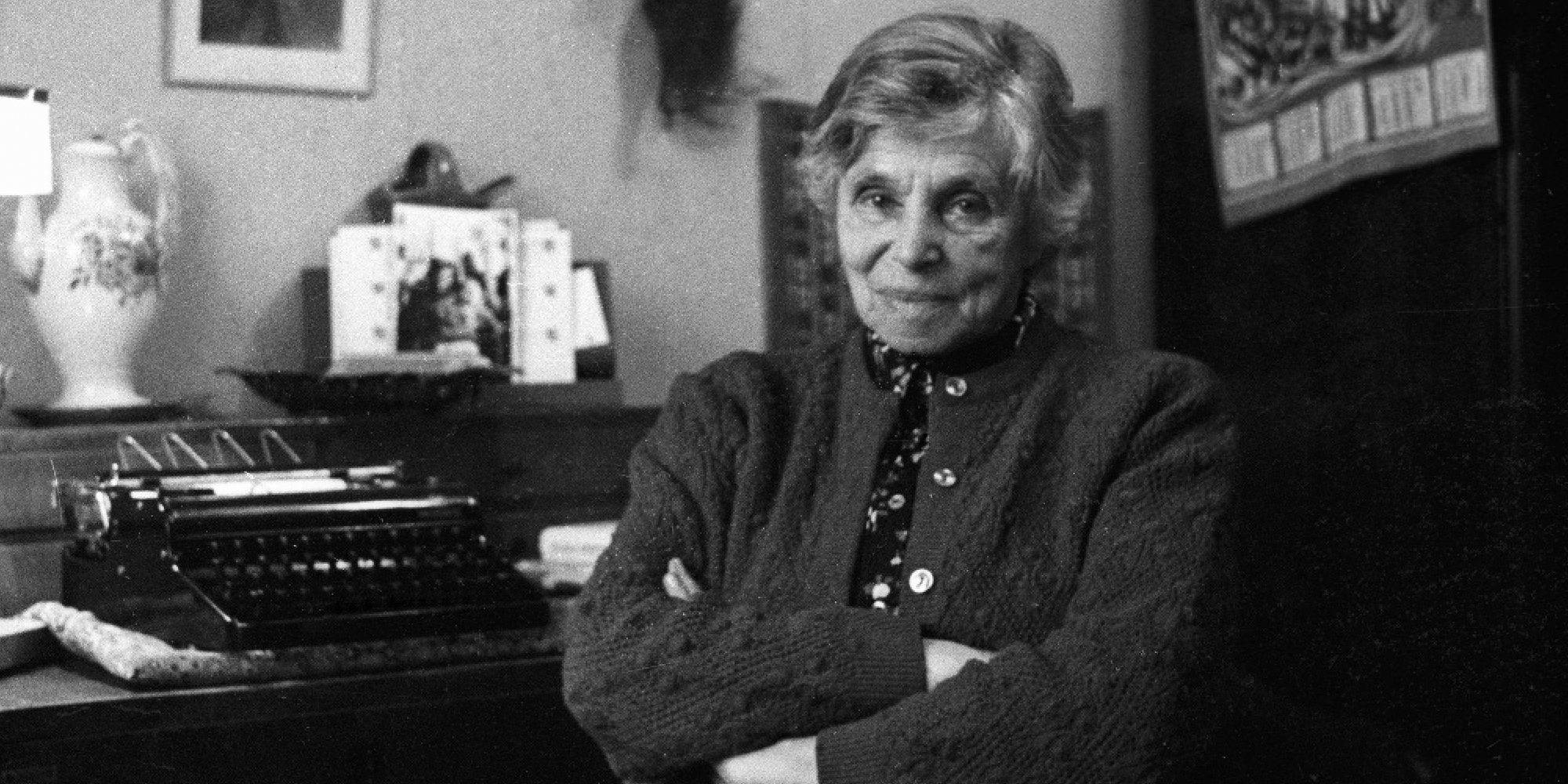

Rita Rait-Kovaleva, whose Russian translation of The Catcher in the Rye became a best seller, also brought the works of Kurt Vonnegut, AM’71, to Soviet readers. (SPUTNIK/Alamy Stock Photo)

How Soviet citizens made Western culture their own.

