(©2018 Robert Neubecker c/o theispot)

A UChicago professor spearheads an initiative to end mass incarceration.

Most people believe in a world of second chances,” said Senator Dick Durbin (D-IL) at the Smart Decarceration Initiative conference held on the UChicago campus in November 2017. Durbin’s voice is just one in an emerging chorus of public officials, researchers, and community activists seeking alternatives to a system of mass incarceration that has taken hold in the United States like nowhere else in the world. “Now it’s up to us,” Durbin said.

The scale of the problem is difficult to overstate. In a now familiar story, the United States has emerged as the global leader in incarceration, driven by efforts such as the federal Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994, mandatory minimum sentences (including a host of state-level “three-strikes” laws), and a decades-long war on drugs. Today the United States has under 5 percent of the world’s population but over 20 percent of its prisoners. Its total prison and jail census exceeds that of any other country, including the closest runners-up, China and Russia.

But the high-water mark for incarceration in the United States may be behind us. In 2009, after 37 consecutive years of growth, the US incarceration rate finally leveled off and began to decline slightly. This shift may have been a response to short-term budget crunches in the Great Recession, but it has given lawmakers an opportunity to question what is still an over $50 billion annual expenditure on incarceration—difficult to justify in the face of research showing that time behind bars generally increases rather than decreases chances of recidivism.

And no budget line captures the human costs of incarceration: permanently disrupted families, educations, housing, and careers, all borne disproportionately by people with mental illness and communities of color, further entrenching existing inequities.

Remarkably, the intentional reduction of incarceration, or decarceration, now has potentially as much bipartisan appeal as “tough on crime” legislation once did, winning advocates from Black Lives Matter activists to former Republican House Speaker Newt Gingrich. The question is what to do with this historic opening.

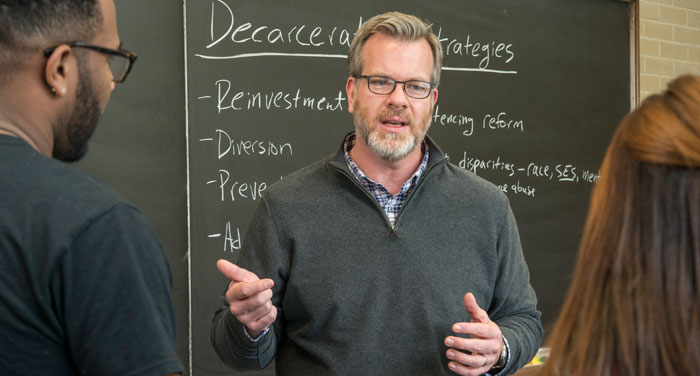

Matthew Epperson, an associate professor in the School of Social Service Administration, has more than an academic understanding of the effects of incarceration. With 15 years of experience as a practicing social worker, including six as a crisis mental health counselor at a county jail in Grand Rapids, Michigan, he has seen firsthand how the criminal justice system fails to meet the needs of individuals and communities.

For a significant proportion of the inmates Epperson worked with, jail was part of a recurring pattern generated by untreated mental illness or addiction. “There were some folks I knew on a first-name basis because they were in and out of the jail, sometimes weekly, sometimes multiple times in the same day.” For them, jail was neither a deterrent to future behavior nor a treatment for current problems. To Epperson, it felt like a waste. So he set up a program to divert individuals with serious mental illness away from jail and into treatment. Incarceration and mental illness remains a focus of his research at SSA today.

When Epperson began as a social worker in the mid-1990s, the term “mass incarceration” was not on the tip of everyone’s tongue. We did not have Michelle Alexander’s book The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness (The New Press, 2010) or the documentary film 13th (2016), each of which traces disparities in the criminal justice system to a troubled historical legacy rooted in slavery. Nor did we have the TV series Orange Is the New Black (2013–), with its humanizing portrayal of prisoners. Even a sympathetic insider might have been unaware of the full scope of the problem.

