John Himmel on his father, Richard Himmel, EX’42

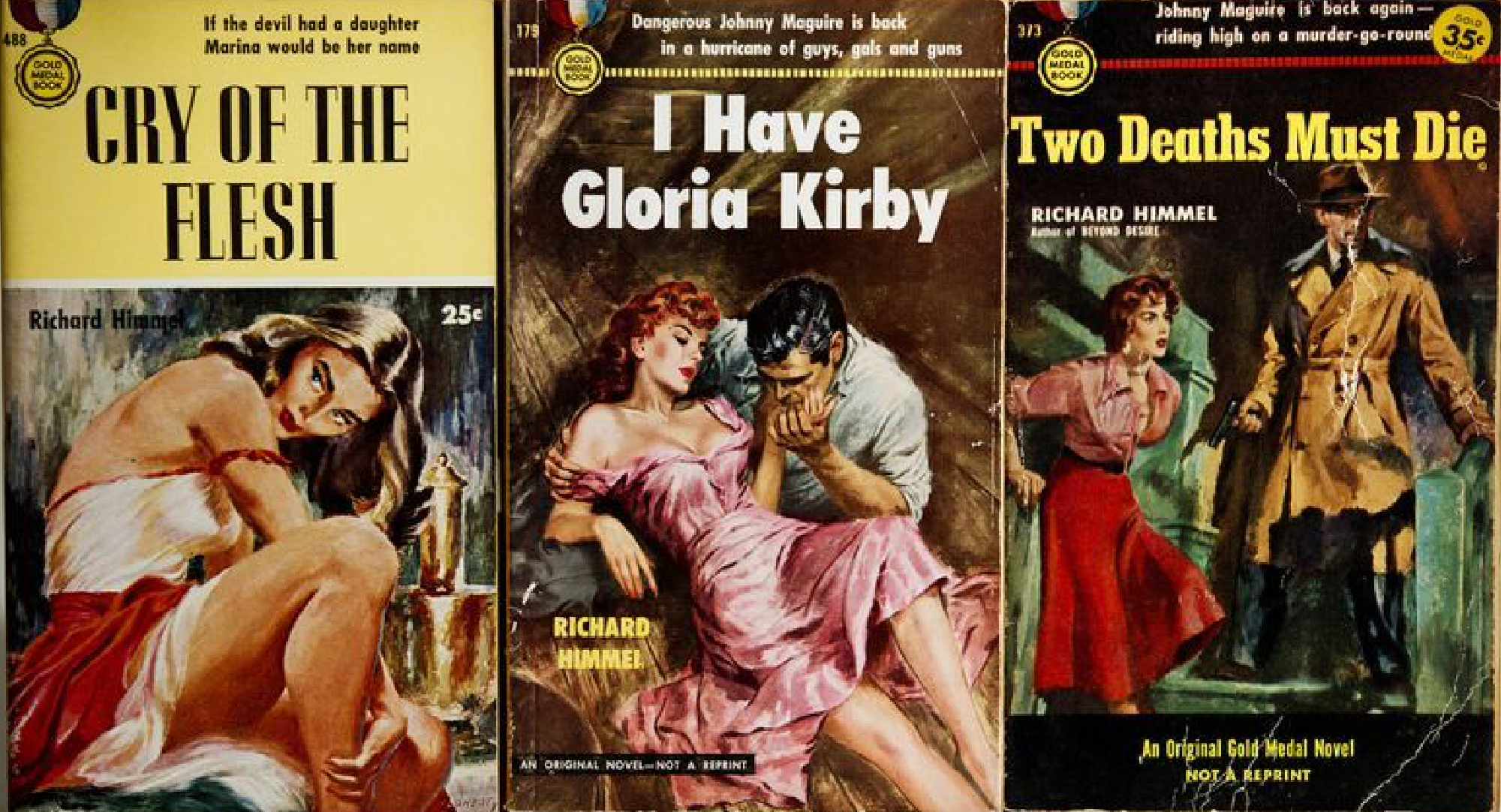

When Richard Himmel, EX’42, and his wife Elinor had a son, they named him John Maguire Himmel in honor of Johnny Maguire, the protagonist of five pulp novels that Himmel published in the 1950s. “It’s my free pass on St. Patrick’s Day,” John Himmel says.

