Matthias Doepke, PhD’00, and coauthor Fabrizio Zilibotti’s book Love, Money, and Parenting: How Economics Explains the Way We Raise Our Kids (Princeton University Press, 2019) takes a global and historical perspective on how parenting has been transformed in an economically unequal world. (Illustration by George Peters/istock.com)

For some parents, life is a rat race they want their children to win. For others, it’s a race they’ve already lost. Why macroeconomics plays a role.

Families are private worlds, operating in ways that can be hard to understand from the outside (and, often, the inside). And yet, itʼs the sum of these many intimate, mysterious spheres that makes the world we know.

This was one of the lessons Matthias Doepke took from Gary Becker, AMʼ53, PhDʼ55, as a UChicago PhD student. Becker helped him see that “what families do really has important macroeconomic implications,” says Doepke, PhDʼ00, now a professor at Northwestern University. Todayʼs economy stems from many personal choices about when or if to marry, how many children to have, and where to raise them and send them to school. The influence runs the other way too: economic factors shape our individual choices about parenting.

Thatʼs the argument of Love, Money, and Parenting: How Economics Explains the Way We Raise Our Kids (Princeton University Press, 2019), coauthored by Doepke and Fabrizio Zilibotti of Yale University. The book takes a global and historical perspective on how parenting has been transformed in an economically unequal world, where the divides are stark—both between wealthy and less wealthy nations, and within wealthy nations.

A central theme in Love, Money, and Parenting is the rise of so-called helicopter parenting in industrialized countries. Parents hover for a reason, Doepke and Zilibotti contend: in countries including the United States, the United Kingdom, and China, a comfortable life is increasingly hard to attain without a top-notch education, and even with one. While the turbocharged mode of parenting that has emerged in response is mostly the province of the middle class and up, it affects everyone fighting for a piece of the shrinking pie. Higher-income parents are anxious and lower-income parents are shut out.

Doepke and Zilibotti interweave quantitative data with their own experiences as children and parents. As Europeans now based in the United States (Doepke is German, and Zilibotti, who is Italian, has lived in Sweden, the United Kingdom, and Switzerland), they have witnessed how child-rearing can differ over time and from place to place, a perspective that informs the book. Doepke considers himself a prime example of the changes he studies: despite loving his own low-key, unsupervised childhood, he has taken a far more hands-on approach to raising his three sons.

But he and Zilibotti see a common foundation underlying all parenting approaches, writing, “We believe that, broadly speaking, parents try their best to prepare their children for the society in which they will live.” In societies divided between haves and have-nots, using all the means they can to get ahead doesnʼt save some families from getting stranded.

“One thing thatʼs maybe both good and bad about economics ... is that we really like to generalize,” Doepke says, “because we have this view of people as being more or less all the same.”

When it comes to studying parenting, the economistʼs way of thinking has its pitfalls—clearly, there is no way to neatly classify the millions of daily interactions parents and children have, or to capture all the experiences that inform those interactions. But by generalizing, itʼs possible to compare times and places at scale, a practice of zooming out that “paints a clearer picture that is harder to see if you just focus on one particular time or place at a time,” Doepke argues.

To understand changes in parenting, Doepke and Zilibotti rely on the work of the late developmental psychologist Diana Baumrind, who in the 1960s developed an influential theory of parenting styles. These styles are defined by their levels of responsiveness (how communicative and attuned to their children they are) and demandingness (how much they monitor their children and set limits).

Authoritarian parents are characterized by high demandingness and low responsiveness (“eat your broccoli”), permissive parents by low demandingness and high responsiveness (“eat your broccoli if you want”), and authoritative parents by high demandingness and high responsiveness (“I want you to want to eat your broccoli”). Neglectful or uninvolved parents are neither responsive nor demanding. These styles differ in how much they ask of parents: Doepke and Zilibotti characterize authoritative and authoritarian parenting as more intensive, in that they require time, energy, and sustained focus.

Of course, parents arenʼt necessarily deliberate in their choices. “I donʼt think anybody, even economists, makes an Excel spreadsheet where they list the pros and cons of different parenting styles,” Doepke says. But, he argues, parents constantly if implicitly consider the future costs and benefits of their choices. Little Johnny may not want to study today, and you may not be in the mood to argue about it, but you believe heʼll suffer for not knowing his multiplication tables later. So, out come the flash cards.

Doepke uses his own case as an example: as a parent, he knows college admissions are important and competitive, and this ambient awareness makes him “a lot more anxious about academic outcomes than my own parents would have been.” As a result, heʼs become—without necessarily thinking about it—much more aware of and involved in his sonsʼ schoolwork than his parents were in his. An unconscious choice is still a choice.

There are many ways to mark the shift in parenting in the industrialized world over the past half century, from the rise in SAT prep classes to the advent of toddler yoga. But Doepke and Zilibotti argue that one particularly notable measure is time: according to data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, American parents in 2005 spent, on average, an hour and 45 minutes more per day with their children than they had in the late 1970s. Those precious moments are devoted to what youʼd expect: shared activities, like games and reading, and (no surprise) homework. Parents and children in Canada, parts of Europe, and the United Kingdom are also spending more structured time together.

