With its hand-tinted art deco graphics, this lobby card for Wolf Song (1929) catalyzed Cleveland’s collecting passion. (All images courtesy Dwight M. Cleveland, MBA’87)

Dwight M. Cleveland, MBA’87, collects film posters with an eye for high art.

When Dwight M. Cleveland, MBA’87, sees a film poster that has ascended from advertising to art, “it’s just really kind of a visceral thing,” he says. “Most of the stuff that I buy, it’s like a chemical reaction when I see it.”

That deep-seated intuition goes back to his earliest days as a collector. He was a senior at Brooks School in North Andover, Massachusetts, when an art teacher who collected posters returned from a buying trip with something special. In a stack of lobby cards, the smaller-scale advertisements that once greeted moviegoers inside cinemas, Cleveland saw a portrait card for Wolf Song, a 1929 silent film starring Gary Cooper and Mexican actress Lupe Vélez. The image, he says, “just screamed out at me, ‘Take me home.’ I had to own this thing. I loved it.” He could only get it by offering an acceptable trade. So with his teacher’s want list in hand, he spent the next eight months during a gap year in Los Angeles acquiring posters that won him Wolf Song.

We’ve stepped into the kitchen of Cleveland’s Lincoln Park home, an Italianate row house he restored in the early 1980s. Since graduating from Chicago Booth, Cleveland has run a Chicago real estate company that does historic renovations of homes like this one. Vintage fixtures and décor, like the art nouveau chandelier inside the front door, hearken back to the home’s post–Great Chicago Fire era.

Cleveland gathers these pieces before they become impossible to find, as with many of his prized posters. Never sold to the public and never meant to outlast local theatrical runs of the films they advertised, the ephemera Cleveland collects live on the edge of loss. “If an image haunts me a little bit,” he says, “then I know that I should own it.”