A light-bulb moment for Epperson came at a conference after his first year at the jail, which outlined how the United States had become historically and globally unique in its reliance on incarceration. “It wasn’t just happening in Grand Rapids, Michigan. It wasn’t just happening to the person across from me. It was happening everywhere.”

Epperson has also seen mental health services from an administrative perspective, leaving Michigan for a stint as a mental health administrator in North Carolina. There he felt unprepared by his experience as a clinician for such tasks as overseeing the center’s managed care and mental health service contracts. He says that his lack of research knowledge was typical of mental health administrators.

Sensing how much more there was to learn, Epperson decided to get a PhD—“probably the best career decision I made,” he says. As a professor he could still work directly with the community while also conducting research and teaching a new generation of students to critically evaluate the criminal justice system.

At SSA Epperson’s research focuses on risk factors for criminal involvement among individuals with mental illness, as well as the development of conceptual frameworks for effective and sustainable decarceration. He cofounded the Smart Decarceration Initiative in 2014 with collaborators at the Brown School of Social Work at Washington University in St. Louis. However, plans are underway for Epperson’s work in this area—now called simply “Smart Decarceration”—to be housed within a new criminal justice–focused center to be established at SSA. Epperson is also a leader of the Promote Smart Decarceration initiative of the American Academy of Social Work and Social Welfare, one of that organization’s 12 Grand Challenges for Social Work intended to address the nation’s toughest social problems.

The goal of Smart Decarceration is to transform the criminal justice system by reducing the incarcerated population in a way that redresses social disparities and enhances public safety. Its strategy—demonstrated so far by a book and two national conferences—is to source perspectives and evidence from everyone researching, working in, or impacted by the criminal justice system.

“Incarceration could look quite different in 10 or 20 years,” Epperson says. “We want to shape how it looks different.”

For Epperson, it’s critical that we scrutinize the function of incarceration. Despite the optimistic 18th-century conception of the penitentiary as a place for penitence, or the righting of one’s character through self-reflection, prisons and jails are actively hostile places for rehabilitation. Nor do harsh sentences seem to deter criminal behavior in the general population. Incarceration may inflict retribution, but this is an unquantifiable and, to Epperson’s mind, dubious goal. In the end, Epperson thinks that incarceration is only effective at incapacitating individuals who pose an imminent threat to the community—perhaps just a small fraction of those languishing in America’s jails and prisons today.

Narrowing the role of incarceration in society requires outlining alternatives. A host of other criminal justice sanctions are available: jail-diversion programs provide community-based treatment to those with serious mental illness or substance abuse disorders; deferred prosecution allows charges to be dropped in exchange for making restitution to victims or completing rehabilitation programs; and community supervision (probation and parole) allows individuals to maintain family and work lives while serving a sentence. Some jurisdictions use these interventions regularly within specialized courts that seek to address the needs of particular communities: drug courts, mental health courts, and veterans courts.

Epperson is currently coleading a study on deferred prosecution programs in Cook County, Milwaukee County, and St. Louis, with the aim of designing a future randomized trial experiment on the practice. In his view, calling such approaches “alternatives” already cedes too much ground, since it implicitly accepts that incarceration is the default remedy. To his mind, incarceration is just one tool in the tool kit—the heaviest and bluntest one. “How did we end up in a place where if somebody has a drug habit and they steal something from a store … our default response would be they should sit behind bars tonight and possibly for the next few months or years?”

Borrowing from the field of medicine, Epperson suggests that different cases require different levels of care. Incarceration may be viewed as a particularly high level of care for protecting public safety. You don’t perform surgery on a scraped knee, increasing expense and risk for no reason. And time behind bars may be an inappropriate remedy for a drug offense. Whether in medicine or criminal justice, inpatient care is to be avoided where outpatient care will do.

A medical lens on the issue also tends to make discussions more scientific and less narrowly moralistic. “In adopting a public health approach,” writes Ernest Drucker, a New York University professor of global public health, “decarceration efforts are less likely to blame and stigmatize individuals; instead, decarceration can focus on the adverse policies and pathogenic environments imposed on entire populations.” A participant in the Smart Decarceration Initiative’s 2015 inaugural confernce, Drucker has recently edited an anthology titled Decarcerating America: From Mass Punishment to Public Health (The New Press, 2018).

