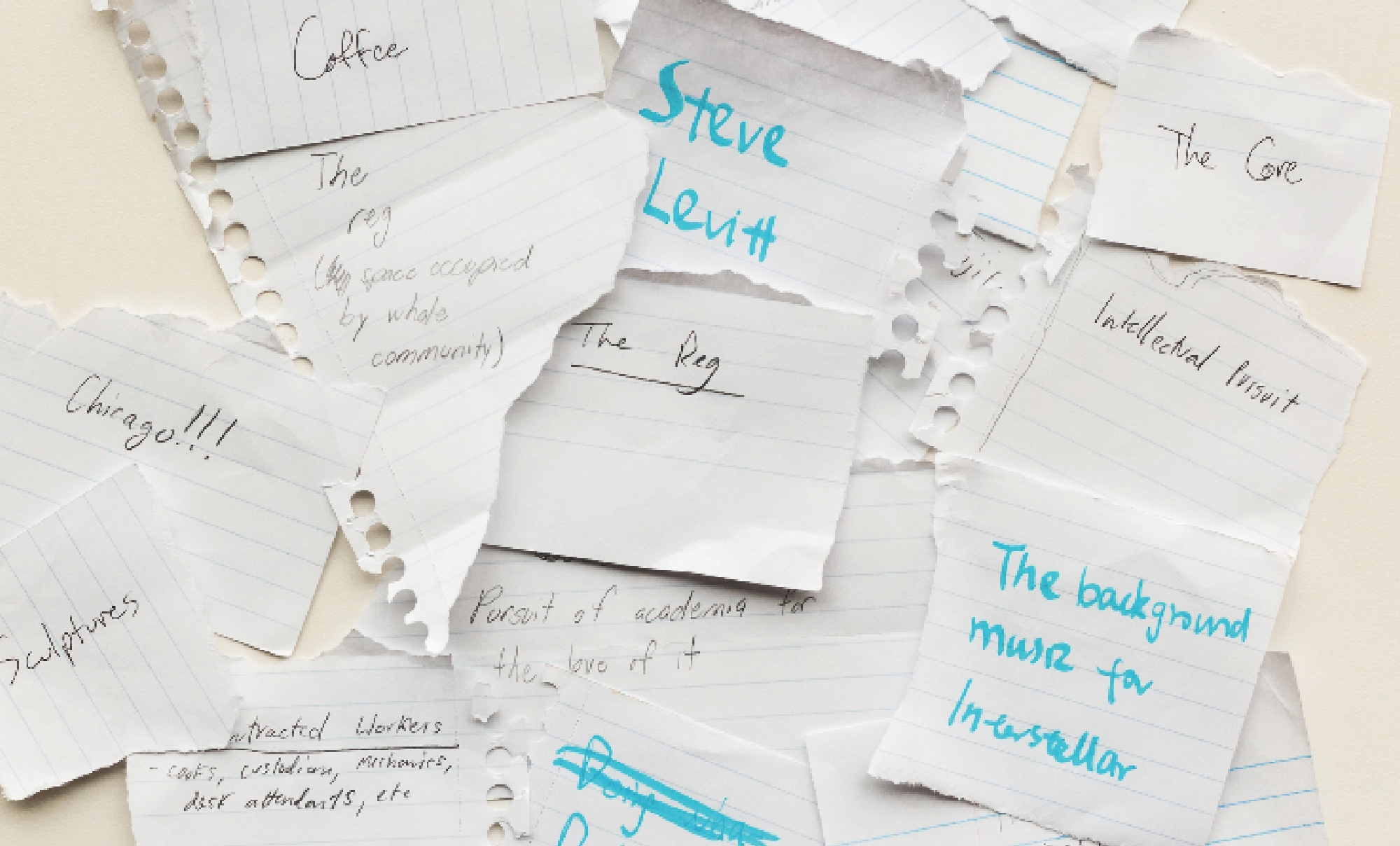

The results of a straw poll of the Exemplary student interns to determine which people, places, or things best exemplify the University of Chicago. The consensus: not much consensus. (Photography by John Zich)

A new public art project, Exemplary, asks who we honor at UChicago and why.

On Monday mornings at 8 a.m., the Logan Center for the Arts is almost entirely deserted. But for the five overscheduled student interns working on the public art project Exemplary, 8 a.m. Monday was the only free slot on all their schedules.

