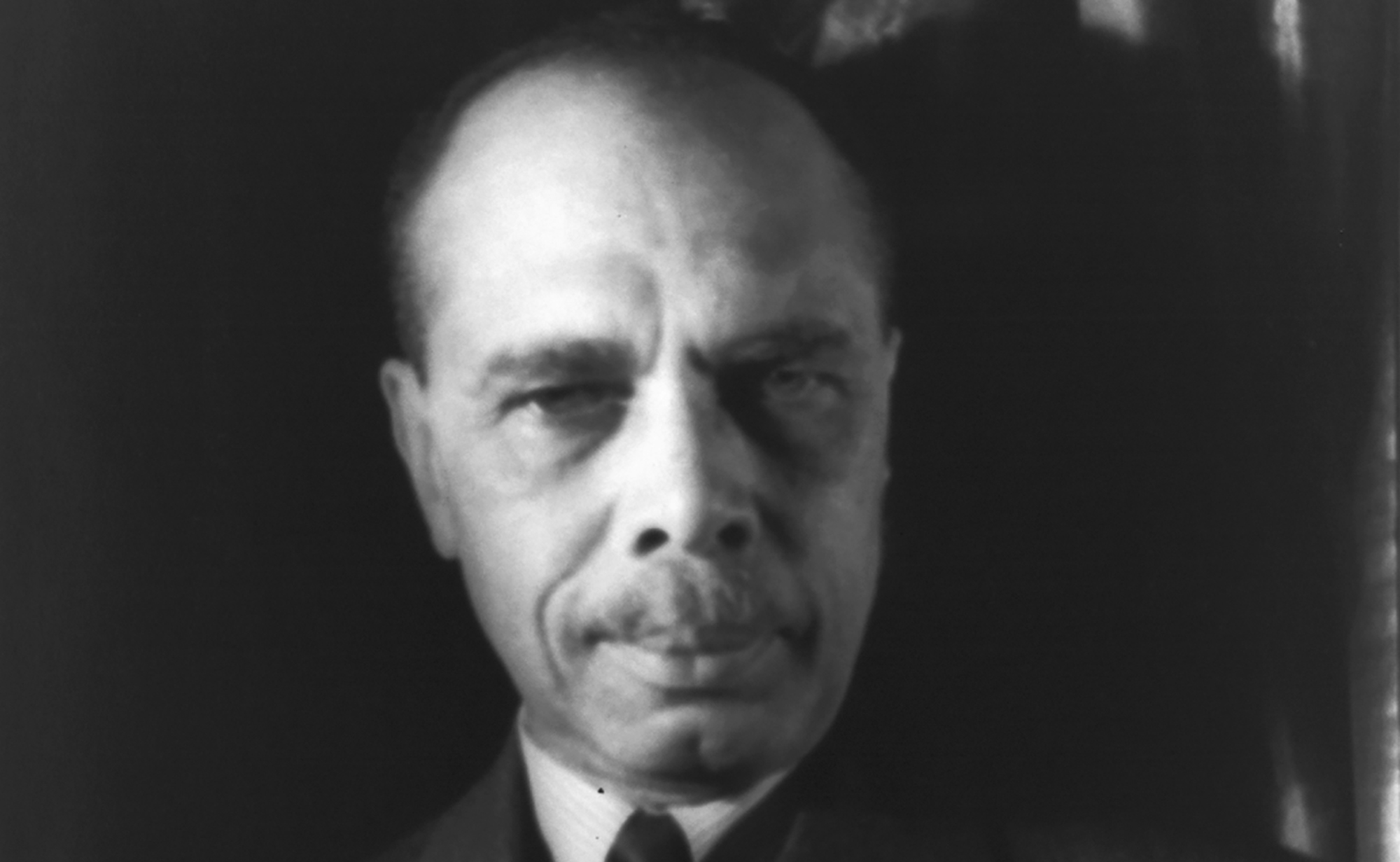

James Weldon Johnson’s influential anthologies of spirituals preserved material Ramey considers foundational to African American poetry. (Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Carl Van Vechten [PhB 1903] Collection, LC-USZ62-42498)

Lauri Ramey, AM’75, PhD’96, traces a 400-year literary legacy.

When Lauri Ramey was teaching English and creative writing at Hampton University in the late 1990s, she founded the school’s African American Poetry Archive. Gathering the historically black university’s rich holdings in poetry, she also acquired new materials from contemporary writers who were inspired by the idea of a central repository for their tradition and wanted their work to be preserved there.

Two decades later, Ramey, AM’75, PhD’96, continues to advocate for a revised American literary canon, one that acknowledges the central place of African American poets. In A History of African American Poetry (Cambridge University Press, 2019), a comprehensive account of a 400-year legacy, she makes the case for African American poetry’s fundamental place in American culture by defining it as a tradition that predates the nation’s founding.

What is it that makes African American poetry one continuous tradition? For Ramey, it’s the body of slave songs like “I Know Moonrise” and “Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen,” which she considers the origin point and touchstone for the African American literary expression that followed.

“Poets are constantly talking to other poets,” past and present, says Ramey, who now runs the poetry centers she founded at both California State University, Los Angeles, and Hunan Normal University. When African American poets talk to the slave songs’ “black and unknown bards,” in New Negro Renaissance writer James Weldon Johnson’s phrase, they speak as both conservators and innovators. This, for Ramey, is the essence of African American poetry—the “tremendously resilient core that preserves its identity even in the face of a lot of political pressure to assimilate,” and allows it to embrace “an equally strong process of regeneration.”

