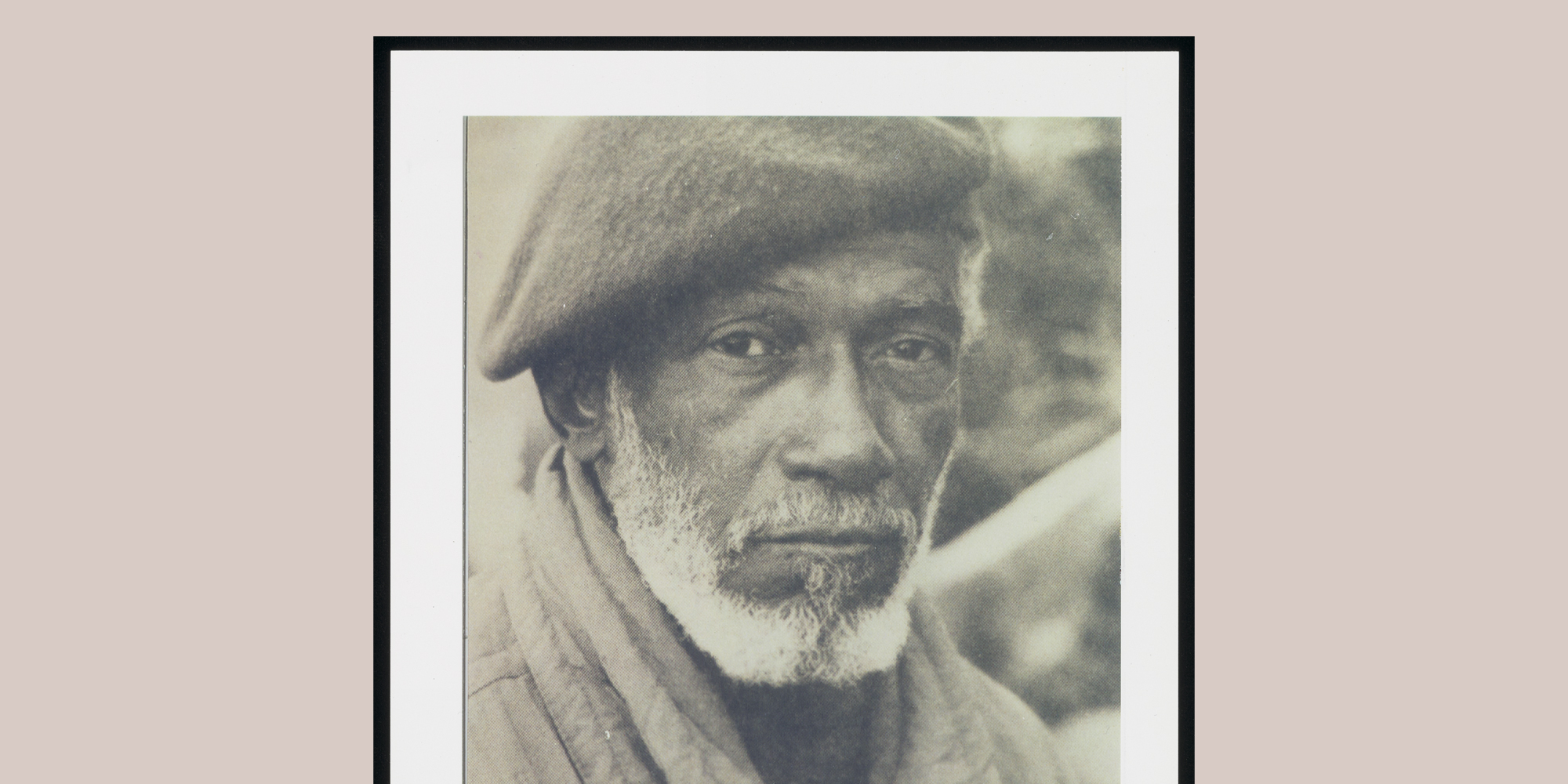

Author Sam Greenlee, EX’57 (shown here in an undated photo), cowrote and coproduced the 1973 film adaptation of his signature novel, The Spook Who Sat by the Door (Photo courtesy Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation, River Campus Libraries, University of Rochester)

Sam Greenlee, EX’57 (1930–2014), distinguished himself as a Foreign Service Officer, then found his true mission as a radical writer.

Sam Greenlee described the title of his first and best-known novel, The Spook Who Sat by the Door, as more than just a double entendre. The 1969 thriller, about the first Black agent recruited to the Central Intelligence Agency, gives titular hero Dan Freeman a moniker familiar as both a racial epithet (“because we’re supposed to be scared of ghosts,” Greenlee said) and a slang term for intelligence agents (“because they’re supposed to be invisible”). But his sardonic wordplay, Greenlee insisted, had a third layer of meaning: “that an armed revolution by Black people haunts White America, and has for centuries.”

