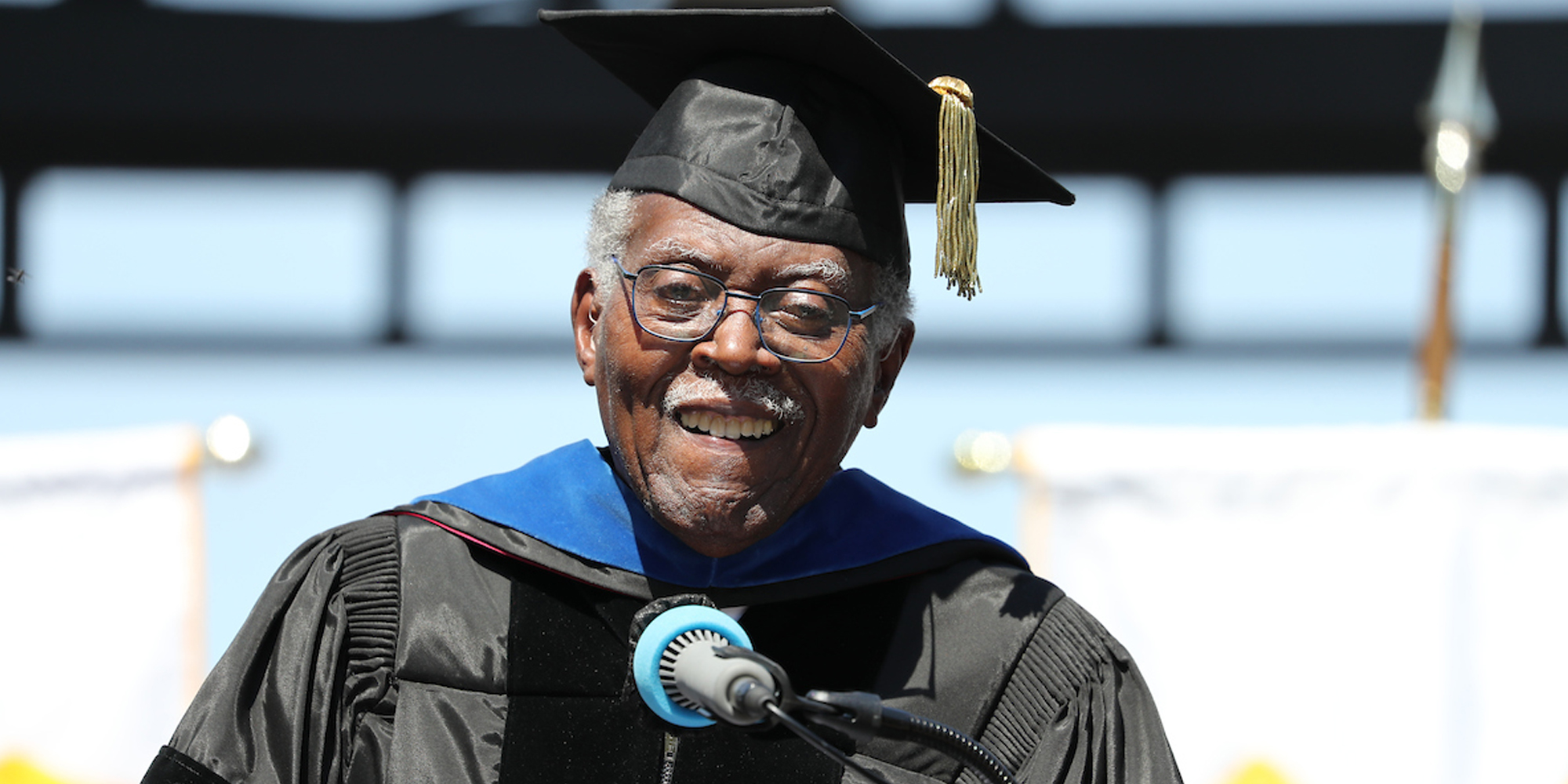

Jackson State president emeritus John A. Peoples Jr., AM’51, PhD’61, speaking at a long-delayed commencement ceremony for the Class of 1970 this past May. (Photography by Charles A. Smith)

John A. Peoples Jr., AM’51, PhD’61, helped Jackson State endure and thrive after tragedy.

As an aspiring math teacher just out of college, John A. Peoples Jr., AM’51, PhD’61, thought of himself as pretty smart. While that self-appraisal would prove to be accurate, the University of Chicago subjected his hypothesis to rigorous scrutiny.

As an undergraduate at what is now Jackson State University—at the time, a teacher’s college for Black students—Peoples had been “Mr. Everything,” earning straight As, twice serving as student body president, and excelling in football and track. When he headed to UChicago to pursue a master’s degree in education, not everyone thought it was a good idea.

“Man, don’t go there, you’ll never get out,” the 95-year-old Peoples says today with a laugh, paraphrasing the chorus of discouragement he heard.

There were moments when he believed it himself. He recalls asking an instructor with a German accent to repeat something, only to have his intelligence—and that of everyone from Mississippi—impugned.

Thankfully, in the midst of his struggles, Peoples fell in with a circle of friends from Manley House who “kind of adopted me,” he says. “I was the only Black in that dormitory at that time, and they helped me to get through my degree.”

Born in Starkville, Mississippi, in 1926, Peoples had persevered through difficulty before without such support, drawing on a strength of character that would come to define his professional life. He was drafted into the US Marine Corps after high school and trained at the Montford Point Camp in North Carolina, where segregation was so stringently enforced that Black recruits could not so much as enter the main base at Camp Lejeune without a White escort. As president of Jackson State, he would steer the school through tragedy and expand its academic mission beyond training teachers, setting it on a path to become the nation’s 10th-largest historically Black college or university.