“Kinda hard core, right?” Laura Steward, UChicago’s curator of public art, observes. For this particular project, designed to celebrate an exemplary UChicagoan, it seems appropriate. The group meets in a classroom on the sixth floor. With its white tables, whiteboards, and wall of east-facing windows, the room is like a blank slate.

It’s October 24, the interns’ second meeting. Steward, who came up with the idea for Exemplary and is overseeing the yearlong project, is out of town. So the five paid interns—Juan Cardenas, William Hu, Suttyn Simon, Xueqi Sun, and Miki Yang, all second-years—have gathered without her. Their first task, focused on audience, is to finalize a survey to gather students’ opinions.

“What are the qualities of a UChicagoan?” the questionnaire asks. “Please choose three to five.” The options:

- Intellectual

- Inquisitive

- Quirky

- Curious

- Diverse

- Passionate

- “Life of the Grind”

- Inspirational

- Worth imitating

- Lifelong scholarship

- Free speech

- Eloquent

- Maroon pride (against Northwestern/Harvard?)

- Where fun goes to “hype”

- Econ bro

(“Econ bro,” named in honor of the many business-economics majors at UChicago, is a drink sold at student-run café Ex Libris, Xueqi explains later.)

The survey includes a blank to write in a current professor “who embodies qualities of a UChicagoan,” as well as objects that “remind you of a UChicagoan,” such as coffee or a dollar milkshake.

There’s also a list of 20 exemplary alumni and faculty, past and present—mostly usual suspects, with a few not-so-usual mixed in. Again, respondents are asked to choose three to five.

The alumni include dancer-anthropologist Katherine Dunham, PhB’36; composer Philip Glass, AB’56; baseball general manager Kim Ng, AB’90; astronomer Carl Sagan, AB’54, SB’55, SM’56, PhD’60; Vermont senator Bernie Sanders, AB’64; and writer Susan Sontag, AB’51.

The faculty choices skew toward the famous and the past: philosopher Hannah Arendt, physicist Enrico Fermi, meteorologist Tetsuya (“Ted”) Fujita, former president Barack Obama. Two of the options—economist Milton Friedman, AM’33, and former UChicago president Edward Levi, LAB’28, PhB’32, JD’35—fall into both categories. There’s also a space to write someone in.

“Can we agree on one exemplary person?” Xueqi asks the group.

“No. I don’t think we’re lining up on it,” William says.

“A long way to go,” Xueqi says, laughing.

Exemplary is the College’s first full-scale public art project, with a budget of $40,000. Last academic year Steward ran a pilot project, 100 Views of Lake Michigan, also with a small team of interns. Inspired by Hiroshige’s series of woodblock prints Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, the project collected crowdsourced photographs of the lake and displayed them around campus. (See the “On the Horizon” from the Summer/22 issue of the Core.)

The idea for Exemplary grew out of a public art seminar Steward taught in 2021. Steward, who came to UChicago in 2017, had discovered there was a bronze relief in the Reynolds Club honoring Senator Stephen A. Douglas, a slaveholder who donated land to the first University of Chicago (1856–86), which went bankrupt. The Class of 1901 donated the plaque as part of the new University’s tenth anniversary celebration.

In a 2018 article in The Journal of African-American History, Caine Jordan, AM’17; Guy Emerson Mount, AM’18, PhD’18; and Kai Perry Parker, AM’16, PhD’19, explain how an elected representative from a free state could also own a slave plantation. In 1847 Douglas, then a US representative, married Martha Martin, whose father owned a Mississippi plantation with 150 enslaved people. Martin’s father died soon after, leaving the estate to the Douglases in his will—under her name. According to a contemporary description, “Mr. Douglas’s slaves in the South were the subjects of inhuman and disgraceful treatment … they were spoken of in the neighborhood where they are held as a disgrace to all slave-holders and the system they support.”

In 2020 Steward, who oversees the art and other objects displayed in University buildings, worked with the president’s office to have the Douglas plaque removed to the Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections Research Center. In her seminar, she assigned students to consider what might hang in its place: “In theory that leaves a blank space on the wall in Reynolds. What should we put there?”

She particularly liked one student’s proposal: a bronze plaque with a quotation from Sontag. Steward had anticipated that Exemplary might focus on Sontag or another graduate of the College.

But at the first meeting, she discovered the interns had little interest in alumni from the College specifically. Instead the discussion focused on the Core curriculum, UChicago people more generally, and people who were still alive—not Sontag or other exemplary alumni of the past. Dean John W. Boyer, AM’69, PhD’75, was suggested. Juan surprised the group with his idea to honor the workers at UChicago as a collective, rather than focus on one exemplary individual.

