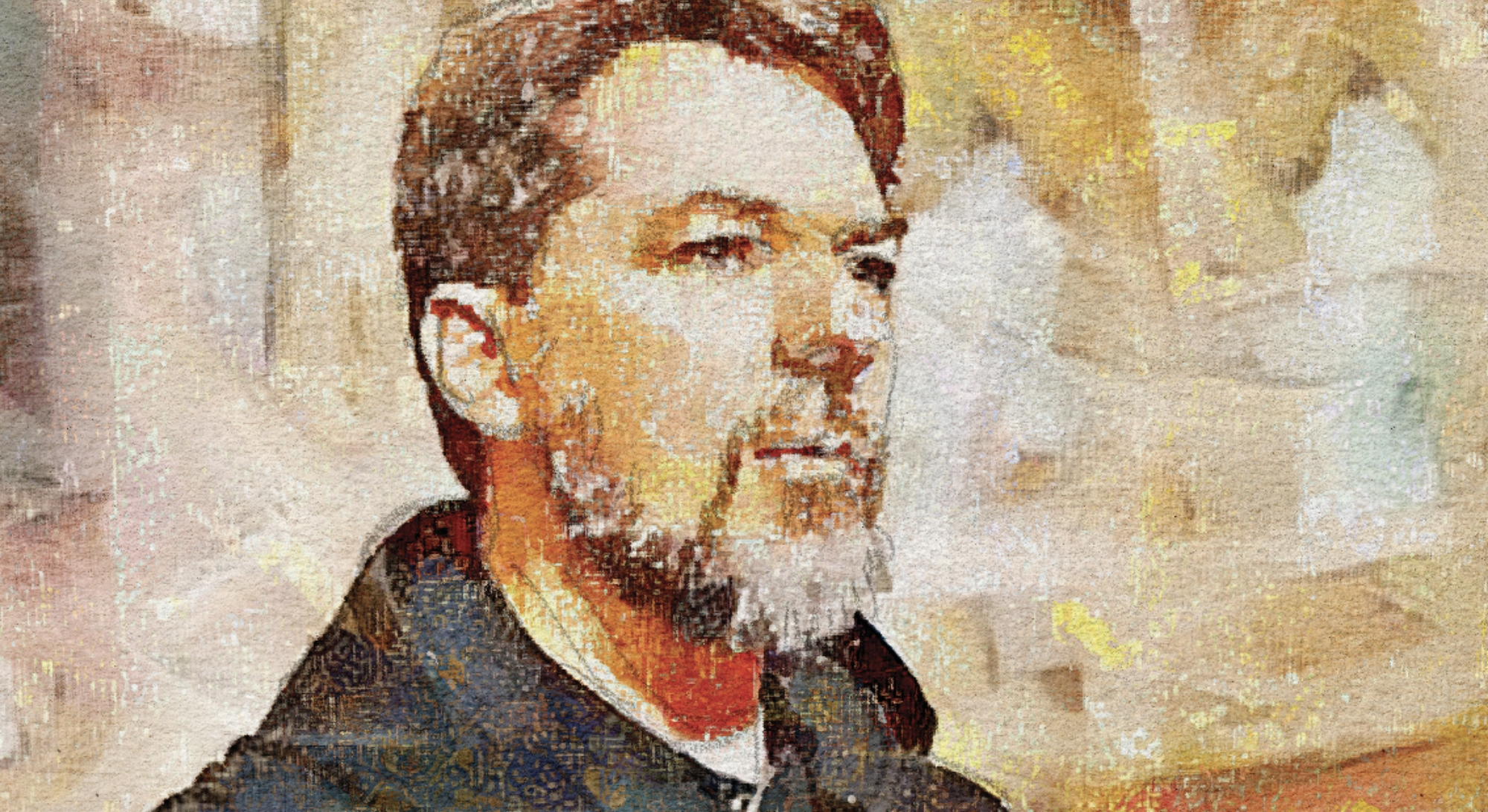

A portrait of Father Peter Funk, AB’92, by Douglas C. Anderson, AB’89, JD’92. Anderson, who serves as general counsel to the House Foreign Affairs Committee, enjoys creating art in his spare time. Like Funk, he played in a band (The Redundant Steaks) with Bert Vaux, LAB’86, AB’90, while in the College. (Portrait courtesy Douglas C. Anderson, AB’89, JD’92)

Father Peter Funk, AB’92, on life in a Benedictine monastery.

When Edward Funk, AB’92, came to UChicago as a music major, “I thought I was going to be a rock star,” he says. Funk’s band OM performed at Beat Kitchen, Double Door, Morseland, and Schubas, and had a regular slot at Phyllis’ Musical Inn. “We had a small, very fervent following,” he says, though unfortunately for the venues, “our music was so serious, people would just sit there and listen and not order beer.”