Greenlee, EX’57, wrote the best-selling novel—which later became a cult-classic film—after spending eight years in the US Foreign Service. In his tale of subversive infiltration, the protagonist enters the CIA through a racial integration program launched at the behest of a US senator with an ulterior political motive: to shore up reelection support from Black voters. The statesman finds “a fresh, dramatic and headline-capturing act,” Greenlee writes, in castigating the CIA for having no Black officers. When the agency institutes a special training program for prospective Black officers and Freeman becomes the lone recruit to make it through the course, he is named chief of the top secret reproduction section, a glorified clerical position.

Playing the part expected of him, he rises to the rank of special assistant to the director, with the responsibility “to be black and conspicuous”—that is, to sit by the door—“as the integrated Negro of the Central Intelligence Agency of the United States of America.” Secretly, Freeman is becoming “the best undercover man the CIA had.” He gathers intelligence and acquires experience that he ultimately takes back to his native Chicago, where he resumes his career in social work as a cover for the plan he’s had all along: to organize the city’s street gang members into a force he hopes will stoke a countrywide militant uprising.

“If the idea makes you pale,” wrote a Chicago Sun-Times reviewer in 1969, “you are probably pale to begin with.”

Though his novel no doubt shocked some audiences, Greenlee seems to have been neither subversive when he belonged to the Foreign Service nor secretive about his attitudes when he left. He served with distinction in the US Information Agency from 1957 to 1965, one of the first Black officials in the USIA.

Over time he grew disenchanted with Foreign Service work and wanted to pursue writing full time. When the US State Department canceled a tour by Duke Ellington, deeming “hot jazz” inappropriate for the planned concerts honoring slain president John F. Kennedy, the catalyst was set. “I said, ‘I’ve got to get out of here,’” Greenlee remembered. “‘These people have shown me exactly what they think about Black people.’”

Still, the self-described former propagandist took from his government service what he called “intensive training” for his work to come as a novelist and filmmaker. On leave in Chicago in 1965, he watched as the Watts riots broke out in Los Angeles and thought, based on his service overseas, that such rebellions were bellwethers of more organized revolutionary activity.

After leaving the USIA, Greenlee and his Dutch-born first wife, Nienke “Nina” de Jonge Greenlee, moved to the Greek island of Mykonos, where he wrote The Spook Who Sat by the Door in one summer. He sustained his writing life in Greece for a period in the 1960s partly by going to mainland clubs and singing the blues for tips.

That was one skill Greenlee had picked up at home rather than abroad. Born on Chicago’s South Side in 1930, Greenlee grew up in the Washington Park and Woodlawn neighborhoods. His mother was a dancer, singer, and actress; his father worked on the Santa Fe Railroad and was later maître d’ at the Cliff Dwellers Club. Greenlee’s neighborhood around 63rd Street and St. Lawrence Avenue was a “striver’s community,” he told the HistoryMakers oral history project in 2001. “It was understood that I would get an education,” Greenlee said. And, because his family couldn’t afford to send him to college, “it was taken for granted that I would figure out some way to do it on my own.”

Greenlee attended the University of Wisconsin–Madison on a partial track and cross-country scholarship, graduating with a degree in political science in 1952. At a Stagg Field track meet, UChicago track coach Edward “Ted” Haydon, LAB’29, PhB’33, AM’54, suggested that he apply for graduate school and run track at the University. Greenlee studied international relations in the Social Sciences Division from 1954 to 1957. While in Washington, DC, and looking for a government job to support him while he finished up his graduate thesis on Vladimir Lenin, he was recruited to a junior officer training program that led him to the US Information Agency. “A year later I was caught up in the Baghdad revolution,” Greenlee said, “and writing a thesis was the last thing on my mind.”

At the University of Chicago, Greenlee had reveled in the intellectual pluralism of the campus culture. The University in the mid-1950s, as Greenlee remembered it, “had an almost equal group of right-wingers and leftists. And we were constantly clashing. It was marvelous for that reason,” he said. “You know, to be exposed to the total spectrum of political thought.”

Tenacity in the midst of clashing viewpoints prepared Greenlee well for the battles ahead over The Spook Who Sat by the Door. Between 1966 and 1969, the novel was turned down more than 40 times by publishers. Unable to find an American publisher willing to go near the incendiary subject matter, Greenlee had better luck in London. Allison & Busby, an upstart independent press cofounded by the Ghanaian-born British editor Margaret Busby, released the novel in a 1969 UK edition that made the best-seller lists and earned book-of-the-year mentions in two of London’s major newspapers.

The book’s success in London brought it to the attention of New York City publisher Richard W. Baron, who issued an American edition under his own imprint later in 1969. For critics, the book was dynamite—in more senses than one. “The reader should be cautioned to remember this is a work of fiction and not a statement of fact,” read a favorable review in the LA Sentinel.