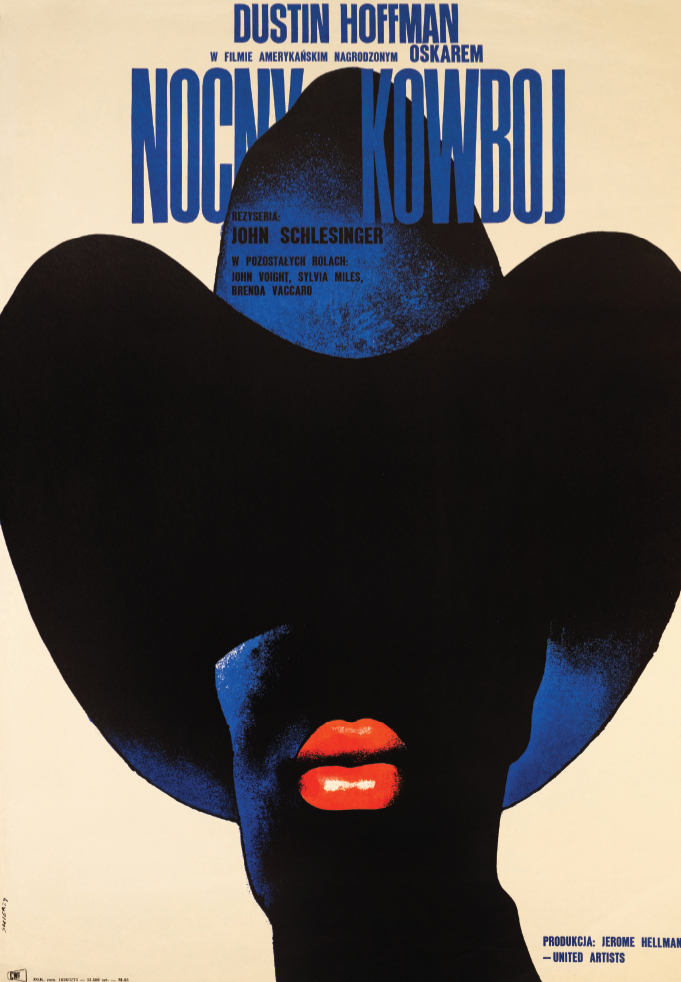

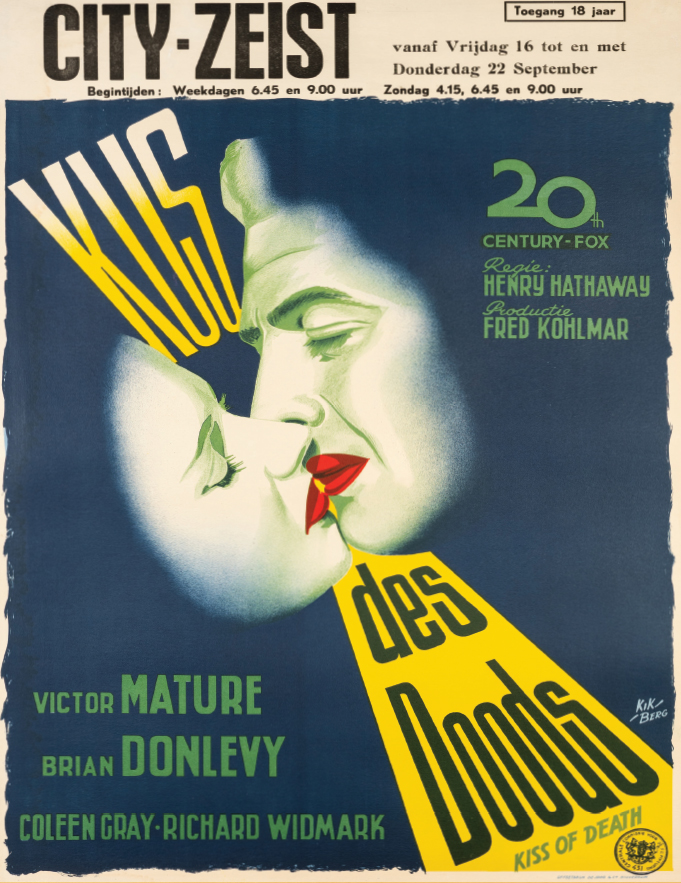

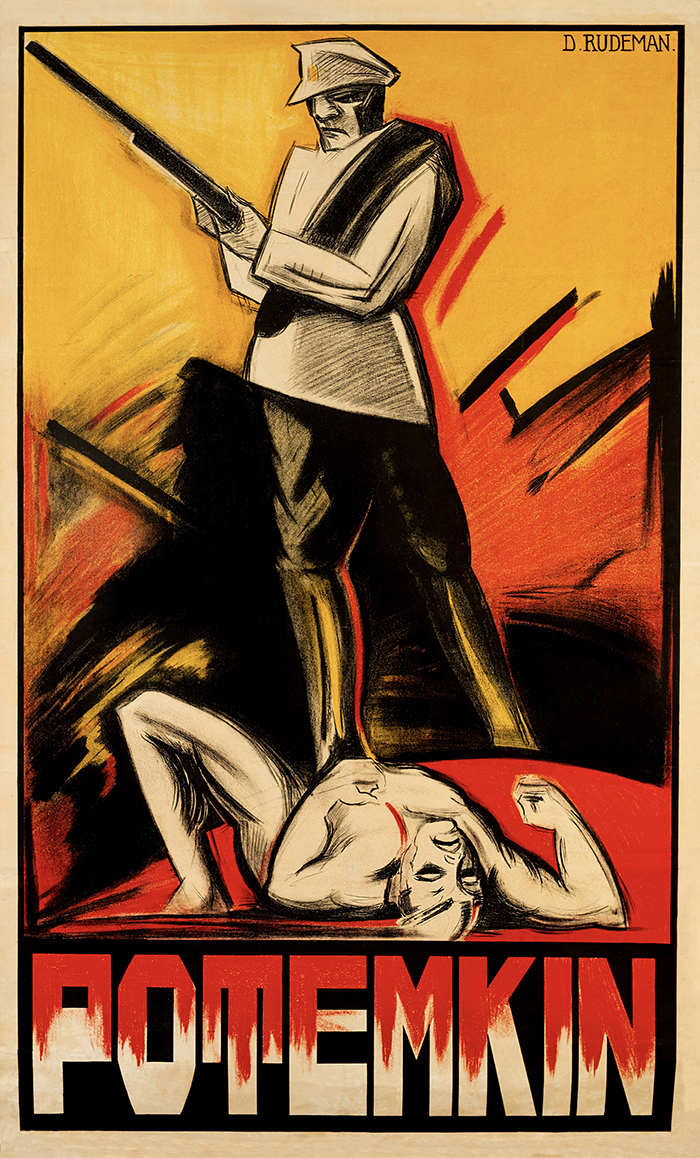

For Cleveland, the art of the film poster, like the art of collecting, comes from maximum concentration. Poster artists “captured the soul” of the films they represented, he writes in his 2019 book Cinema on Paper: The Graphic Genius of Movie Posters (Assouline). “The best posters in my mind,” he continues, “are those that reduce the entire essence of a movie into a single, vivid sheet.” Cleveland has distilled his collection to 3,500 works on paper that meet this high aesthetic standard. (He amassed a separate archive of 45,000 posters, all of them now sold or donated, for their historical rather than artistic value.) The culled pieces are Cleveland’s argument that film posters belong in the worlds of both commercial and fine art. They were the basis of a major exhibition last year at the Norton Museum of Art in West Palm Beach, Florida, the largest-ever museum show of film posters and a landmark for the art form.

