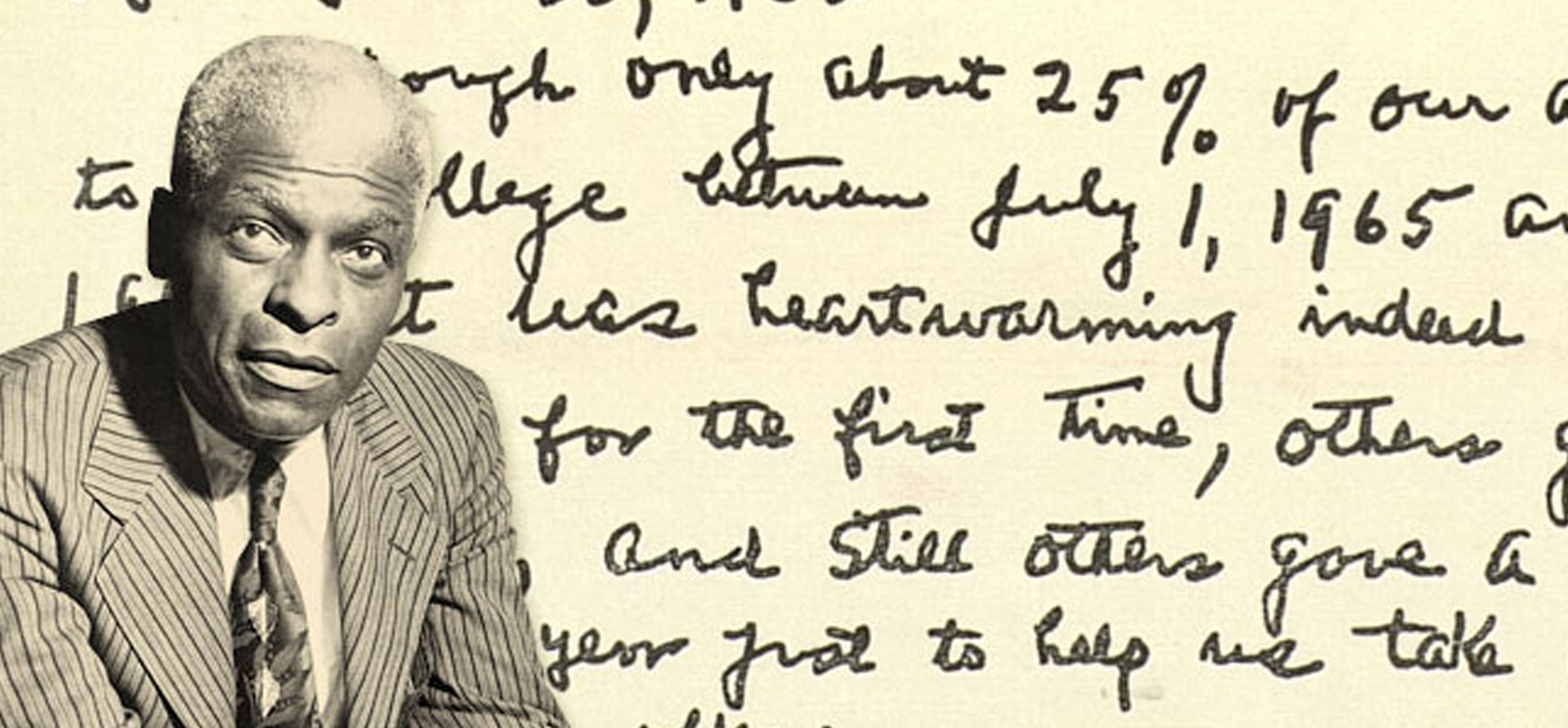

(Collage by Joy Olivia Miller; photo of Benjamin Elijah Mays and postcard from Mays to Martin Luther King Jr. courtesy Morehouse College)

Benjamin Elijah Mays, AM’25, PhD’35, was the conscience of the civil rights movement.

Benny Mays was four years old when a mob of white men came for his father. They were on horseback, brandishing rifles, and a tearful Benny took cover under a neighbor’s porch. From there he watched as the vigilantes forced Hezekiah Mays at gunpoint to remove his hat, salute, and bow.