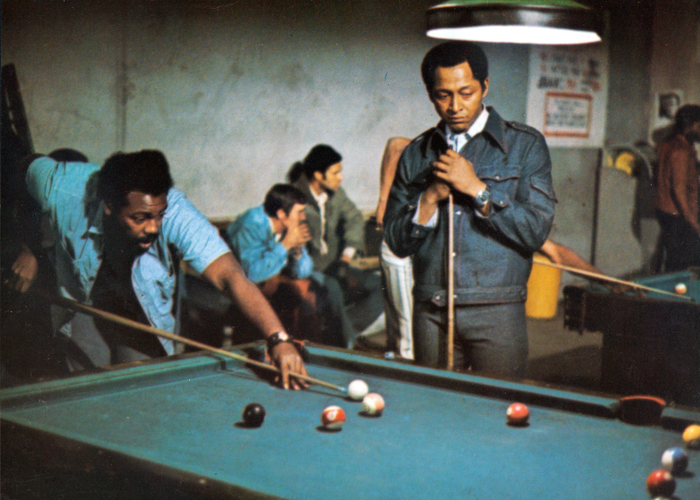

Hollywood seemed like the next logical step. “I knew it was going to be a flick up front,” Greenlee said of the novel in 1976. He teamed up with actor and director Ivan Dixon to adapt The Spook Who Sat by the Door for the screen. Unsuccessful in convincing anyone in the Hollywood establishment to help finance the film, Greenlee and Dixon went grassroots and found backers in the Black community, raising as much as $850,000, mainly from independent investors. The remainder of their $1 million budget came from United Artists, who agreed to distribute the film.

Greenlee served as coproducer and cowrote the screenplay. Dixon, known for his roles in 1964’s Nothing but a Man and the sitcom Hogan’s Heroes, directed. The filmmakers commissioned a funky synthesizer-heavy soundtrack from Herbie Hancock, who knew Greenlee personally from their South Side days. The film’s casting director was Pemon Rami, a collaborator of Greenlee’s in Chicago’s independent Black theater scene who later worked in the casting departments of other locally set films like Mahogany and The Blues Brothers.

The cast included actors with Hollywood résumés, including the Negro Ensemble Company’s Lawrence Cook as Freeman, along with local talent. Rami himself played Shorty Duncan, a young drug dealer whose killing by police sparks an uprising. Illinois Black Panther David Lemieux was working as a busboy at Hyde Park’s Chances R when he met Greenlee at the restaurant. He was later cast as Pretty Willie, a prominent member of the Cobras street gang that Freeman recruits for the revolution.

Refused permission to film in the city by Mayor Richard J. Daley, the crew shot most scenes in nearby Gary, Indiana, where Mayor Richard G. Hatcher offered the use of city resources, including the cooperation of the police department for the film’s climactic urban uprising scenes. The crew did capture some Chicago footage surreptitiously; viewers see Freeman and members of his guerrilla army at “L” stations along 63rd Street and, with poetic justice, Chicago’s City Hall during an explosion sequence.

The film had local flavor and was met with local fanfare. Its official premiere took place in Chicago at the Woods Theatre in the Loop, posting a successful $62,000 opening weekend there. A week and a half earlier, an audience in Greenlee’s Woodlawn neighborhood had a chance to see the film at a benefit opening at the Maryland Theatre on 63rd Street. “It was a full house,” casting director Rami recalls. “People were elated. We got standing ovations. It was the talk of the town.”

But the film also quickly stirred unease. The Defender ran an article praising the film as “Greenlee’s masterpiece” with a portentous headline: “Will ‘Spook’ Touch off Race Warfare?” Elsewhere the paper advised the viewer that “one must ‘keep his cool’” and take the film as entertainment only. Before long Greenlee and his collaborators began to notice theater exhibitors truncating their runs. The manager of the McVickers Theater in the Loop told Greenlee that FBI agents had visited him and encouraged him to pull the film. “They would sit the exhibitor down and gently tell him that this film was dangerous and could cause all kinds of difficulties,” Greenlee said. He also heard rumors that agents had pressured United Artists to stifle the film’s distribution. The Spook Who Sat by the Door had lived up to its name, in Greenlee’s view, spooking those in power in the government and the film industry. Soon the film all but vanished from public view.

For the next 30 years, it circulated underground. In addition to periodic screenings at art houses and campuses, The Spook Who Sat by the Door gained a larger following through unauthorized home videos that emerged in the 1980s. These bootlegs helped keep the film alive in the public consciousness—and on the radar of interested exhibitors who might show it publicly. Doc Films first screened The Spook Who Sat by the Door in the Winter Quarter of 1990 as part of its Black American Cinema series. Four years later, Doc presented the film again with Greenlee as a special guest.

