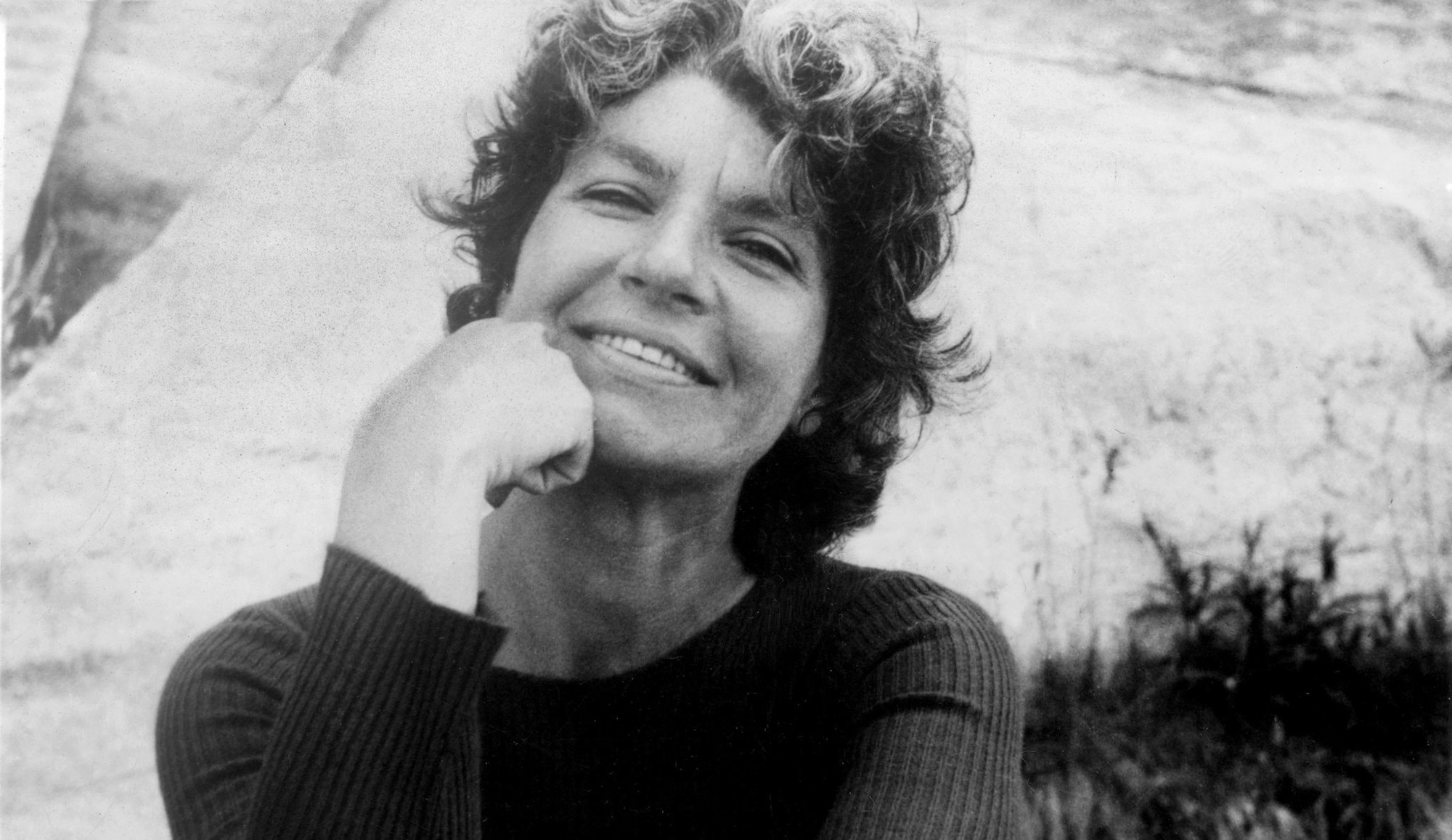

(Photography by Jacob Howland)

The Hyde Park Book Club discusses Howland’s 1974 novel W-3 and Bette herself.

The February meeting of the Hyde Park Book Club—on Zoom, like everything during the pandemic—begins with a slideshow.

There’s a black-and-white photo of Bette Howland, AB’55, middle-aged, smiling, her chin resting on her fist.

Then headshots of her sons, whom we met as little boys—one dark, one blond—in the pages of Howland’s bleak memoir W-3 (Viking, 1974). The older son, Jacob, his dark hair now salt and pepper, is emeritus professor of philosophy at the University of Tulsa. The younger, Frank, still sandy blond, is professor of economics and leadership at Wabash College in Indiana.

Next comes a photo of New York editor-publisher Brigid Hughes of A Public Space Books—like Bette, in arty black and white, chin on fist—who rediscovered Howland and introduced her to a new generation of readers.

“In 1968,” reads the next slide, “Bette Howland, a divorced single mother of two boys and a struggling author, took an overdose of sleeping pills and was admitted to the University of Chicago psychiatric ward (W-3). W-3 is a memoir of her experience, originally published in 1974 and newly republished in 2021.”

The final slide highlights Bette’s years in Hyde Park: as an undergrad in the early ’50s, she worked as “an au pair of sorts.” In the late ’60s she lived at 56th and Dorchester; Jacob and Frank attended Ray Elementary. From 1993 to 1996 she taught in the Committee on Social Thought.

“Welcome,” says Michal Safar, MBA’77, one of the coordinators of the Hyde Park Book Club, as the slideshow concludes and the screen fragments into a five-by-five grid of faces. It looks like one of those verification tests to prove you’re human: click on the squares that include bookshelves. About a third of them do.