“They’ve already moved quite far from where I thought we were going,” Steward said in an interview after the group’s third meeting. “So that’s a little heartbreaking for me, because I did have ideas of my own. But it’s much more important to surface theirs.” Unlike a typical curatorial internship, the students are driving the project with Steward’s support, rather than the other way around.

By the November 7 meeting, several of the students have interviewed various department and program chairs to get their thoughts on what exemplary at UChicago might mean. William talked with Andreas Glaeser in sociology, Suttyn with Peter Littlewood in physics, and Xueqi with Malynne Sternstein, AB’87, AM’90, PhD’96, in Fundamentals: Issues and Texts. “I didn’t even have to ask her questions,” Xueqi says. “She just started pulling up all her memories.”

In Sternstein’s view, the fundamentals program “is the real UChicago,” Xueqi tells the group. “UChicago people are constantly asking questions. They are always curious about the world.” And while the College has grown since Sternstein was an undergrad, “that is something that hasn’t changed since the 1980s.”

The discussion circles back to a topic picked over in previous meetings: whether today’s College students have the luxury of pursuing learning for its own sake, or if there’s too much pressure to lay the groundwork for a career. And if so, should the project respond to that?

Along the way, there are numerous digressions into topics inspired by Xueqi’s interview with Sternstein: the Lascivious Costume Ball, Botany Pond (unavailable as a project site, Steward notes, since it’s closed for renovation), the “secret pathway” that allows you to walk between Harper and Cobb without going outside. Steward wonders if the project is becoming too driven by nostalgia: is it backward-looking to focus on the University’s past, rather than look to its future?

“I think it’s important to limit the scope,” William says. “Right now the project feels very discombobulated.”

“It’s at its maximum aperture,” Steward agrees.

“We started with the idea to showcase a person,” William says. “I think it’d be beneficial to figure out the function of the project itself.”

“Can we do that in 30 minutes?” Juan wonders.

“Unfortunately, I have one more thing,” Suttyn says: the University itself has not always been entirely exemplary. “Professor Littlewood talked about the concept, specifically in the physics department, of original nuclear sin. He said everyone in the physics department always keeps this in mind.”

Meanwhile, Juan has been perusing the student survey results on his laptop. In the space for write-in candidates, “Someone put Miki’s name,” he says.

“As an exemplary person?” Steward asks. “That’s awesome.”

“Awww,” Suttyn says.

“I think it’s from Patrick,” Xueqi says.

“He’s my friend,” says Miki, “so disregard that answer.”

“Okay,” Steward says, “the date is November 7.” With just over four weeks left in Autumn Quarter—the quarter devoted to researching and planning the project—Steward proposes a straw poll to try to find something everyone can agree on, “be it the Reg or Bernie Sanders,” she says. “Does anyone have any paper?” Two of the five students do. They share it around. “Write down five things—people, places, objects.” There’s the sound of paper tearing.

“Do these ideas have to be realizable?” Suttyn asks. “Or can it be a little more conceptual?”

“At some point it will have a physical form in the world,” says Steward. “If we can’t come up with the right form for it, then we’ll have to leave it aside.”

Steward puts on some music for the students to think to. The students struggle to distill their wide-ranging ideas down to five concrete suggestions: “I need two more,” Juan says when Steward asks if anyone is done.

“I need one,” says Miki.

Finally the votes are in. Steward spreads the scraps of paper out on the table, then shuffles them, searching for patterns. “I’m confused,” she says. “This is a mess.” The students laugh.

“Can I see?” Miki asks.

“Hold on,” Steward says, still shuffling.

“This is an election,” Juan says. “A democratic process.” Coincidentally, the music Steward is playing (“Cornfield Chase,” from the 2014 Interstellar soundtrack, at Miki’s request) surges to an emotional climax, for an oddly movie-trailer-like effect: “Do we value democracy at UChicago?”

“We have five for the Reg,” Steward says. The students burst into cheers and applause.

“We have three people,” she continues. “Steve Levitt [the William B. Ogden Distinguished Service Professor in Economics], Bernie Sanders, and Tetsuya Fujita.”

“We have,” she says, looking over the other scraps, “the Core, intellectual pursuit, intellectual curiosity, pursuit of academia for the love of it, pursuing professional life with a social mission.” Other suggestions are harder to categorize: Sculpture or statue. Contracted workers. Coffee. The background music for Interstellar.