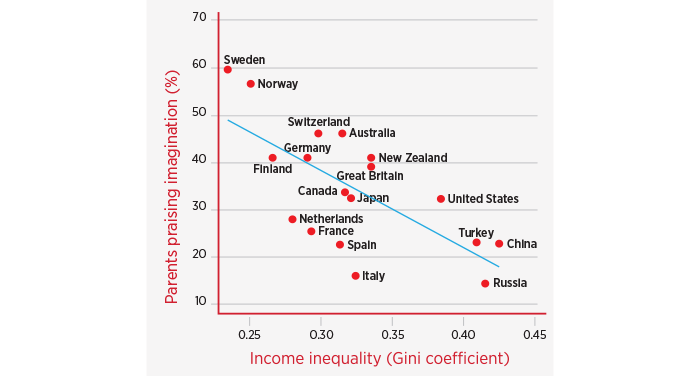

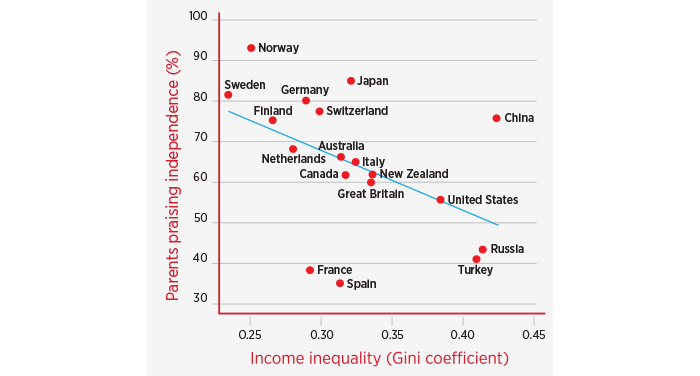

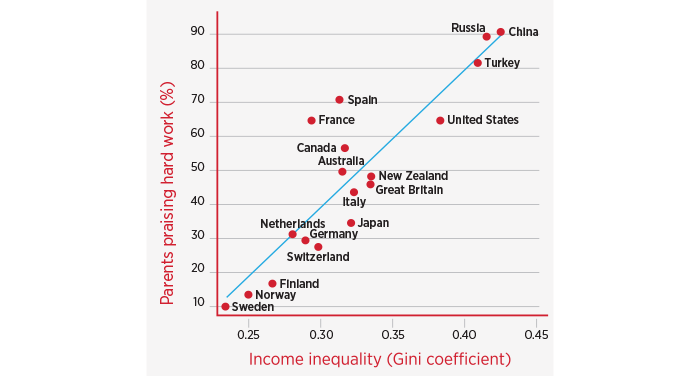

Another related measure is the percentage and distribution of parents choosing intensive (that is, authoritarian or authoritative) and nonintensive (permissive) parenting styles. To capture those trends, Doepke and Zilibotti turned to the World Values Survey (WVS), a questionnaire administered globally that includes questions about respondentsʼ child-rearing values. Parents can select up to five values from a menu that includes tolerance and respect for others, obedience, hard work, independence, imagination, and religious faith.

To Doepke and Zilibotti, certain values on the WVS typify Baumrindʼs parenting styles: authoritarian parents value obedience above all, while permissive parents gravitate toward imagination and independence, and authoritative parents hard work.

As they expected, they found enormous variation in parentsʼ top-five values across different countries. For example, some 90 percent of Chinese parents and 65 percent of American parents rated hard work among their most important values. In Nordic countries (Sweden, Norway, and Finland), only 11–17 percent of parents said the same. In these countries, independence was a top goal, with, for instance, 93 percent of Norwegian parents including it among their top-five values.

The figures certainly jibed with Zilibottiʼs experience living in Stockholm, where parents fretted that too much formal instruction might hinder their childʼs development and chose year-round outdoor preschool programs. After hearing about these forest nursery schools, Zilibotti notes, he and his wife nodded politely and enrolled their young daughter in a nursery school with four walls and a roof.

As parents and children began spending more time together, and intensive parenting became more widely practiced, something else changed too: income inequality began to rise across the industrialized world. One key measure of inequality, the ratio between the income share of the richest and poorest 10 percent of the population, increased by nearly 70 percent in the United Kingdom and 107 percent in the United States between 1974 and 2014. Even traditionally egalitarian countries, including Sweden and the Netherlands, saw modest increases.

While many factors explain the growth of inequality, one important dimension was a growing income gulf between more and less educated workers, Doepke and Zilibotti write. The economic fates of workers with high school diplomas, college degrees, and postgraduate degrees began to diverge more sharply in the 1980s. While in the 1970s, workers in the United States and United Kingdom with a postgraduate degree earned about the same as college graduates, by 2009, they earned an average of a third more. And not all college degrees are created equal: there is a pronounced income gap between workers with degrees in engineering and in the humanities. The financial stakes of education are high.