He was fortunate to survive. Friends of Hezekiah’s were among 12 black men killed in South Carolina during the 1898 unrest known as the Phoenix riot, a terror campaign intended to frighten African Americans into political submission. “Negroes were hiding out like rabbits,” the younger Mays recalled his father saying.

Even as a boy confronted with the worst in racist violence and rhetoric, said Randal Maurice Jelks, the author of Benjamin Elijah Mays: Schoolmaster of the Movement (University of North Carolina Press, 2012), Mays took his mother’s words to heart. “Benny,” Louvenia Carter Mays used to say, “you is equal to anybody.”

Mount Zion Baptist Church, part of the religious lattice that gave southern African Americans a common foothold, reinforced his sense of worth. The Bible was Mays’s first textbook, an introduction both to theological principles and his own cultural heritage. “Early in his life—this is a kid who is really smart—he assesses that the Bible is a foundational document in the shaping of black American identity,” Jelks, associate professor of American studies and African American studies at the University of Kansas, said in an October lecture at the Divinity School. “It’s the grammar and the language that many black people use in his Baptist-dominated South Carolina.”

The church’s role in affirming his humanity and in providing social support for its members convinced Mays that the institution could be a catalyst for political change. For Mays, the motivation came from an abiding but earthbound faith, rooted in an understanding of the historical Jesus that could wrest the Bible back from those who would use it to oppress. “Jesus, in Mays’s mind, is the God-centered ethical leader who challenges the Roman state with a new set of ethical concerns about God and humanity,” Jelks said.

Some of his earliest prayers were for the education that would help him shape that worldview. Hezekiah Mays, a tenant farmer, cared only about his son’s ability to work. But Louvenia believed that, along with religion, education would be his salvation. “She literally takes the plow from his hands,” assuming Benny’s place in the cotton fields, Jelks said, freeing Mays to leave his hometown of Epworth in 1911 for the equivalent of high school at South Carolina State College in Orangeburg. He paid his train fare with a ten-dollar bill that Hezekiah threw at him in anger as he left.

Mays validated his mother’s intuition. Becoming a divinity scholar, a Baptist minister, a dean at Howard University, and president of Morehouse College from 1940 to 1967, Benjamin Elijah Mays, AM’25, PhD’35, helped to bend the arc of American history away from the segregation and mob injustice that seared his memory. He achieved such stature as both a preacher and a teacher that he became Martin Luther King Jr.’s intellectual and spiritual conscience.

As a young man, Mays felt the need to prove himself against white people, an ambition that shamed and inspired him. “It was wrongheaded of me, but I thought if I were able to compete with white people, I would be just fine,” Mays later said. “I would know that the stain of segregation would be off me.” He succeeded, graduating Phi Beta Kappa in 1920 from Bates College in Maine.

After less than a year at the Divinity School, Mays and his wife, Ellen Harvin, left Chicago so he could teach at Morehouse College. While there, he became an ordained minister at Shiloh Baptist Church. “Those three years were golden,” Jelks writes, but the period ended in tragedy.In 1923 his wife and their baby died in childbirth.

The next year, Mays returned to Chicago to complete his master’s degree. He interrupted his doctoral work to teach at South Carolina State, where he met and fell in love with Sadie Gray, PhB’24, AM’31, his second wife.

Off and on, Mays spent 14 years at Chicago. During that time he also worked for the Tampa Urban League and conducted sociological research with Joseph William Nicholson on the black church in America. In 1933, they published The Negro’s Church (Institute of Social and Religious Research). The book argues that traditional attention to “life after death” themes—a necessary focus for slave congregations to endure bondage on earth—generated insufficient “spiritual force” for the contemporary cause of equality. Instead, Jelks writes, Mays believed the church and its clergy should “empower black people to make immediate claims to their rightful civic freedoms.”

