Lunch and Greppo at the Center in Paris. (Photo courtesy Sébastien Greppo)

Lydia Lunch reads William S. Burroughs, even though she doesn’t really like his work.

I’ll admit it: when I was 17 and first heard of Lydia Lunch, she really freaked me out.

I knew hardly anything about her work. And still she freaked me out.

She’d been in a Richard Kern film called Fingered (1986), which I didn’t see, but I saw some stills, and that was plenty. She’d been in bands with names like Teenage Jesus and the Jerks, and did spoken word, and was aggressive and sexual in a way that made me deeply uncomfortable. It wasn’t so much the work itself, really. It was the reaction from a vocal minority of her fans, who seemed to appreciate it for creepy, even misogynistic reasons.

Decades pass. Then earlier this month, I unexpectedly have the opportunity to see Lydia Lunch in person for the first time. For free. At the University of Chicago Center in Paris. She’s been invited to read some of William S. Burroughs’s work for a celebration of the 100th anniversary of his birth.

The venue—the center’s small, cozy library—could not possibly be less creepy. Lunch is now 55 years old, and though she’s still wearing all black, with her long black hair cut with a thick fringe, she’s just not scary anymore. Or maybe I’m not scared anymore.

“Any questions before I begin?” she asks the audience of about 50 people—mostly undergrads whose parents probably would have needed a fake ID to get into Lunch’s early performances. When no questions are forthcoming, she starts asking the questions: easy ones, like where people in the audience are from.

This is Lunch’s fourth time performing at the Center in Paris. Lunch, who lives in Barcelona, is a personal friend of Sébastien Greppo, the center’s administrative director. They met at one of her shows, she explains: “I went up to him because he was nervous. I’m a confrontationalist. I said, who are you and why are you at my show again?” Last summer, Greppo even went on a seven-city North American tour with Retrovirus, one of the four bands Lunch currently performs with. Greppo rode in the van and helped schlep equipment at gigs from Louisville, Kentucky, to Chicago to Buffalo, New York.

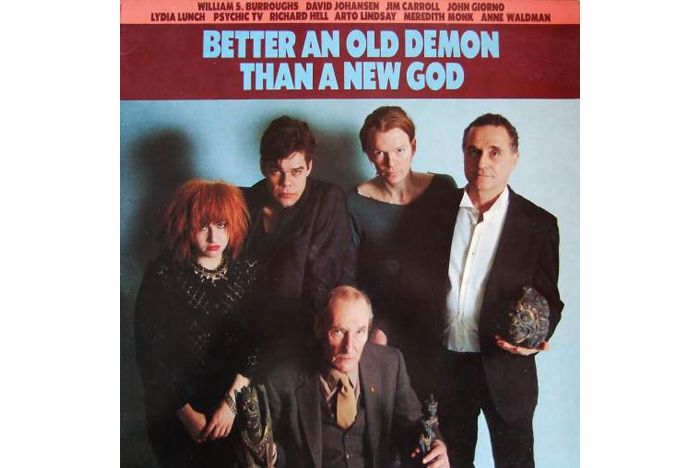

As he introduces Lunch, Greppo holds up his own copy of a 1984 spoken-word album, Better an Old Demon than a New God, which features Burroughs and Lunch, as well as Jim Carroll, Richard Hell, Psychic TV, and others. Lunch, who has dropped perhaps 10 f-bombs by this point in the evening, notes that Burroughs wrote a lot of books that she didn’t like at all. Her exact quote was stronger.

She puts her glasses on, opens a paperback copy of Naked Lunch, and begins to read about safety pins, heroin, and a woman who looks at her own hacked-up leg with the dispassion of a butcher. Her voice is deep, husky, and powerfully charismatic.

She closes the book, slips her glasses off, and reads a piece of her own about not being able to save an emotionally wounded person. “The longer that you love a damaged person, the more it’s going to hurt you,” the piece concludes.

She looks up. “I’d say,” she says. “Burroughs would say ...”

And it’s back to Naked Lunch. The title, she notes, was suggested by Jack Kerouac. The audience listens intently: every face in the room is turned toward hers. Lunch cuts to her own writing, then to Burroughs again, then back to herself. It’s another piece about an addict she loved: “I want to be saint, savior, and favorite sin.” She matches that in a moment with what she considers to be Burroughs’s “most brilliant line”: “the algebra of need.”

After the reading, the audience finally asks its questions. A man in a tweed jacket wants to know if her last name—she was born Lydia Koch—is an homage to Burroughs. It isn’t. When she first moved to New York, Lunch explains, she worked in a bar so she could steal food for her friends: Lydia Lunch.

The nickname “was like glue. I couldn’t get rid of it,” she says. “What I do with writing is to feed the soul.” Last year, she even wrote a cookbook, The Need to Feed. (“Literally every recipe I’ve made is a winner,” wrote one Amazon reviewer, whose favorites include “Spicy Pork Roast and Sauteed Spinach with Pine Nuts and Raisins.”)

Lunch doesn’t have any copies of that, but she does have Paradoxia: A Predator’s Diary (2007), though only in French translation. The autobiographical book is about “my sexual landscape,” she says, as a “victim of family trauma.”

Later the man in the tweed jacket has a second question: how does she respond to her critics, people who think her work is “a handbook for miscreants”?

Lunch bristles. “What’s wrong with that?” she wants to know. No one has the right to criticize her life, she adds.

“Word,” the man says softly.

“I’ve never been insulted in my life once, because an insult does not penetrate me,” she says. Then she brings up Fingered, “a pretty controversial film,” which is either “misogynist or a feminist classic,” about how a victim becomes a victimizer.

“Guys, if you haven’t seen Fingered,” she says, “don’t. It’s too hard.”

With that, the question and answer is over and it’s time for the reception. “Thank you all for coming here,” she says. “Who would like a drink or a snack?”