In fact, Doepke and Zilibotti contend, these three phenomena—the rise of intensive parenting, the growth of inequality, and the heightened value of higher education—are interconnected. As inequality rises and education begins to matter more for their children’s futures, parents have a strong incentive to become more involved in their childrenʼs everyday lives and schooling.

The results of the WVS provide one tidy illustration of their point: when they plotted income inequality against the percentage of parents who selected particular values, striking patterns emerged. Inequality had a strong positive correlation with the share of parents in a given country who valued hard work, and a strong negative correlation with the percentage of parents valuing imagination and independence. (See charts.)

They also found that, as economic inequality increases, the percentage of parents choosing more intensive parenting styles (as measured by the WVS) increases within countries. Even egalitarian Norway, where permissive parenting remains the norm, saw upticks in authoritarian and authoritative parenting styles from 1996 to 2007, a period when inequality also increased.

The time and energy authoritative and authoritarian parents devote to their children is at least well spent when it comes to educational outcomes, according to the Program for International Student Assessment, or PISA, a standardized test issued every three years to more than 500,000 students around the globe. The test includes questions about parent-child interaction that Doepke and Zilibotti used to extrapolate whether children had intensive or permissive parents.

Then, to avoid directly comparing countries with very different school systems, they compared within-country results of the PISA among children of intensive and nonintensive parents—that is, they compared the scores of South Korean children of intensive parents and nonintensive parents, and French children of intensive and nonintensive parents, while controlling for parentsʼ levels of education.

Parental education matters, they found, but parenting style matters more. In South Korea, having two highly educated parents added an average of only seven points to a childʼs math score on the PISA. Having parents who practiced an intensive parenting style added an average of more than 20 points, regardless of those parentsʼ levels of education. The same pattern held true in nine of the 11 countries that took the PISA in 2012.

So, despite the cultural hand-wringing about overparenting, itʼs hard to argue it hasnʼt yielded its intended effects; greater involvement does translate to better educational outcomes. In that sense, Doepke and Zilibotti say, helicopter parenting “can be understood as a rational response ... to a changed economic environment.”

But where does this leave parents who canʼt—either logistically or financially—devote hours to helping their children with schoolwork or shuttling them between enriching after-school activities?

Nowhere good, especially in high-inequality countries, Doepke and Zilibotti conclude. Time is a resource that low-income families, where parents often work multiple jobs with unpredictable schedules, do not have in abundant supply. And, unlike the busy but wealthy, they can seldom buy the attention of caregivers who will intensively parent in their absence.

Lower-income children with intensive parents do better, educationally and economically, than lower-income children without them—but they still face a much steeper climb into long-term financial stability. The hurdles are enormous: less safe neighborhoods, unstable housing, schools and teachers with fewer resources, and more.

To Doepke and Zilibotti this parenting gap risks becoming a parenting trap. If an unattainably intensive parenting style is necessary for a child to succeed academically, and academic success is the only path to stability or social mobility, then there is no way forward.

Itʼs worth asking whether any parent, whatever their income, should have to worry quite so much or try quite so hard. Doepke, understatedly, describes the conditions in the United States as “not very favorable” for having children—parental leave is not guaranteed, childcare is expensive, and intensive parenting takes a toll. Doepke himself remembers finding aspects of American helicopter parenting, especially the heightened early focus on higher education, “bizarre—you know, to think about what instruments a six-year-old might play and ... what that could mean for getting into college.” Parents and children feel the pressure.

As economists, he and Zilibotti are not entirely sold on policies with the sole aim of reducing inequality. In a capitalist society, they believe, some degree of inequality is inevitable and even desirable. But they also see the danger of letting things continue as they are, with everyone overwhelmed and lower-income families at much higher risk of getting left behind.

Partly through personal experience, Doepke and Zilibotti find merit in Scandinavian-style family-friendly policies, especially those focused on the early years, such as parental leave, public preschool, and affordable childcare options. These can help put all children on equal footing and ease the burden on parents.

Citing research by James J. Heckman, the Henry Schultz Distinguished Service Professor in Economics, Doepke argues that “investing in early childhood education ... is by far the highest return and the most urgent priority.” Itʼs the time when children are developing most dramatically and when parents need the most help.

Today, parents are more in need of help than ever. During the COVID-19 pandemic, mothers in particular have faced herculean challenges. In November, Doepke coauthored a paper showing that women are suffering the harshest effects of the current recession—both because they disproportionately work in the most affected sectors, such as hospitality, and because in many families they are still the default caregivers when other childcare options are ruled out.

Once again, his own household is illustrative: as an academic, Doepke was able to work from home. His wife, a casting director for film and television, saw her industry shut down almost completely. Early in the pandemic, their normally balanced responsibilities shifted and she did more of the childcare—“not an easy adjustment,” he reflects.

For all its damage, the pandemic may give rise to more family-friendly workplace policies, at least in some sectors, now that many organizations have learned the viability of remote work. A longer-term shift toward flexible work hours and locations will help mothers and fathers alike, Doepke says. “This is really great news for families. ... I think itʼs going to also make combining families with careers easier—and therefore, also easier to have children.” What kind of world those children will live in is up to us.