In the final year of writing his dissertation, Mays became dean of Howard University’s School of Religion. Working to the point of exhaustion, he had to be “forcibly bedridden” for months in 1934 and 1935. Still, Mays defended his dissertation with honors, insisting to his friend Howard Thurman that he wouldn’t have wanted the degree otherwise. “His manner was always humbled,” Jelks said, “but the bro had an ego.”

Mays considered himself a spiritual and intellectual leader, a voice for his people, but always of them. He wrote columns for black newspapers—the Norfolk Journal and Guide, the Baltimore Afro-American, the Pittsburgh Courier. “He thinks that ordinary black folk can know what he’s talking about,” Jelks says. “That he can translate to them this great historical moment.”

He had firsthand experience to relate. In 1936, Mays traveled to India and interviewed Gandhi. His principles of nonviolence, echoing the gospel of love that Mays considered Christianity’s only constant, provided a rhetorical bridge from the pulpit to the public square. “Long before Martin Luther King is thinking about it—he ain’t even born,” Jelks said, Mays began to shape the ideas that would define the civil rights movement in the United States.

As president of Morehouse College, Mays became forever intertwined with King, who was a student there in the 1940s. By the time King enrolled, Mays cut a regal figure on the Morehouse campus and in the wider African American community. Tall, lean, and stylish in his pinstripe suits, “he was camera ready,” says Morehouse alumnus Russell Adams, AM’54, PhD’71. Mays’s oratory, Adams adds in Schoolmaster of the Movement, elevated the black struggle with “precisely selected words lovingly and rhythmically enunciated.”

His voice resonated even in white society. In 1955, Mays was invited to address the Southern Historical Association about the Brown v. Board of Education decision on a panel that included William Faulkner. A featured speaker addressing the cause of black equality, Mays had to enter the Peabody Hotel in Memphis through the kitchen. Faulkner’s soft-spoken talk—later adapted as a Harper’s essay, “On Fear”—dominated the media coverage. But Mays, Jelks writes, “stole the moment.

His speech articulated a theme that connected Lincoln to King. “Make no mistake—as this country could not exist half slave and half free, it cannot exist half segregated and half desegregated. The Supreme Court has given America an opportunity to achieve greatness in the area of moral and spiritual things just as it has already achieved greatness in military and industrial might.”

King, only in his mid-20s when he became the nation’s most famous civil rights leader, relied heavily on Mays’s leadership example. “He also needed Mays for spiritual support as he faced the burden of being perceived as the personification of black America’s hopes and dreams,” Jelks writes. “It was Mays who held the job as King’s consigliere over the next fourteen years as the death threats against him grew more ominous and the public battles more dangerous.”

Those battles also grew more fruitful in the cause of freedom. Where they were won, victories could be traced to the social theology Mays had advocated for decades. But casualties continued to mount, so the war raged on against the forces of discrimination and, increasingly, within the civil rights movement itself. “Some activists viewed nonviolent strategies as being unrealistic in light of the outright terror that had been organized against them,” Jelks writes.

Mays suffered the toll of that violence; it had terrorized his father and, on April 4, 1968, killed his “spiritual son.” King’s assassination, Jelks notes, became “the proverbial last straw for critics of nonviolent religious social activism.” Called upon to deliver the eulogy for the man he had hoped would give his own, Mays held firm to his belief in the futility of retribution.

He urged an audience at Morehouse College not to “dishonor [King’s] name by trying to solve our problems through rioting in the streets.” If they could turn their sorrow into hope for the future and use their outrage to invigorate a peaceful climb to the mountaintop, “Martin Luther King Jr. will have died a redemptive death from which all mankind will benefit.”

King advanced the cause of equality beyond what Mays might have imagined possible, an undeniable validation of his example. But his devastation over King’s death, a tragic reprise of the white-supremacist rage he witnessed as a boy, tempered any pride in the progress he inspired.

Although African American life and liberty were not yet fully accepted civil rights, Mays found comfort in the resolute claim to freedom that the movement asserted against a society that would not grant it. “No man is really free who is afraid to speak the truth as he knows it, or who is too fearful to take a stand for that which he knows is right,” Mays said. “Every man has his Gethsemane.”

Updated 03.07.2013 to reflect a correction noted in Letters (Mar–Apr/13).