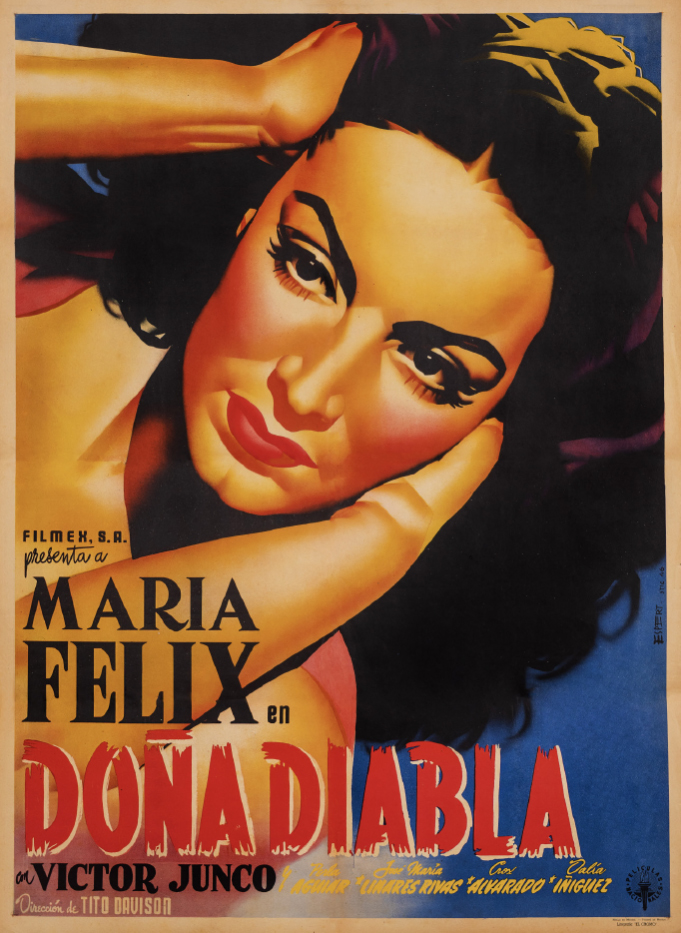

Reaching from the earliest days of cinema to the 21st century, Cleveland’s collection is exceptional for its international scope. “I’ve been to every continent other than Antarctica hunting this stuff down,” he says. For more than 40 years he’s traveled regularly to France, where illustrator Marcellin Auzolle created perhaps the world’s first film poster in 1895 for the Lumière brothers. He took his search to Italy in 1985, finding posters by such celebrated artists as Luigi Martinati and Angelo Cesselon. In the 1990s he became an early collector of Japanese posters, some with distinctive two-panel designs, and a trip to Cuba that same decade deepened his focus on Latin American works. In 2017 he donated more than 1,000 Argentinian posters to the University of Texas at Austin, one of the institutions that he’s found share his collecting interest.

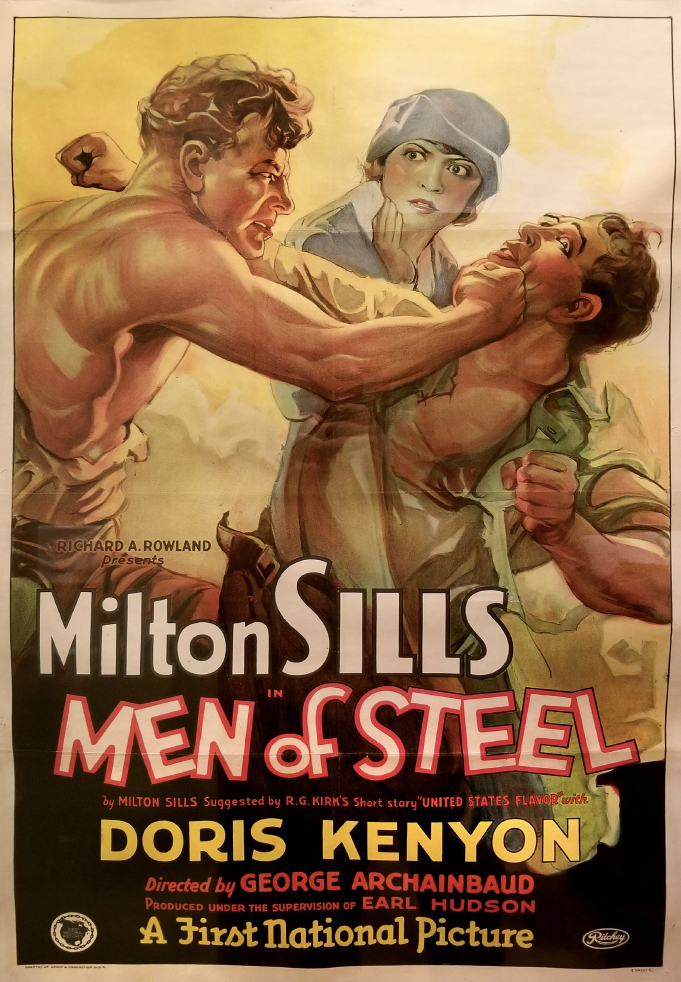

In an early find closer to home, Cleveland gained insight into the romance that inspires collectors and keeps the posters themselves alive. Not long after his Wolf Song days, Cleveland received an ad response from a Minnesota woman with a box of 27 film posters. She had received them from a movie theater employee who courted her in high school. He was one of the people Cleveland calls the “first curators” of film poster art. “He wanted to romance this woman,” so he saved a special selection of the hundreds of posters Cleveland figures he would have handled at the theater in the late 1920s—including a vibrant stone lithograph poster, one of two known surviving copies, for the lost 1926 silent film Men of Steel. “He was like a great art critic,” Cleveland says. And her stashing them away for decades was part of the miracle collectors like Cleveland depend on. “It’s completely an act of God that these things survived.”