A public health approach may require changes throughout the criminal justice system. For instance, Cook County sheriff Tom Dart opened a new Supportive Release Center in 2017 with grant funding from UChicago Urban Labs and in partnership with Treatment Alternatives for Safe Communities and Heartland Alliance Health. After they’re released, some of the most in-need former inmates can now spend the night at a repurposed mobile home near the jail, where they may eat, sleep, wash clothes, and arrange for services such as housing assistance and mental health counseling. Dart sees it as obvious that this model should be scaled up and replicated widely.

Effective decarceration would depend largely on the actions of prosecutors, Epperson says. This means that prosecutors should not be rewarded for processing large volumes of cases with high conviction rates, but for carefully applying sanctions that don’t unduly disrupt the lives of individuals or communities. “A prosecutor’s role is really to promote safety and justice,” he says. In that role, they “have to respond to the evidence that shows that just locking people up doesn’t achieve those things.”

Some prosecutors across the country are getting on board. For instance, Philadelphia district attorney Larry Krasner, a former civil rights lawyer, made headlines with the controversial idea that prosecutors ought to discuss the price tag of incarceration with judges during sentencing. Funds saved by using less expensive sanctions—say, court-mandated addiction treatment—could be used to address unmet needs in the community, potentially making everyone safer. John Chisholm, district attorney of Milwaukee County, Wisconsin, coauthored a chapter in the Smart Decarceration Initiative’s book, Smart Decarceration: Achieving Criminal Justice Transformation in the 21st Century (Oxford University Press, 2017), outlining principles for fair sentencing that address the seriousness of a crime while preserving the defendant’s basic means of citizenship.

An emerging leader in prosecutorial reform is Kim Foxx, the state’s attorney for Cook County, Illinois. Foxx was elected in 2016 as the first African American woman to lead the county’s prosecutor’s office, which is the second largest in the United States. Foxx has recommended the increased use of personal recognizance bonds, which allow low-risk defendants to sign a written promise to appear in court without the need for cash bail. As Katie Hill, director of policy, research, and development in Foxx’s office, described at the 2017 Smart Decarceration conference, attorneys are now encouraged to seek cash bail only as a last resort.

Many poor defendants nationwide sit in jail only because they are unable to afford bail. A September 2017 order by Cook County chief judge Timothy Evans required judges to set affordable cash bail for defendants not deemed to be dangerous. By December of that year, the population of Cook County Jail had reduced by 20 percent, dipping below 6,000 for the first time in decades.

Some contend that Cook County’s criminal justice reform has not gone far enough. The electronic monitoring systems that are commonly replacing bail can limit movement in a way that’s similar to incarceration. There are also concerns about judges’ uneven adherence to new policies. On the other hand, Sheriff Dart claimed in February 2018 that the new rules go too far, letting potentially dangerous suspects walk the streets. He delayed some releases for a short time while conducting additional case reviews—a move that prompted backlash from both activists and fellow officials. Even those seeking a change of course are learning to steer the ship together as it moves.

Mass incarceration was a decidedly bipartisan creation, driven by a Republican-led war on drugs, a 1994 crime bill authored by Democratic senator Joe Biden and signed by President Bill Clinton, and a flurry of three-strikes laws that were nowhere more punitive than in heavily Democratic California. Today mass incarceration is once again an area of emerging bipartisan agreement, but in the opposite direction.

One Democrat seeking to make amends is Senator Durbin. Speaking at the 2017 Smart Decarceration conference, he publicly regretted the criminalizing attitude adopted by the public and policy makers during the crack-cocaine epidemic of the 1980s. He also frankly indicated why he believes many Americans are readier for a more rehabilitative approach today: the opioid crisis is perceived as white and rural, whereas crack was understood as African American and urban.

Even with two forms of the same drug, racial and socioeconomic disparities are in plain view. The Fair Sentencing Act of 2010, authored by Durbin and signed by President Barack Obama, established an 18:1 sentencing disparity between crack cocaine and the powder form of the drug more popular among white and affluent users. The reason this law is considered a progressive reform is because it revises the ratio of 100:1 established under the Reagan administration in 1986.

