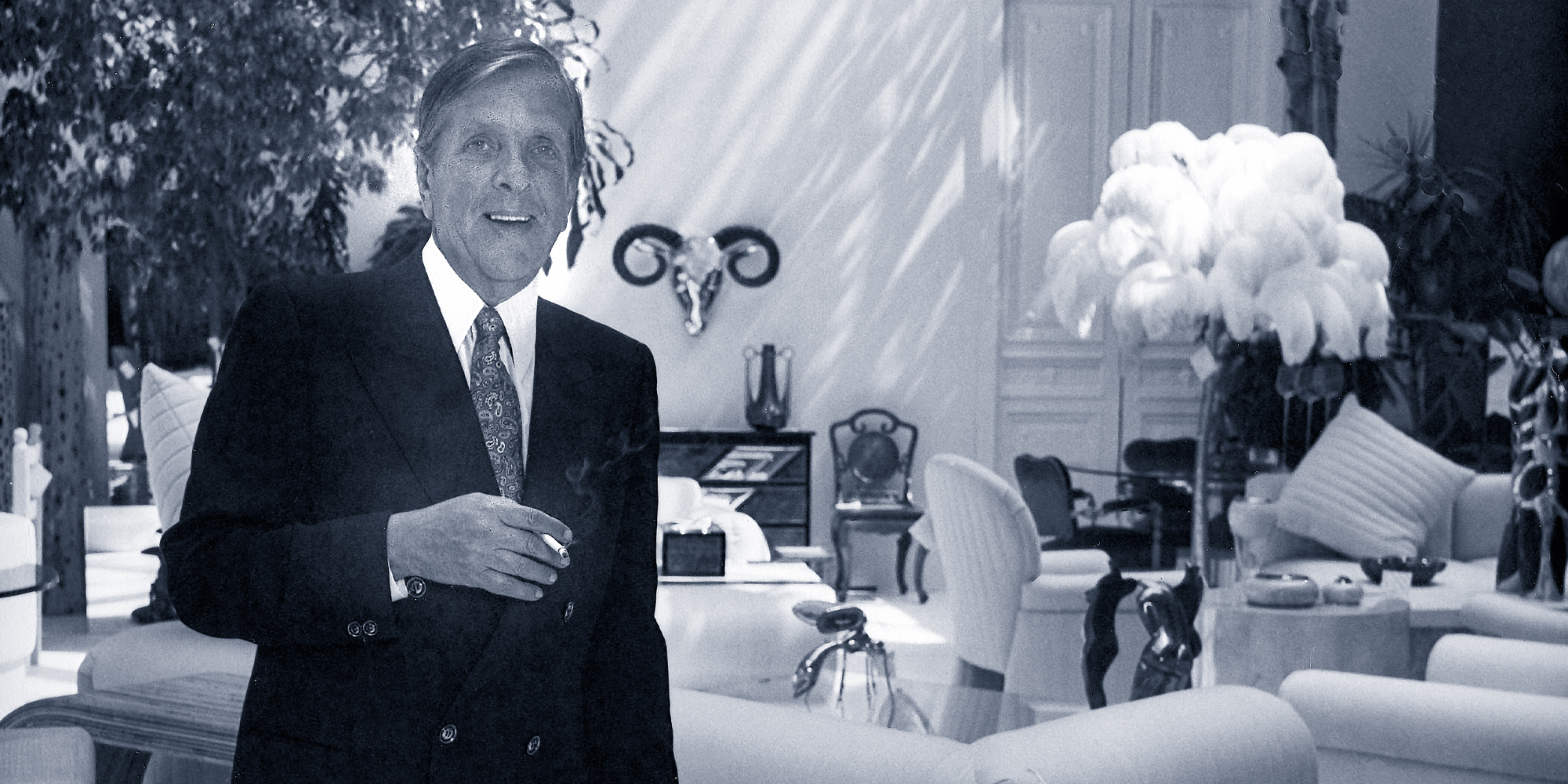

Interior designer Richard Himmel, EX’42, was known for his ebullient personality, his flamboyant taste—which he did not impose on his clients—and his over-the-top book release parties. (Photography by John Reilly)

Decorator and pulp writer Richard Himmel, EX’42 (1920–2000), had a private eye for design.