In 1960, seven years after the death of Joseph Stalin, readers in the Soviet Union met Holden Caulfield for the first time. They were electrified. In Holden’s story, Soviet citizens found language for their experiences. As one fan put it, “Which one of us, Russian readers, did not think of school as ‘duratskaia,’ of classmates as ‘kretiny,’ of lessons as ‘pokazukha’?”—stupid, bastards, phony. The Russian translation of J. D. Salinger’s 1951 novel The Catcher in the Rye became a Soviet literary sensation, prompting multiple reprintings.

The Catcher in the Rye arrived in the USSR among thousands of Western cultural works during the “thaw,” a period of relative openness following Nikita Khrushchev’s rise to power. This wave of officially sanctioned imports, more diverse in style and subject matter than what had come before, made its way to the far reaches of the country. Why and how Western cultural objects arrived, and what they came to mean to ordinary Soviets, is the subject of UChicago historian Eleonory Gilburd’s book To See Paris and Die: The Soviet Lives of Western Culture (Harvard University Press, 2018).

To many Soviet citizens, who encountered American and European books, films, and TV shows all the time, these materials didn’t feel entirely foreign. Western imports were “an inseparable part of Soviet life,” Gilburd says, both Soviet and non-Soviet at the same time. By examining how Western culture was seamlessly incorporated into everyday life, Gilburd, AB’98, now an assistant professor of history at UChicago, hoped to understand how the thaw’s distinctive culture came to be.

The book interweaves the experiences of three groups: the bureaucrats, who brought Western cultural material into the country; the mediators, such as literary translators, dub actors, and critics, who helped make that material accessible; and the public. In different ways, all three took part in the work of translation, which Gilburd sees as “a mechanism of transfer, a process of domestication, and a metaphor for the way cultures interact.”

Literary translators sought to capture “not the text itself, so much, but what they called the reality behind the text,” Gilburd says—how it made readers in its country of origin feel. This resulted in translations that seem interventionist by contemporary standards. In The Catcher in the Rye, for instance, American Holden repeats words like “terrific” and “goddam”; Russian Holden employs a raft of synonyms. That subtle difference changes how the character comes across, making him, in Gilburd’s view, appear more sensitive and vulnerable. When it came to cinema, dubbers added voice-over narration and even inserted Russian billboards and signs into Western films. It’s not surprising that viewers sometimes didn’t know what was foreign and what was domestic.

One outcome of the domestication of Western materials, Gilburd argues, was that they took on unexpected new meanings in the Soviet context. Ernest Hemingway’s For Whom the Bell Tolls, about the Spanish Civil War and idealism pushed too far, was read as alluding to the violent, repressive Soviet Union of the 1930s. The Catcher in the Rye became enmeshed in Soviet literary debates about whether slang and other forms of youth language belonged in print.

There is no single explanation for why certain Western imports flopped and others became classics. (A translation of The Grapes of Wrath failed to capture much interest, perhaps understandably—after decades of Soviet realism, who wanted to read another novel about workers’ struggles?) But one notable area of audience interest, Gilburd writes, was fiction centered on emotion—something that had largely been left out of Soviet culture in the 1930s and ’40s, when straightforward depictions of proletarian triumph proliferated.

By the 1950s, Soviet artists and critics had begun to worry about the bloodless quality of domestic art. After all, they reasoned, even in a society of perfect economic equality, heartbreak and other forms of personal pain would still exist.

Western art helped fill the gap, providing language and images for what had gone unspoken and unseen. One enthusiastic reader of Erich Maria Remarque credited the German novelist with “[telling] us, young Soviet men and women, about these feelings” of “eternal, singular, and unique” love. Western films offered franker depictions of sexual behavior than Soviet viewers had ever seen before—an offensive experience for some, who felt the country’s censors were not doing their jobs, but revolutionary for others.

Gilburd’s book concludes with a somber chapter on Soviet emigrés and their lives in the countries they had only known from movies and books. The reality, inevitably, was more painful and complicated. She goes on to compare the emigré experience to life in post-Soviet Russia, when the country, as a whole, “essentially emigrated to the West.”

In the tumultuous 1990s, former teachers, doctors, and engineers, their savings wiped out and lives upended, sold their possessions on the street. They peddled World War II medals to tourists but found no takers for their idiosyncratic translations of Hemingway, Remarque, and Salinger. With the end of government control over information, new and unmediated depictions of Western life flooded into the country, rendering what was once beloved suddenly pointless.