OM’s last gig was at Taste of Chicago in 1997. A few months later, Funk entered the Monastery of the Holy Cross, a Benedictine monastery in the South Side neighborhood of Bridgeport. According to its website, the monks seek God “through prayer, silence, work, and hospitality.” Funk, who was given the name Peter as a novice, is also an ordained priest. He has served as the monastery’s superior for the last 20 years.

Funk doesn’t see his choice to become a monk as a repudiation of his earlier rock-star life, but as the same countercultural impulse turned up to eleven: “The things I’m protesting against in a monastery,” he says, “are the same ones I was protesting against in a rock band.” This interview has been edited and condensed.

How was your College experience?

I enjoyed myself start to finish. I was very fortunate to have a scholarship. I’m not sure who endowed that, but I pray for him or her.

I was a serious student, but serious in the sense that I loved learning, not that I wasn’t any fun, I hope.

I reread The Rule of St. Benedict to prepare, and he says you’re not supposed to laugh. Why?

Those passages troubled me when I was first a monk. I think he recognizes that as we grow in humility, we won’t have a preference for making a lot of jokes or laughing loudly. But not in a way that precludes gentleness or hospitality. If we do laugh—if we talk at all—it’s gently and in deference to other people.

There’s also a whole section on corporal punishment. Did that trouble you?

Not that that was once practiced. As late as the 19th century, it was still a part of life in some monasteries in Europe.

On the other hand, the problem is, if one monk decides he’s not going to cooperate anymore, there’s not much you can do. You don’t have many ways to sanction him, except kick him out. But you don’t want to do that, because you want to take seriously the idea that he’s made vows to God.

It’s a conundrum. In a community our size—when you only have eight guys—you can be very vulnerable.

What’s the solution?

I’m not sure. Pray about it. And be really sober about discerning whether someone has a vocation.

I was so enthusiastic when I started. I figured monastic life would transform everybody. But there’s something mysterious about a monastic vocation. Very few people have it these days.

What did your family and friends think?

My family wasn’t super excited. I think my mother could have lived with it if I’d been a Jesuit—a professor or something like that. I have this world-class undergraduate education. How is that going to benefit me or anybody else if I go into a monastery?

But in my heart I was drawn to monasticism. To this idea of pursuing God alone.

What are the limits on your life? Could you get a beer at Maria’s [a bar across the street] or go to Movies in the Parks, for example?

We tend to stay pretty close to the cloister. Occasionally, we’ll go for a walk together for recreation, and we might stop someplace where we could get a beer. More often it’s coffee.

Once a month, we watch a movie in house. We tend to watch classic movies. We watched an Audrey Hepburn movie last Sunday night, How to Steal a Million. I would personally like to watch more foreign movies, but the subtitles are difficult for older members.

I’m very cautious about contemporary movies, because it’s not very healthy for monks who are trying to live a life of peace and celibacy. We watched Father Stu last year. Mark Wahlberg plays a boxer who becomes a priest, and there’s a lot of profanity. Occasionally, we’ll watch a fantasy action movie like Mission Impossible.

How did you come up with the name OM for your band? Were you into Eastern religions?

We were supposed to play the Battle of the Bands at the Shoreland, and we didn’t have a name. One of the guys, who is now a fellow at King’s College, Cambridge [Bert Vaux, LAB’86, AB’90], had just finished a Sanskrit class. And he said, “Why don’t we call ourselves OM?” I liked the idea that if one chants the syllable properly, one harmonizes with all sounds in the cosmos.

The way we talked about it is, we wanted to make music that was not only musically good, but morally good. Toward the end of the band, the more we explored this, the less we sounded like a rock band.

Were OM’s lyrics about religion?

Generally spiritual themes, but not overtly religious.

It’s no surprise that I would enter a religious order that’s so imbued with music. We sing two or three hours a day, just gloriously beautiful music. There’s so much incredible chant in the Church’s tradition. It’s a privilege to be a part of it. I find it amazing that we are chanting roughly the same melodies and the same words that some monk in Germany in 1100 was chanting.

Do you have to sing well to join a Benedictine monastery?

Not everybody’s a great singer in the monastery. We drown them out.

What’s the hardest part of being a monk?

I think I’m particularly well suited to the life. But obedience is definitely the hardest part. For everybody.

To have a really disciplined way of discerning God’s presence is a challenge today. I think it was easier 300 years ago, probably a lot easier 800 years ago.

What brings you the most joy?

The great privilege of being able to spend a lot of time in prayer every day.

What could we learn from your way of life?

During COVID, we had all kinds of things to tell people. Most people were not used to being stuck in the house with everybody all day. Well, we do this by choice. Here’s what not to do.

So that kept me going for a while on our blog.