Peoples’s career in education began in Gary, Indiana, where he became Froebel High School’s first Black teacher in 1951. Continually passed over for administrative promotions, he was finally hired as an assistant principal at Lincoln Elementary School in 1958, then as principal at Banneker Elementary School in 1962.

In his 1995 memoir, To Survive and Thrive: The Quest for a True University (Town Square Books), Peoples writes that a friend had warned he would go further in his career if he kept quiet and deferred to White colleagues. That was not in his nature, and he believed his outspoken character undermined him in the eyes of his superintendent.

Still, Peoples gained admirers, resulting in multiple job offers—including one to become vice president at Jackson State and heir apparent to its longtime leader. Peoples decided to return to Mississippi, though he knew it would be difficult and even dangerous. In 1967 he assumed the presidency of Jackson State.

He arrived at a volatile moment. During his first three years as president, Peoples came to expect demonstrations over civil rights and the Vietnam War that escalated into clashes with Jackson police or residents.

Lynch Street, a busy road in Jackson, ran through the campus like a fuse, often becoming a flashpoint for conflict between the Black student body and passing White motorists. (Despite the name’s ominous resonance, the street commemorated John R. Lynch, a Black US representative during Reconstruction.) Drivers hurled epithets and objects; students responded in kind.

Peoples had to navigate delicate terrain: defending student expression on social issues but appealing to them for calm in the face of racist taunting, all while lobbying for academic resources from a recalcitrant state college board. “I wanted my revolution to take place through the production of progressive, freedom-minded teachers, lawyers, doctors, and entrepreneurs,” he writes.

By the spring of 1970, if he had not yet revolutionized Jackson State, Peoples had taken strides toward realizing his vision, doubling enrollment and recruiting talented students and faculty. As commencement approached for the Class of 1970, the disturbances of the previous three years had not resurfaced.

The peaceful spring would soon be shattered. On May 4, four Kent State University students were killed by the Ohio National Guard. Three days later, Jackson State students gathered to speak out against the killings and the US invasion of Cambodia that had prompted the Kent State protests. To Peoples, the rally seemed mild.

But on the evening of May 13, conflict flared between students and motorists, prompting the closure of Lynch Street. Against Peoples’s urging, local authorities allowed traffic through the next day; another round of rock-throwing erupted that night. When the street was barricaded again, calm returned.

Then a group of non-students set fire to a nearby dump truck. Firefighters arrived with 26 city officers, 40 state highway patrolmen, and an armored tank. National Guard troops also had been summoned.

The fire was soon doused, but the officers moved farther along Lynch Street into the heart of campus. About 200 students were outside Alexander Hall, a women’s dormitory, whose residents had already retired because of the evening curfew. According to James “Lap” Baker, a Jackson State senior at the time, Peoples had told them earlier in the evening to keep calm. “And that’s what [we] did,” Baker says, “because we listened to him.”

To the authorities, the crowd of students represented a threat. Orders to disperse, bellowed through a bullhorn, were met with defiance. Then someone threw a bottle into the street.

“When it burst,” Baker says, “all hell broke loose.”

Officers sprayed gunfire across both sides of Lynch Street, more than 400 rounds in a barrage that lasted 28 seconds. Bullets shattered glass and pocked the walls of Alexander Hall, where authorities later claimed to have seen a sniper, though there was no evidence of such a threat.

Phillip Lafayette Gibbs, 21, and James Earl Green, 17, were killed. A dozen others were wounded. Gibbs, a junior studying political science, was married with a young son and another child on the way. Green, a high school senior, was walking home from his job at the neighborhood store Wag-A-Bag.

From his home about a block away, Peoples thought the sound might be fireworks. When he learned of the shooting, Peoples opened his door to discover two National Guardsmen stationed there to protect his family. They were under orders not to let him leave.

Peoples felt helpless. He heard screams and sirens, then the sounds of a crowd advancing toward his house. The students wanted him to see the scene for himself, and the guardsmen at the door did not stop Peoples this time.

“And sure enough, when I got there, it was really something awful to see,” he says. “You could smell the gunpowder.”

Peoples climbed on a table to address the students , but he had no words.

“Dr. Peoples, why don’t you pray?” came a voice from the crowd. And so he did, sensing a calm come over the crowd that ended as soon as he said “Amen” and told them to return to their dorms.

Under no circumstances would they budge, a response Peoples couldn’t help but respect. Shattered glass and bullet holes in the walls were a powerful argument that they would be no safer inside. He stayed outside with them, singing hymns and freedom songs. Peoples canceled the final days of the term, along with the commencement ceremony.

Though they occurred just 10 days after the Kent State tragedy, the Jackson State killings did not attract the same national attention or outrage. No one was ever punished for the deaths of Gibbs and Green. On campus, the reaction moved from anger to resignation.

The tragedy changed Peoples; near the one-year anniversary of the killings, a student activist remarked that the president had “aged 10 years in 12 months.” He channeled his grief into his work, continuing his dogged efforts to expand Jackson State and achieving a major goal—university status—in 1974. Peoples stepped down in 1984, having transformed an undergraduate teacher training school into a multifaceted institution offering doctoral degrees in numerous disciplines.

“It just shows the tremendous vision and drive and dedication that Dr. Peoples had then, and still has,” Baker says. “He was strong. He was strong.”

There was work left undone, however, until 2021. In May, Peoples spoke during a commencement ceremony for the Class of 1970, held on the Gibbs-Green Memorial Plaza that long ago replaced the volatile stretch of John R. Lynch Street. The site of bloodshed and symbol of the barriers to building Jackson State is now a pedestrian path for students attending the university that Peoples envisioned for them.

Jason Kelly is associate editor of Notre Dame Magazine.