I pointed to the piano. “You play?”

“A little,” she said.

“Would you play for me?”

“No. I don’t think I’ll ever play again.”

Oh, baby, I was thinking, you’re going to play a lot of things again. You’re going to play a lot of things you never played before.

—Richard Himmel, I’ll Find You

Johnny Maguire—the narrator of I’ll Find You—is right, of course. Shirley is not the demure young Kansas widow she pretends to be. After she fakes her own death, Maguire finds her in Florida, now reinvented as a nightclub singer. A complicated plot, with generous helpings of sex and violence, ensues.

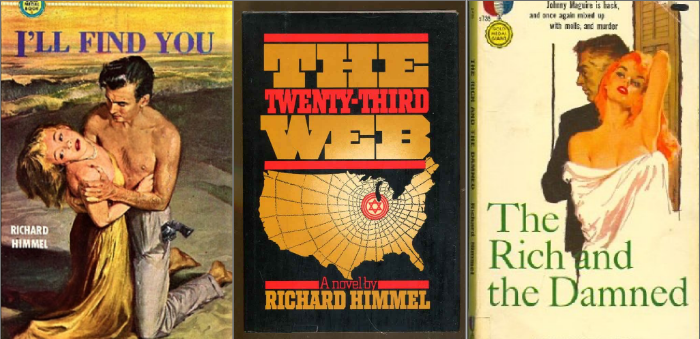

I’ll Find You by Richard Himmel, EX’42, published in 1950, was one of the first paperback originals from Fawcett Gold Medal Books. Short, fast-paced, printed on cheap paper with lurid illustrated covers, Gold Medal paperbacks sold for 25 cents (about $3.00 today) at newsstands, drugstores, and dime stores. I’ll Find You was reprinted five times, and more books featuring self-described “punk” lawyer Johnny Maguire quickly followed: The Chinese Keyhole and I Have Gloria Kirby in 1951, Two Deaths Must Die in 1954, and The Rich and the Damned in 1958.

The series is set in Chicago (though it’s never named), and occasionally Himmel borrows from his UChicago experience or makes in-jokes for the home crowd. In I Have Gloria Kirby, for example, Maguire checks his ex-girlfriend—now a gangster’s moll addicted to heroin—into a hotel under the name “Marion Talbot.” The real Miss Marion Talbot, UChicago’s first dean of women, would have been scandalized. “My mother always said my typewriter should be washed out with soap,” Himmel once said.

But Himmel himself was leading “a double life,” as the headline for a 1951 University of Chicago Magazine article phrased it, hyperbolically. Writing “slick fiction that sells and sells” was just a side hustle. Himmel’s day job—aimed at a completely different set of consumers—was “a best-selling business in swank North Shore interiors.”

In the early 1970s, a New York Times article described Himmel as “Chicago’s most successful interior designer.” In 1985, when the Interior Design Hall of Fame was established, he was among the first group of designers inducted. In addition to the residential work, he designed restaurants, nightclubs, country clubs, banks, and even corporate jets. Yet descriptions of interiors are almost entirely absent from his fiction, which is characterized by short sentences, world-weary observations, and, above all, action.