The Smart Decarceration conference also featured a leading conservative voice on criminal justice: Marc Levin, the vice president of criminal justice policy at the Texas Public Policy Foundation’s Right on Crime initiative. Epperson draws on Levin’s perspective to supplement traditionally liberal or leftist arguments against mass incarceration with conservative ones.

Levin argues that we should employ the least restrictive criminal justice sanctions that are consistent with justice, while creating incentives rather than barriers to education and work. For the Right on Crime initiative, decarceration goes hand-in-hand with a conservative vision of “constitutionally limited government, transparency, individual liberty, personal responsibility, free enterprise, and the centrality of the family and community.”

For instance, of about 11.5 million Americans cycling in and out of jails each year, the majority are not convicted of a charge for which they are being held but are unable to afford cash bail, a system that arguably criminalizes poverty and vitiates the ideal of presumed innocence. Moreover, Levin points out, one-fifth of those in jail in many jurisdictions are there for unpaid fines for infractions that would not otherwise carry a jail sentence. “People end up in what basically is a debtors’ prison,” he says. One alternative, he suggests, is that courts be given the authority to assess the day fines—penalties limited to what an individual earns in a day—used in some European and Latin American countries.

Levin invokes a further principle, one that resonates with American religious conservatism: redemption. Incarceration and the restrictions on housing, educational opportunities, and job prospects that come with a criminal charge hinder individuals’ ability to pull themselves up, often when they are at their lowest point. It does not seem to be a system designed to offer second chances. One example of the antirehabilitative bent of the criminal justice system in recent decades is the banning of federal Pell Grants for prisoners in the 1994 federal crime bill. Educational grants for prisoners were partially revived under President Obama but face an uncertain future.

None of this is to mention cost savings, which are clearly appealing to fiscal conservatives. Why continue a $50 billion annual expenditure that at best yields highly mixed results and at worst is a massive waste of human and economic potential? Levin says that he leads with the fiscal argument: “The appetizer is saving money, and the main course is public safety, keeping families together, getting people in the workforce.”

Durbin echoed this sentiment at the 2017 Smart Decarceration conference: “We’re talking about the primary breadwinners in many families spending their peak earning years behind bars, instead of contributing to their families and society. They end up costing society as prisoners.”

Levin’s position is not a fringe view on the right. In fact, many are eager to brand prison reform as a conservative-led cause. Signatories to the Right on Crime initiative include the likes of Jeb Bush, Mike Huckabee, Rick Perry, and Newt Gingrich. Gingrich and conservative activist Pat Nolan went on record promoting Right on Crime in a 2011 Washington Post opinion piece, where they argued that a reduction in incarceration is a win-win that saves money while increasing public safety. “If our prison policies are failing half of the time, and we know that there are more humane, effective alternatives, it is time to fundamentally rethink how we treat and rehabilitate our prisoners,” they contended.

“Everyone running on the Republican ticket for the 2016 election except for one candidate was pretty vocal about the need for criminal justice reform,” Epperson says. “That had never been the case in a presidential election in the last 30 years.”

Opposition to mass incarceration has not entirely won the day among Republicans, however, as the GOP nomination, and ultimately the presidency, went to the sole tough-on-crime voice in the group.

This is not the first time the United States has looked to significantly downsize a major social institution. Epperson cites the lessons of the 20th-century deinstitutionalization movement in mental health care, in which long-stay state psychiatric hospitals—criticized as isolated and stigmatizing—were largely replaced by community-based care. (See “Learning from Deinstitutionalization” below.)

Epperson says that deinstitutionalization was successful in meeting its target of closing down facilities, which it did ahead of schedule. “But it wasn’t successful because lots of these folks ended up not getting adequate support.” The analogy is clear enough: deinstitutionalization, whether in mental health or the criminal justice system, requires an adequately funded successor system. The evacuation of the institution is not itself the goal.

