Amanda Williams, LAB’92, used a re-created blue pigment developed by George Washington Carver in this recent work. (Installation view: Amanda Williams: Run Together and Look Ugly After the First Rain, Casey Kaplan, New York, February 28 – April 26, 2025. Photo: Dan Bradica Studio.)

An alumna artist and a team of UChicago chemists revived a century-old recipe for blue pigment.

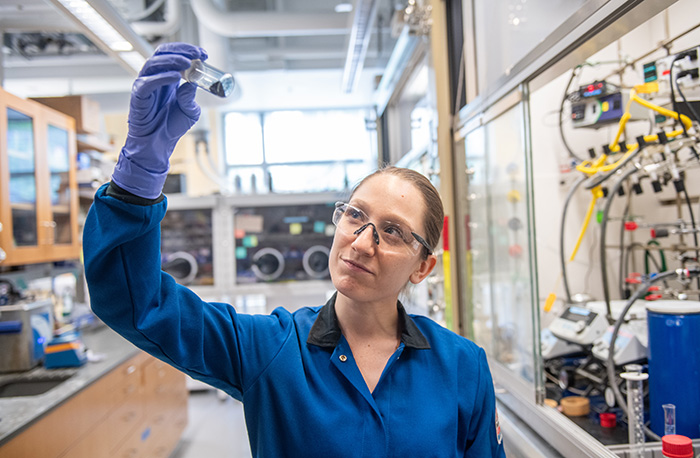

In a University of Chicago lab, chemist Amanda Brewer pours two clear liquids together in a beaker. Instantly, almost magically, the contents turn a rich blue.

Once one of the most difficult colors to capture in paint, blue was available to pre-19th-century artists only by grinding up the prized stone lapis lazuli. By the 1900s blue was still difficult enough to produce that inventor George Washington Carver received a patent for his process in 1927.

Carver’s method had been largely forgotten when, nearly a century later, artist Amanda Williams, LAB’92, stumbled across it. Fascinated by both the method and its creator, she decided to re-create his formula and reached out to chemists at the University of Chicago for help.

“The synergy of those brains and points of view overlapping constantly was really interesting to see,” Williams says of working alongside UChicago scientists and students. “There has to be some discipline, but there also has to be a little bit of risk. Innovation has to be a little bit of both of those things.”

Williams is in love with color. The artist, architect, and 2022 MacArthur fellow credits this early fascination to growing up when Black first became prevalent as a racial term. Since then she’s been struck by the multifaceted nature of color—as material, as racial signifier, as emotion.

In her Color(ed) Theory series a decade ago, Williams painted abandoned buildings on Chicago’s South Side in hues significant to the Black community—colors inspired by things like Pink Oil Moisturizer hair lotion and Flamin’ Hot Cheetos. The series’ cheeky humor celebrated cultural experiences many Black Americans share even as it highlighted systematic erasure and urban disinvestment.

Williams first came across Carver’s hue while conducting archival research into Reconstruction-era patents. “What did Black people make when they didn’t have to just think about survival?” she wondered.

When a friend mentioned that Carver held a patent for blue pigment, Williams was shocked. “I said, ‘The peanut man?’”