“So this is your job for this week,” Steward says. “How would you make a temporary monument to the Reg? It’s a hard problem, because the Reg is already a big fat monument to itself.”

“I hate going to the Reg,” Juan observes.

“What?” says Steward.

“Me too,” say Suttyn and William, almost in unison.

It’s the Brutalist architecture, Suttyn explains: “There’s a whole beautiful campus, and then you’re walking into this giant concrete monolith.”

“That is the most beautiful building on campus, by far,” Steward states firmly. “The Reg.”

“Yeah?” Suttyn says. The students, despite their unanimous vote, look unconvinced.

On the Monday after Thanksgiving, only three students—Miki, Suttyn, and William—are at the regular 8 a.m. meeting. Juan and Xueqi are out sick.

The project has circled back to exemplary people. Hoping to get some consensus, William sent out a poll over the break. The results: Susan Sontag and Carl Sagan are in the lead, with four votes each. Ted Fujita, Enrico Fermi, Philip Glass, and John Dewey each received two.

“What happened to Katherine Dunham?” says Steward.

Suttyn, a former professional ballet dancer and Dunham’s biggest advocate, forgot to add her to the ballot. “I’m still going to plug Katherine Dunham if you guys want to look her up,” she says. Both William and Miki seem open to the idea.

“If it were Sontag, Dunham, Sagan, Fujita, and one more … ” Steward says thoughtfully. “Five is an arbitrary number, but a good number. And we still have the Reg, which you were interested in, and also the workers.” But those are difficult questions. No one has any immediate suggestions for how to integrate a building, or an acknowledgment of UChicago’s workers as a group, into a project focused on elevating individuals for their achievements.

The idea of doing a project on Sontag “has been kicking around in my brain for a while,” Steward says, “so that’s probably why it’s more developed.” She suggests sharing excerpts from Sontag’s writings—perhaps by reading them aloud, or by displaying her words.

The discussion shifts to potential spaces. “Reynolds is a good space to work in because it’s controlled by the College,” Steward says, and in addition, “there are already plaques honoring UChicagoans there. To insert her into that space would be cool.”

A sound installation somewhere on campus is another possibility. “I’ve done an installation in Cobb Gate before. It’s a good place to do sound, because there’s power,” she says. “Another good spot is Wieboldt passage. We could put speakers and have 24/7 Against Interpretation”—Sontag’s 1966 essay collection.

Brilliant, almost blinding light is streaming in from the east today, but the energy in the room is atypically low. Even with the return to Steward’s original conception of the project, there’s still so much to choose and decide—and finals are looming.

“It’s 9:30,” Steward says. “I think we should move on this plan.” She proposes a quick trip to the Reynolds Club, to imagine how a Sontag installation might fit in.

It’s a picture-perfect late fall day. Steward pauses in the arch between Classics and Wieboldt. Would it work for an installation on Sagan—perhaps a video installation of his television series Cosmos? It’s a strange space: beautiful, but somewhere that people pass quickly through, without lingering.