But it’s more than an analogy. Prisons and jails are not just like psychiatric institutions. They are in fact the largest psychiatric institutions in the United States, containing 10 times the number of individuals with serious mental illness—conditions such as bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and major depression—as America’s remaining psychiatric hospitals, according to the Treatment Advocacy Center. Cook County Jail by itself holds more individuals with serious mental illness than any state psychiatric hospital in the United States.

Most inmates do not receive any treatment for these disorders while behind bars, and sometimes receive worse than no treatment. In 2015 the State of Illinois settled a class-action lawsuit brought by 11,000 state prison inmates claiming cruel and unusual punishment for alleged abuses including the withholding of medications, the stripping and humiliation of suicidal prisoners, and the use of extensive solitary confinement as punishment for symptoms. The settlement calls for new residential treatment facilities, hundreds of new staff to provide treatment, and closer monitoring and additional out-of-cell time for mentally ill prisoners in solitary confinement. (In October 2017 three legal organizations filed a motion against the Illinois Department of Corrections, claiming it hadn’t met its obligations under the terms of the settlement.)

Some officials are taking more proactive measures. As the New York Times has reported, Sheriff Dart took the unusual step in 2015 of appointing a clinical psychologist, Nneka Jones Tapia, as warden of the county jail. Even before becoming warden, Jones Tapia had overseen the offering of new services in the jail: collecting mental health histories, arranging for diagnoses and medication, and forwarding pertinent mental health information to judges so that they could consider it in their rulings. In March 2018 she stepped down as warden after three years on the job, saying she hopes to be a resource to the jail in the future as a collaborator.

As a fellow at the University of Chicago Institute of Politics in spring 2018, Jones Tapia led a series of seminars on the role of trauma in the criminal justice system—another important area of mental health crisis among the incarcerated.

Studies indicate that over 90 percent of inmates have high lifetime rates of traumatic experiences such as abuse, neglect, and witnessing violence. Symptoms commonly include anxiety brought on by associations with a traumatic event, which can lead sufferers to turn to drugs or alcohol for relief. Incarceration amplifies these effects, as incarceration is itself a traumatic experience. The problem is intergenerational: children of incarcerated parents are six times likelier than average to be incarcerated themselves.

Not everyone agrees that mass incarceration is a problem. Tough-on-crime rhetoric such as President Donald J. Trump’s resonates with the belief that a bad deed deserves punishment, while stoking the fear that either we or our loved ones may fall prey to malevolent forces in a dangerous world. At its most unseemly, such rhetoric appeals to dehumanizing, frequently racialized images of exactly whom decent people must be defended from. A concern for the welfare of perpetrators appears misplaced, the very definition of a mawkish bleeding heart.

Epperson says he recently got an email from a stranger in South Carolina that described a repeat offender who committed a violent crime while out on parole. To this correspondent, the case discredited Epperson’s entire approach. “So if you want to not incarcerate people I’d gladly put this person on a bus and send them to Chicago so you can deal with them.”

This touches on a concern of Epperson’s: that a high-profile case of recidivism could be used to justify a return to tough-on-crime policies. “There’s also hundreds of thousands of stories of people who are locked up and whose lives are made worse and are basically victimized by the system,” he says. “And so both of those stories need to be considered here.”

Violent crime in particular elicits a strong response, making it something of a taboo topic among politicians advocating for criminal justice reform. The safest way to critique the system is to conjure a sympathetic image of a nonviolent offender—perhaps one of the one-in-five incarcerated individuals in the United States serving time for a nonviolent drug offense. However, a case can be made that decarceration should include reduced sentences for violent crime as well. Todd Clear, a professor of criminal justice at Rutgers University who visited SSA in spring 2018, takes this position, arguing that the term “violent” names a misleadingly broad range of cases and that moderate sentence reductions for violent offenders are not linked to increased recidivism or significant public safety risks.

Other criticisms come from another direction entirely. Prison abolitionists, such as prominent social activist and scholar Angela Davis, argue that prisons are fundamentally illegitimate institutions that should be rejected outright rather than reformed. The abolitionist critique, says Epperson, is that reformers are only “tinkering around the edges” of the system. If abolition, not reformism, was the correct response to slavery, then perhaps it is the correct response to another form of institutionalized unfreedom that entrenches racial inequality in the United States.