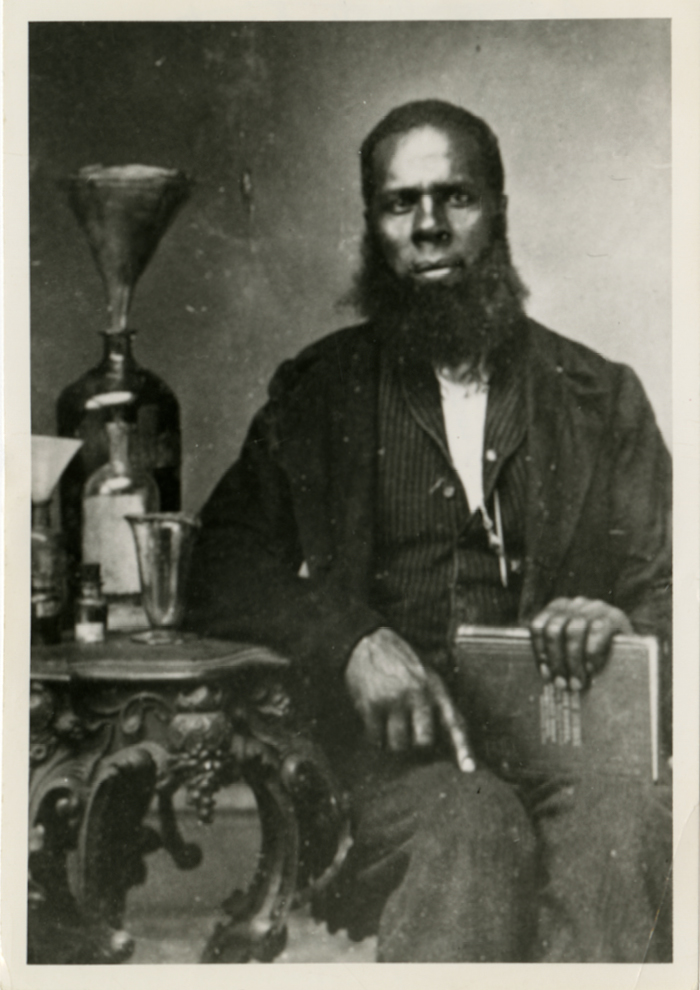

Ramey sees that tradition of preservation and experimentation at work in the writings of lesser-known figures including free black abolitionist poet Joshua McCarter Simpson (1820?–76), who wrote ironic parodies of minstrel songs, patriotic anthems, and other venerated traditions; Chicago modernist Fenton Johnson (1888–1958), who used call-and-response to experiment on Anglo-American lyric forms; and avant-garde writer and composer Russell Atkins (b. 1926), whose visual poem “Spyrytual” reassembles the traditional song “Didn’t It Rain.”

These poets are not experimenting for the sake of experiment or simply to oppose a dominant culture, in Ramey’s view. The history of captivity and enslavement sets the stakes much higher. They are “seizing workable material components from utter destruction,” and “adapt[ing] these remnants of psychic and material shrapnel of the past.” Their aim is to find authentic expression for experiences that standard uses of language stifle.

Ramey places Simpson in the earliest period of African American poetry, lasting from the arrival of the first Africans in America until emancipation. Then followed an era roughly contemporaneous with its towering poet, Paul Laurence Dunbar (1872–1906). Johnson and Atkins belong to the period of creative ferment Ramey calls the Twentieth Century Renaissances, which spans the New Negro Renaissance, the Black Arts Movement, and the midcentury era in between. The contemporary period, from the late 1970s to the present, rounds out Ramey’s account. But these are only signposts in what she wants readers to understand as an uninterrupted history.

Ramey knew a single book couldn’t be exhaustive in its selection of poets. “So I tried to do little portraits,” she says, with special attention to “people that are not necessarily looked at so closely.” Of particular note for Ramey are Harlem’s Helene Johnson and Chicago’s Margaret Danner, two overlooked 20th-century poets she finds noteworthy for their originality and craft.

Exhaustive is beside the point. Ramey’s book isn’t so much a narrative history or a survey of poets as a critical genealogy: it offers a framework for a complete and comprehensive canon of African American poetry by examining how we ended up with the truncated one we have. “A lot of figures that would have been commonly accessible in the 1960s and 1970s”—through anthologies that rarely drew camps based on differences in style—“by the ’80s and ’90s had become unknown,” Ramey says.

Her approach to retracing where the process of canonization went wrong stems from what she learned as a young literary scholar at UChicago immersed in Plato, Aristotle, and other roots and branches in the history of criticism. “That was quite formative for me in trying to say, let’s not look at individual poets in isolation. Let’s not look at a decade in isolation. Let’s try to conceive of a tradition and some functional theories of a tradition.”

A History of African American Poetry concludes with contemporary poets who, in Ramey’s view, carry on and recast this tradition’s fundamental themes and techniques. While exploring heightened complexities of voice and identity, they still insist on liberation and liberty, articulate a bond between the individual and the community, and emphasize performance and orality. And they do so with an often ironic sensibility born of being both insiders and outsiders in American culture. Across four centuries, from the earliest period to the last, Ramey observes, “progress and reclamation go hand in hand in this tradition.”