As his father’s literary executor, he worked with Cutting Edge Books to collect 12 of his father’s novels into an e-book, The Complete Works of Richard Himmel, published in 2020. He spoke with the Magazine about Richard Himmel’s dual careers as a writer and an interior designer—and what he was like as a father.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

How did The Complete Works of Richard Himmel come about?

Lots of his work was already in the public domain. I got a call from a guy named Tom Simon, who has a website called the Paperback Warrior. He wanted to discuss my dad and his work. He works in collaboration with Lee Goldberg, who runs Cutting Edge Press.

I have all of the first editions, as well as some of his unpublished work. I’ve got his original typewriter, still with a manuscript in the roller.

Was your father ever approached by Hollywood? His books seem like they’re crying out to be made into movies.

They wanted to make The Chinese Keyhole [1951] into a movie. It never materialized.

It did stimulate my dad’s thoughts about the movie business. He was a big reader and a big fan of Ian Fleming. He tried to make a deal for the rights to Ian Fleming’s work. It was like $1,000 shy of what they were looking for.

Your grandmother once said your dad’s typewriter should be washed out with soap. What did your mom think?

She never talked about it. Nor did my dad talk about it too much. I think they were a little embarrassed about the work back then, because it was pretty spicy—though today it seems so bland.

They were two incredibly opposite personalities. My mom was basically raised as an only son. She was a jock and a sports fan. Beer drinking, cigar smoking—she was about 4′11″ and 90 pounds. She was a season ticket holder for the Chicago White Sox. I’d go to baseball games with my mom and flower shows and antique shows with my dad.

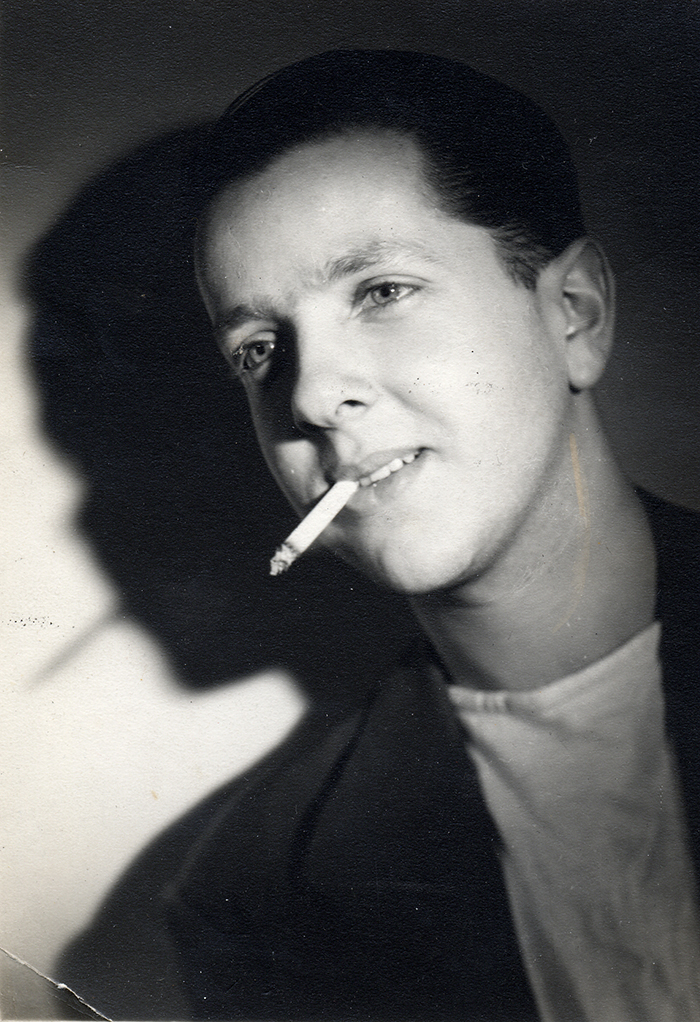

My dad was totally bookish. The only time I ever played catch with my dad, he jammed his finger and said, I’ll never do that again.