Epperson acknowledges the abolitionists’ concern that we might settle for too little. How much incarceration is the right amount? Will minor successes lead to complacency? Nevertheless, he says, “I’m a pragmatist at heart.”

Epperson ultimately sees himself as a mediator among different forces for change in the criminal justice system. This includes his teaching as well as his work with Smart Decarceration. For instance, he teaches a course on decarceration in which he has students debate different perspectives on the issue such as abolitionism or Right on Crime. “The students are developing their own policy ideas and interventions, which is really exciting because even if a handful of them go on to do those things there’s a much greater impact.”

Decarceration, of course, is not a matter of closing down some facilities, pocketing the savings, and calling it a day. Epperson cites the idea of “justice reinvestment.” Although this term traditionally refers to the diversion of funds from prisons and jails to other parts of the criminal justice system, he says, the concept is being broadened to include addressing the upstream social and economic conditions that lead to involvement in the criminal justice system in the first place.

“Are we making the right investment? Are we making the right impacts?” asks Esther Franco-Payne, AM’99, who spoke at the 2017 conference. Justice reinvestment concerns Franco-Payne in her work as executive director of Cabrini Green Legal Aid, a Chicago nonprofit that provides holistic services to individuals affected by the criminal justice system. “You see multiple generations of people in the same family impacted by incarceration,” she says. “We need to really think about what is it that we need to do to break that cycle as we continue to spend billions and billions of dollars on this nationally.”

Mental health services and substance abuse treatment are clear targets for justice reinvestment. So are public education and economic opportunities for low-income neighborhoods and communities of color. And yet no complete list of approaches can be offered in advance, nor are academic outsiders necessarily in the best place to prescribe what communities need. Part of Epperson’s philosophy is to be flexible and listen.

To that end, the University of Chicago Women’s Board awarded Epperson a 2018–19 grant for a project to assess the strengths and needs of the high-incarceration Chicago neighborhoods of Austin and Washington Park. Epperson’s team is creating a community advisory board consisting of ordinary residents, officials, and formerly incarcerated individuals, allowing communities to define their own problems while using evidence to examine how to address them. Movements for civil rights, women’s rights, or gay rights would have been dead in the water if they had not been led by the people most affected, Epperson says, and there’s no reason to think that a movement for the formerly incarcerated and their communities should be different.

Learning from deinstitutionalization

The late 20th-century shift in mental health care offers lessons for the decarceration movement.

The deinstitutionalization movement in the United States was driven by the Mental Retardation Facilities and Community Health Centers Construction Act of 1963, signed by President John F. Kennedy in the last weeks of his life, which shifted care to community mental health centers.

Deinstitutionalization was enabled by psychotropic drugs that improved symptom management for certain disorders. The fact that psychiatric patients’ institutional care was not covered by Medicare or Medicaid upon these programs’ passage in 1965 accelerated the process. Leaving state hospitals became both possible and necessary for most psychiatric patients.

Deinstitutionalization shifted the financial burden of mental health care to the federal government, which never provided complete or long-term funding for the new community mental health centers. Less than half of planned centers were ever built, while the overwhelming majority of state psychiatric hospital beds were eliminated.

Under President Ronald Reagan, federal funding for mental health treatment was drastically reduced and block granted to states, essentially ending federal oversight of mental health care. Further billions of dollars were stripped from mental health programs by the states themselves during the Great Recession.

The legacy of deinstitutionalization has included improved rights, respectability, and community integration for many Americans suffering mental illness and those with intellectual disabilities, especially those with engaged families and more easily managed conditions.

However, it has also meant the abandonment of tens of thousands of seriously mentally ill individuals lacking sufficient social or financial supports, who face an exceptionally high risk of social isolation, homelessness, and incarceration. For these individuals, deinstitutionalization rang out like a cruel last call: you don’t have to go home, but you can’t stay here.