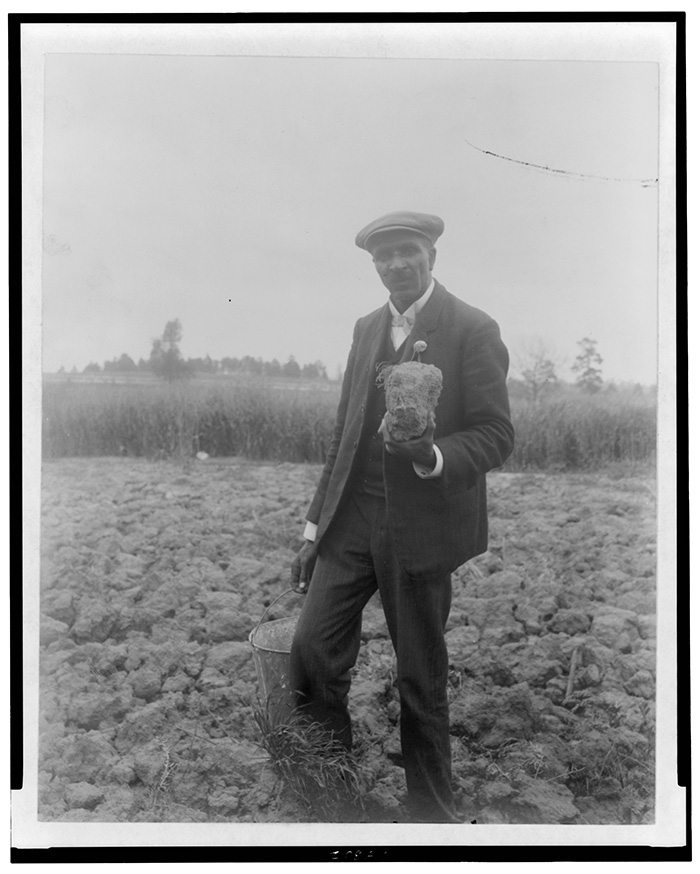

More digging revealed that Carver, a Tuskegee University professor, held only three patents with the US government, despite being a prolific inventor (including of uses for peanuts). One of those patents was for making blue pigment from iron-rich clay.

“He was using this Alabama red clay, which is in abundance in the soil on Tuskegee’s campus,” Williams says. “This idea of one of your source materials being free seems to reinforce a hypothesis that this is why the patent was necessary, because he was going to streamline the production.”

Williams thought, “Why not try to re-create it?” However, Carver’s process would prove more complicated than simply following a formula: Some parts were intentionally vague to protect the patent.

During a chance meeting at the opening reception for the Smart Museum of Art’s Monochrome Multitudes exhibition in 2022—another celebration of color—Williams mentioned the project to University President Paul Alivisatos, AB’81.

“We’d love to help,” Alivisatos said.

When Brewer first saw the original 100-year-old patent, she remembers shaking her head. The formula calls for large quantities of very concentrated acids mixed together for months at a time.

“I was like, ‘Oh my god, we’re not doing it in this exact form, just for safety reasons,’” says Brewer, a postdoctoral scholar in Alivisatos’s lab. “[Carver] must have been doing this outside, because it’s going to create fumes for months.”

Over the summer of 2023, Brewer, with the help of three students—Sarah Thau, Class of 2026; Nathan Berhe, AB’24; and summer researcher Nadia Ceasar—adapted Carver’s formula to make it safer and more manageable.

The formula calls for separating the iron from clay using strong acids. Then the iron is mixed with other reagents, and the blue precipitates out—appearing dramatically from a combination of two yellowish solutions.

Experimenting with various soils, including jars of Alabama dirt sent by a cousin of Williams’s, the team consolidated the formula to use just one type of acid. They also took advantage of modern equipment like centrifuges (normally used in the Alivisatos lab to isolate quantum dots) to more quickly separate out components.

By the end, the team had a reliable formula that could be achieved in hours rather than weeks or months.

To investigate the crystal structure of the blue pigment, Brewer tested samples using a technique called powder X-ray diffraction. Interestingly, Carver’s creation was chemically identical to Prussian blue, one of the first pigments achieved through modern chemistry, which caused a sensation when it was accidentally invented in the 1700s.

Curious about what kinds of clay could work, the team also tested Carver’s formula on soil from Bronzeville, a historically Black neighborhood in Chicago, and from the University of Chicago campus. All produced the same startling blue.

For Thau the experience was “the best project I could have hoped for as an undergrad,” she says. “It was so incredibly cool. And I notice color and pigment much more now. It’s around you all the time. It crops up in the oddest places. You’re painting your nails, or seeing a blue car on the street and wondering how that pigment works.”

There is one other lasting consequence too. Some parts of the chemistry lab are now permanently stained blue.

With the formula in hand, a German manufacturer was able to scale up the process and produce 100 pounds of pigment for Williams’s studio so that she could begin to experiment with the next step: turning the pigment into paint. Paint requires a binder to help the pigment adhere to the surface being painted; Williams decided on milk, which is what Carver would likely have used.

Last year, for the New Orleans arts triennial Prospect.6, Williams used the paint to coat two buildings in Carver blue: an arts building at Xavier University and a shotgun-style house on the campus of the New Orleans African American Museum.

Williams wanted the structures to serve as a pop of joy amid the already color-saturated city. She also wanted to highlight Black ingenuity.

“The level of effort Carver must have had to endure to even receive the patent was a testament to innovation and perseverance,” Williams says.

Williams continues to experiment with the pigment in her work. She recently opened a solo exhibition in New York City titled Run Together and Look Ugly After the First Rain, a collection of 20 paintings and 10 collages using paint she created from the Carver blue pigment.

“George Washington Carver wanted to make sure knowledge extends itself, that it builds on a network of people learning from each other,” Williams says. “So it’s been really nice that the project, in some ways, embodies that at its elemental level.”