Frank Howland speaks first, adding more depth to the slideshow’s biography: “Not surprisingly my mother loved books and read very widely,” he says, reading from prepared remarks. “But she also loved music, art, architecture, and theater. Among her favorite writers were James Fenimore Cooper, Stendhal, Dickens, Dostoyevsky, Tolstoy, Hardy, Stephen Crane, Henry James, Joseph Conrad, D. H. Lawrence, Theodore Dreiser, William Faulkner, and Primo Levi. … She adored Bach’s cello suites and Schubert’s piano sonatas; loved the Missa Luba, a Latin Mass sung in Congolese style; and was a big fan of Joan Baez and Odetta.”

In her writing, Bette returned again and again to “the people who live on the margins in Chicago—the poor, the old, and the sick—and her family,” Frank continues. “I wasn’t around in the 1940s and early ’50s, but I can say that the portraits she paints of the family in the 1960s and ’70s are dead on.” Jacob, in his square on the opposite side of the screen, smiles and nods knowingly.

While Frank covered the biographical, Jacob focuses on the literary. Bette’s description of the psychiatric ward in W-3, he says, “is the language of myth, of the soul’s journey through territories of ultimacy … a region between life and death.” The structure of the book “has something of the ring structure of ancient epic.” By the end of her stay there, “she finds some saving knowledge and draws from the common stock of myth and literature to fashion her indigenously American, Chicagoan, working class, and female voice.”

Then it’s Brigid Hughes’s turn. Hughes, whose imprint A Public Space Books reissued W-3 in January, first discovered the book in the dollar bin of a secondhand bookshop. In Hughes’s Zoom background, that hardback copy, with its lurid green ’70s lettering, rests on top of her bookshelf on the left; the new hardback edition is on the right. “It feels somehow appropriate to be meeting Bette Howland not directly,” she says, “but through the people she knew and who were important to her.”

Hughes reads the passage from W-3 that first caught her attention while flipping through the dollar-cart copy: “All I knew was this: I couldn’t take it anymore, no longer could bear this burden of concealment. Things seemed bad enough without adding extra weight. I wanted to be rid of it all, all of it. I wanted to abandon all this personal history—its darkness and secrecy, its private grievances, its well-lit sorrows and prides—to thrust it from me like a manhole cover.”

When Howland first published W-3, many reviewers remarked upon “how little of her there is in the book, and how much of it is her looking at others,” Hughes says. This unusual approach for a memoir was another reason she was drawn to the book.

The discussion opens up to the broader group. “I worked in the psychiatry department at the University of Chicago in the middle ’60s, but in outpatient psychiatry,” says Joseph Marlin, AB’54, AM’60. “I did not know her. But I do know that many patients at that time stayed in as inpatients much, much longer than they do now. The standard used to be 120 days, which is almost unthinkable.” The fact that Howland remained in the ward for so long, he suggests, “gave her an opportunity to exercise her perceptions.”

Among tonight’s attendees are several people who did know Howland. “I was just checking in W-3 to find the part that I was in,” says Ruth Knack, AM’70. She and a classmate from graduate school had visited Howland in the hospital. (“They looked as though they had some official status; social workers maybe, or medical students—two pretty, bright-faced, confident young women in short skirts, sandals, with sunburned cheeks,” Howland wrote. “I was proud of my fine visitors.”)

Their portrayal in the book was not negative, Knack says. “We had no nicknames, nothing like the other people. We were kind of stuck in there, and I’ve never really known why.” She appeals to Jacob and Frank: Did their mother ever explain? Do they have theories?

“I’m pleased that you outed yourself, Ruth,” says Jacob. Both laugh. He offers his interpretation: “The whole point of the scene is this contrast between who she was—you’re her friends, she identifies with you, you’re graduate students—and then where she was. She’s always standing between two worlds.”

Later in the discussion, Dottie Jeffries, also one of the book club coordinators, adds her own recollection: “I met Bette in Union Pier, Michigan, in the company of Ruth Knack. One of the things that always struck me was the fondness she had for her grandchildren. She just would get illuminated talking about them.”

“She left Chicago a few years after the events of W-3 and never really lived there again,” Hughes notes. (Howland, who divorced in her twenties and never remarried, moved often, settling in a series of isolated places: an island in Maine, rural Pennsylvania, a Quonset hut near the lake in Michigan, a farm in Indiana.) “Do you know why she left?” she asks Frank and Jacob. “Did she ever think about coming back?”

“She was pretty portable. She didn’t have a lot of stuff,” Jacob says. “She would make her nest everywhere she moved. She loved to cook, made her own yogurt. She was superfit—would always do yoga and swimming. I’m not sure she felt completely settled anywhere.”

“She really liked beautiful places,” says Frank. “She most liked Lake Michigan. She enjoyed walking along the beach every part of the year.” When she moved somewhere new, “she had no trouble making friends.”

Neither one has memories of the time their mother spent in W-3. Frank’s recollections of that year, 1968, include the Democratic National Convention and that their grandfather, Bette’s father, was stabbed in the back on the street and then just walked home. “He had a fairly fleshy back,” he notes. (Jacob dissolves in laughter.) But of his mother’s illness, Frank says, he remembers nothing.

“We had a strong relationship with her,” Frank adds. “She didn’t believe in sidelining children. She didn’t believe that you needed to lose to children in games.” Jacob is laughing again, leaning back in his chair.

“I remember one day she taught us to play poker,” he continues. “Our grandparents arrived in the apartment—this is in Uptown—just at the moment when I burst into tears because my brother had bluffed me out of my little hoard of pennies. My grandparents were appalled.”

“That’s right, I remember that,” says Jacob. “And I’ve been bluffing ever since.”