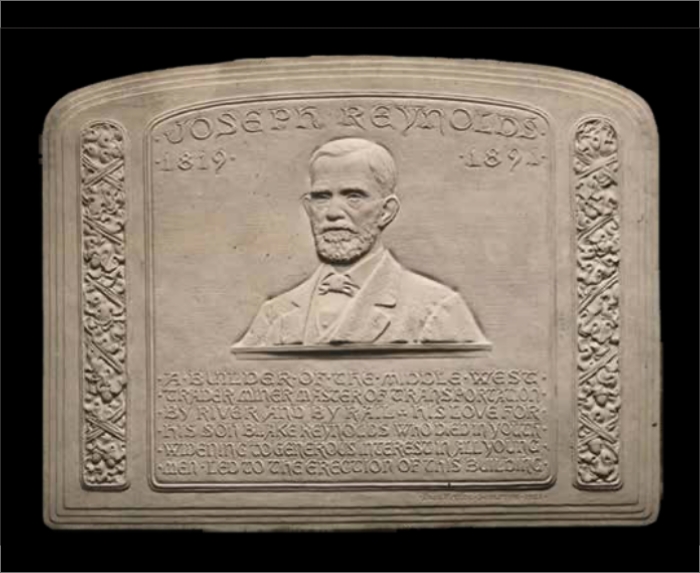

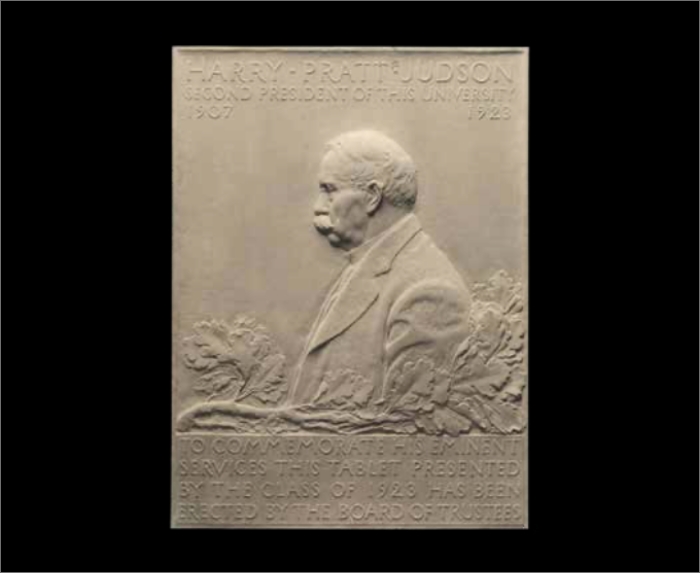

In the Reynolds Club, the group walks through a similarly liminal area outside Mandel Hall. “This is such an empty space,” Miki says. In fact the walls are crowded with plaques that are mostly ignored by passersby. There’s a stone tablet for Martin Antoine Ryerson, acknowledging his 30 years as president of the board of trustees. A bronze tablet to Harry Pratt Judson, with a bas relief of him in profile, “to commemorate his eminent services.” A large bronze plaque memorializing steamboat entrepreneur Joseph “Diamond Jo” Reynolds, for whom the Reynolds Club is named.

Until recently, the Stephen Douglas plaque was among them.

Steward leads the group into Hutchinson Commons. In the golden autumnal light, the dining room looks about as glorious as it is possible to look. The sun streaming through the southern windows makes rectangular patches on the northern wall, overlapping the portraits.

“A lot of white men,” Miki says.

“A lot of white men,” Steward says.

On the southern wall, a portrait of Marion Talbot, dean of women in the early University, hangs above the table closest to the door. Steward draws an imaginary square on the wood-paneled wall underneath it. “What if there were a flat screen here?” she says.

“At lunch and dinner, it would be too loud,” Miki says. At the next table over, a man sitting by himself is speaking loudly in Spanish, as if to underscore her point.

Steward’s other suggestion is to display Sontag quotations on vinyl banners on the walls or tables. “I’ll have to reach out to the provost to see if we can work in here,” she says. “Should all the projects be in this room?”

“Sontag and Dunham would work in here,” Suttyn says. “I don’t know how much Sagan would.”

The students look with fresh eyes at the familiar hall. Every surface is dense with decoration: wood paneling, portraits, leaded windows, wooden beams, chandeliers, patterned carpet. Nothing is blank enough to lend itself to an appreciation of outer space. “I do like Sagan in Wieboldt,” Suttyn says.

It’s nearly ten o’clock. Steward reviews everyone’s assignments for the coming week.

“How do you feel?” she asks the group. Everyone is nodding—they’re still a little underpowered, but they seem optimistic. After weeks of discussions, digressions, and frustrating dead ends, the project is finally beginning to take shape.

Read part two of “Making an Example” in the Summer/23 Core.

Exemplary interns

If you were in charge, the Core asked the interns—and had an unlimited budget—what would your dream Exemplary project be?

Juan Cardenas

Hometown: Waukegan, IL

Majors: Art history, sociology

Dream project: A monument commemorating campus workers, who are often “unseen and unappreciated.”

William Hu

Hometown: Princeton, NJ

Major: Sociology

Dream project: A festival featuring many exemplary people with activities and food inspired by them.

Suttyn Simon

Hometown: Hollywood, FL

Majors: Art history, political science

Dream project: “The best part of this project is it incorporates all of our voices. I can’t really fathom one that doesn’t include all of us.”

Xueqi Sun

Hometown: Beijing

Major: Fundamentals: Issues and Texts

Dream project: More communal spaces on campus for “the collision of ideas to happen.”

Miki Yang

Hometown: Chengdu, China

Majors: Art history, economics

Dream project: More women’s portraits on the walls of Hutchinson Commons.