While the film was percolating underground, Greenlee was too. After the original theatrical run ended in 1974, he made his career primarily on the college lecture circuit. The Spook Who Sat by the Door was a sensation among students and activists of the Black Power era, and campuses in the 1970s welcomed Greenlee. He published a second thriller, Baghdad Blues, with Bantam Books in 1976, drawing from his experiences with the USIA in Iraq during the 1958 revolution.

But around 1980, Greenlee remembered, a generational shift started to mean less student interest in the book and film’s militant themes. So he settled in a remote rural area of southern Spain for much of the ’80s and ’90s—“the perfect place to work,” he called it—returning to the United States for several years at a time. He churned out poems, novels, stage plays, screenplays, and an autobiography, most still unpublished and unproduced, and several stamped by the author’s musical propensities (like the novels “Djakarta Blues” and “Mykonos Blues,” which form a Foreign Service trilogy with Baghdad Blues).

Indeed, Greenlee’s book titles announce a central tenor of his work. “My man is a blues man,” Greenlee remembered his second wife, actress Yvette Hawkins, once saying. Throughout his body of work, Greenlee identified with the segment of society he called the Black urban masses. For Kenneth Warren, the Fairfax M. Cone Distinguished Service Professor in English, that sentiment places Greenlee in a major tradition of 20th-century writers, most famously Langston Hughes, who put the culture of ordinary folks at the center of Black literature.

But The Spook Who Sat by the Door may have an even deeper pedigree, Warren notes. The literature of Black rebellion extends back to Martin R. Delany’s Blake, or The Huts of America (1859, 1861–62), one of the earliest novels by an African American writer. It also includes such works as Sutton E. Griggs’s Imperium in Imperio (1899), about a revolutionary secret society striving to set up an independent Black republic in Texas, and George S. Schuyler’s Black Empire (1936–38), a more satirical take on the Black nationalist theme. Greenlee himself said the author with whom he felt the closest affinity was detective novelist Chester Himes. Himes’s unfinished novel Plan B, published posthumously in the United States in 1993, depicts an armed uprising in Harlem.

Greenlee’s novel rides high astride this tradition, and the secret of its staying power may actually be that its appeal cuts across class positions. For poet Angela Jackson, AM’95, who was a member with Greenlee of Chicago’s Organization of Black American Culture, the novel finds an audience from generation to generation because of the marginalized youth in whom it invests the possibility of social change. “I think the important thing that he’s saying is that young people, who people don’t think of as being valuable parts of our society, can be the ones who can transform our society,” Jackson says.

Meanwhile, Rami observes that the character of Dan Freeman has been a potent model for those in higher social positions. “Yes, it was about a revolutionary,” Rami says. “But more importantly, it was about Black men, specifically, who were in corporate America and had to be everything but themselves, in terms of shadowing what they really, truly felt and what they believed, and then going back and doing things within their own community.” In many corners of popular culture, The Spook Who Sat by the Door has become a byword for a certain stealthy subversive energy.

The film, too, has become a classic. A restoration and authorized home video release appeared in 2004. Less than a decade later, the movie joined the National Film Registry of the Library of Congress as one of the country’s “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant” films. Behind that achievement was possibly a different kind of stealthy act: Greenlee’s collaborator Ivan Dixon had given preservationists a chance to recover a film many seem to have wanted lost when he put the negative into storage under a false name, keeping it undercover.

There is plenty of other work by Greenlee left to be rediscovered, marked both by his local roots and his years abroad. The plays he wrote in Spain include Lisa Trotter, an adaptation of Lysistrata set in Chicago’s Robert Taylor Homes. The only play of Greenlee’s ever staged, South Side Blues, was done as a small community production. Meanwhile, The Spook Who Sat by the Door is bound to attract a new generation of fans through an upcoming television adaptation on FX.

Greenlee was a man who gave up studying international relations at UChicago for a life of international travels, but familiar places mattered to him, says Natiki Montano-Pressley, Greenlee’s daughter from a long relationship with actress and dancer Maxine McCrey. Even overseas, in the varied locales that inspired the far-flung settings of his works, Greenlee would return to places where he had found comfort, meaning, or a sentimental connection.

Chief among those places, Chicago remained his home port. Greenlee lived his final years back in Woodlawn, near 62nd Street and Kenwood Avenue, and kept local establishments like Daley’s Restaurant and Jimmy’s Woodlawn Tap on his rounds, according to Rami, Greenlee’s friend until the author’s death. Acting as his own distributor, Greenlee sold copies of his books out of his shoulder bag, along with autographed DVDs of his film. He had decided years ago how best to preserve his independence as an artist. As early as 1975, Greenlee saw a culture industry awash with people plying work “totally lacking in moral concept,” and he was not afraid to go it alone on principle: “I won’t have anything to do with amoral dudes.”