Do you have a favorite book?

The Twenty-Third Web, which was the first of his second life as an author. It’s pretty terrific work. Very cinematic.

I categorize his writing into his first career and his second career. They’re like two different authors. He took a 20-year hiatus from publishing because he was so incredibly busy with his design work, but he was always thinking about it.

How are the two periods of his writing different?

In a way that’s emblematic of the times. The ’50s work was naïve—kind of dirty naive. And the other one was full ’60s, ’70s. More of a happening.

In his later works, the ’50s mores went away. The last, unpublished book was way out there. I mean, way out there.

The Uncircumcised Jew?

That would be the one.

Besides being a writer and an amazing interior designer, he was a pretty good artist. He had immersed himself in the New York art scene in the ’60s. This book showcased the different characters in the New York scene, and his character was put right in the middle of it.

Did he always write under his own name, even with the books’ racy content?

Yes. My mother might have been embarrassed. My father was never embarrassed. He was an in-your-face type of guy. If he was embarrassed, would he title a book The Uncircumcised Jew?

What does that title even mean?

Well, this may be a little too psychological, but when he was growing up, Judaism was all about assimilation into the American fabric. My dad was quite Jewish. I have a Bible of his that’s just worn out from use.

And yet a lot of his characterizations were kind of repudiating the religious part of his life and trying to assimilate. He never thought that either my sister or I would have a religious education. That says it all.

Did your dad do research for his books? Or did he just let his imagination run wild?

He did a lot of research. Because of his work in antiques and design, he would travel the world. He was always very specific with references in his books. He actually had a couple of research assistants.

What was his writing routine?

I think writing filled time for him. He didn’t sleep very much. He would work late at night and early in the morning—he’d write before going to work. When I was little and trying to get to sleep, or early in the morning when I was getting up, I’d hear that ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch [sound of a manual typewriter]. He always had a cigarette hanging out of his mouth.

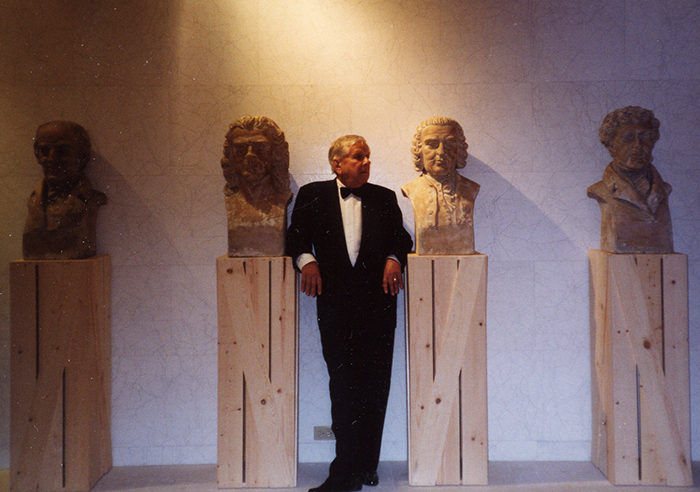

How was he able to be so successful as both an interior designer and a fiction writer?

My dad was a generic genius. It didn’t matter what he did. He was brilliant.

When he went into the service during World War II, he went directly onto General Patton’s staff. They would throw things at him: we need a pamphlet for how to recognize Japanese aircraft. He would just do it.

The one thing that seems to unite your dad’s two careers is he’s so bold and unapologetic—willing to take a lot of risks.

Absolutely. He was always able to take something and have a new vision for it. He would repurpose objects—make them into chandeliers or lamps, or take antiques and doll them up.

And his clients liked that?

That’s why people hired him. It was bold but beautiful.

In his design work my dad always wanted to enhance his clients’ living. Whatever they wanted to do—throw lavish parties, have a private workspace—he tried to enhance their lives through their environment.

All of his jobs are different. He could do traditional French or English, or ultracontemporary. His vision was not his. It was his client’s wishes—through his eyes and his aesthetic.