Credit cards. (Photography by Sean MacEntee, CC BY 2.0)

Chicago Booth assistant professor Abigail Sussman explores our preoccupation with saving money at all costs.

Imagine you need $1,000 to pay for an emergency expense. Do you tap your savings account or put the money on a credit card?

In terms of wealth building, it usually makes sense to draw from liquid assets before taking on debt. But many participants in a recent study coauthored by Chicago Booth assistant professor Abigail Sussman expressed willingness to put at least some of the money on high-interest plastic rather than withdraw the full amount from low-yield savings, especially if they were told the money in the account had been earmarked for something important.

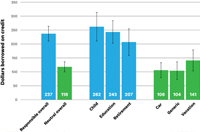

The graph shows the mean dollar amount the study’s participants said they would put on a credit card to help pay for the $1,000 expense, separated by the type of savings account they otherwise would have been drawing from. The average amount borrowed was higher among participants who were told their savings accounts were for “responsible” purposes—child-related expenses, education, or retirement—than among those who were told the savings were undesignated or were for a vacation or a new car. The study’s findings were published in the Journal of Marketing Research.

Sussman, who studies mental accounting techniques and personal finance strategies, says preserving savings makes people feel financially competent. So much so that when emergency expenses arise they’re often willing to incur the additional cost of credit card interest rather than see their savings account balance drop. Taking money from savings, especially when the money had been allotted for something else, makes people feel irresponsible, and that “causes them to engage in this costly borrowing behavior,” she says.

Personal finance management can be complicated, so many people tend to focus on one goal at a time, says Sussman. Often that’s to save as much as possible. “You open up the paper and see headlines about Americans failing to save,” she says, which can be a problem. Saving is important, but overemphasizing high account balances shortchanges other financial priorities, like building wealth, and neglects people “who don’t necessarily have the luxury of saving.”

Sussman advocates a big-picture approach to wealth management, treating assets and debt equally while taking into account personal circumstances and individual priorities. She recommends holistically identifying personal financial goals and then working to define subgoals to help reach them—including but not limited to saving.