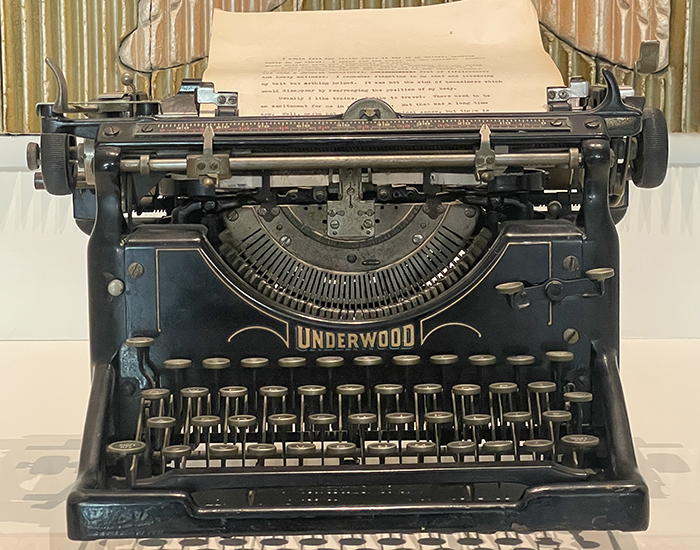

Born in Chicago in 1920, Himmel enrolled at the University in 1938. He studied with Mortimer Adler and Robert Maynard Hutchins, as well as novelist and playwright Thornton Wilder, a part-time faculty member at the time. Described by classmates as “social arbiter of the years ’39 to ’42,” Himmel wrote a gossip column for the Maroon and was its last editor as a daily paper. He was so fond of the typewriter he used as a freshman reporter at the Maroon (illustrated on this issue’s cover), he bought it and pecked out his potboilers on it, using two fingers.

After serving in the Army during World War II, Himmel returned to Chicago and, with his sister Muriel Lubliner, EX’38, cofounded Lubliner and Himmel. The interior design company started as a furniture business, specializing in remaking antiques in unconventional ways: chairs reupholstered with bright modern fabric, musical instruments transformed into lamps or vases. “It’s the design of the piece, not the antiquity and tradition that I respect,” Himmel once told the New York Times. His first interior design project was a half bathroom in a Lake Shore Drive apartment; when he was finished, the client hired him to do the other 17 rooms.

Himmel married Elinor Bach in 1947. The couple had two children: a daughter, Ellen, and a son, John Maguire Himmel, named after his novels’ Irish protagonist.

In the evenings Himmel worked on his first manuscript, “Heart of the Wilderness.” The dark, brooding story centers on a love triangle: after Jack is killed in the war, his widow, Kit, and his best friend, Rocky, try to make sense of their grief. Although homosexuality is condemned—in a scene in a Paris hotel room, when Jack confesses the true depth of his feelings, Rocky punches him out—their relationship is portrayed sensitively and sympathetically. Literary publishers rejected the manuscript, but it was released as a pulp novel, Soul of Passion, in 1950.

Himmel gave up moonlighting after the fifth Johnny Maguire book, The Rich and the Damned, appeared in 1958; he stopped publishing for almost 20 years as his design career flourished. Although he was discreet about his residential clients, he was known to have worked for Muhammad Ali, gossip columnist Irv Kupcinet, and Saul Bellow, EX’39. Himmel was successful, according to a 1971 New York Times article, because he did not impose his taste on his clients: “You tell me, baby, how you live and what you like,” he would say, “and I’ll deliver it.”

Himmel’s own living spaces were as unapologetically splashy as his fiction. His library in the 1970s, for example, had a mirrored skylight, floor-to-ceiling windows, a collection of Napoleonic figurines, a Mickey Mouse telephone, and all of the books—including the first editions—covered in plain white dust jackets. “Outrageous?” he told the New York Times. “Far from it, I call it serene.”

In the 1970s and ’80s Himmel returned to writing, publishing three hardcover spy thrillers: The Twenty-Third Web (Random House, 1977), Lions at Night (Delacorte Press, 1979), and Echo Chambers (Delacorte Press, 1982). (Himmel’s release parties were legendary: for Lions at Night, set in Cuba, he rented a parking lot on Michigan Avenue and brought in lions and men in guerrilla fatigues.) His final manuscript, “The Uncircumcised Jew,” never made it into print.

When Himmel died in 2000 at age 79, he was primarily known for his design work, while his writing—despite the millions of books sold—had fallen into obscurity. In 2019 publisher Cutting Edge Books began reissuing his novels as stand-alone paperbacks (sadly, with far less arresting covers) and in collections with other writers. The Complete Works of Richard Himmel, with all 12 of his published works, was released as an e-book in 2020.

Himmel’s novels were intended to shock, and they still do. He was unembarrassed by his subject matter, with one exception: “I am always afraid,” he told the Magazine in 1951, “that Norman Maclean [PhD’40] will pick up one of my books in an El station, and send it back to me, corrected like one of my old themes.”

In Himmel’s work, sex is celebrated, never punished or shamed—even in the books from the early ’50s. Women characters are not weak: when slapped (as happens not infrequently), their typical reaction is contemptuous laughter. Himmel’s books are transgressive in ways that are both disturbing and exhilarating. They’re also stylish, escapist, breezy, and almost impossible to put down.

Updated 02.14.2022 to note Muriel Lubliner’s affiliation year.