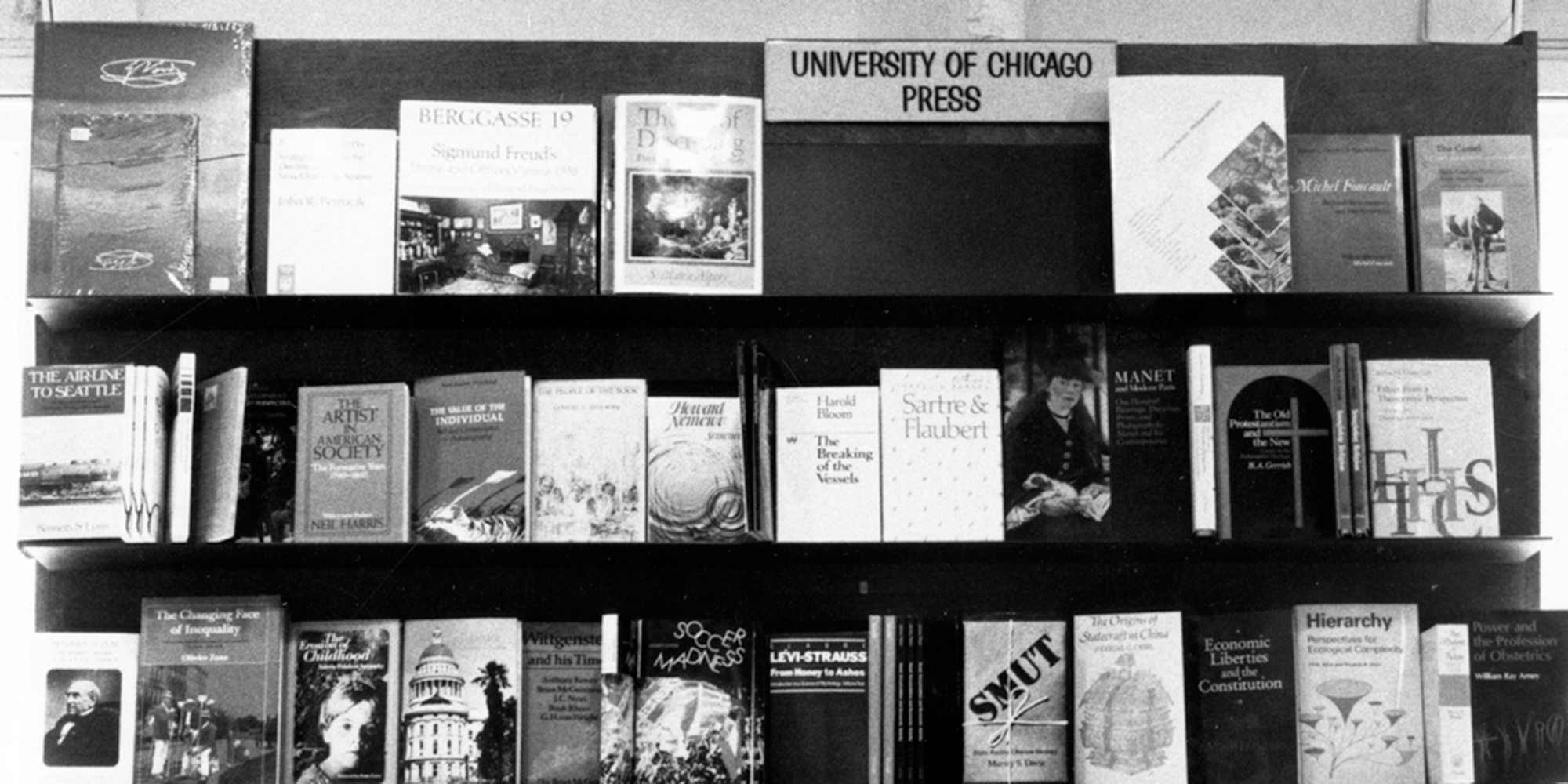

(UChicago Photographic Archive, apf7-02633r, University of Chicago Library)

Science and emotion in A Wrinkle in Time.

Last spring Madeline L’Engle’s classic novel A Wrinkle in Time was timely again, thanks to Disney’s Oprah-starring film adaptation. Published in 1962, the book tells the story of Meg Murry, the gifted but troubled child of two scientists who travels (or, in the language of the novel, “tessers”) through space-time to rescue her physicist father from an alien intelligence known as IT. The novel provided a leaping-off point for a May panel discussion at the Seminary Co-op Bookstore about women in science, feminist physics, and multiple other topics.

The panelists were Chloe Lindeman and Joohee Bang, both finishing their first years as graduate students in the Physical Sciences Division; Sophia Vojta, AB’18, then a fourth-year majoring in physics and Fundamentals: Issues and Texts; and Tamara Vardomskaya, PhD’18, a linguist who writes science fiction and fantasy. “I did do a math degree when I was an undergrad,” she noted.

The following, which barely scratches the surface of their wide-ranging conversation, has been edited and condensed.

Reading and rereading

Bang: I first read A Wrinkle in Time when I was 11, in Korean.

Vojta: I also first read this novel when I was quite young, probably about eight or nine. I’ve read it in English and German. I tried to read it in French once. That was a mistake. But this was a very formative novel for me.

Lindeman: I have only read this novel in English. I must have read it as a kid—I remember a couple of scenes—but I just read it in these past couple of weeks, so it’s still very fresh in my mind.

Vardomskaya: I actually read the other two volumes, A Wind in the Door and A Swiftly Tilting Planet, when I was about 11 or 12, and I only read this book a couple of years ago. I just reread it a couple of days ago.

Women in science

Lindeman: There are so many prominent female science-related figures in the novel. Mrs. Murry is the most obvious one. She’s actually my favorite character because certainly in that time and even today, the idea of having a career and also having a family can be really difficult. And she combines these two things in an interesting way. She has her lab in her home, in her garage. She makes it work. Even as her partner is gone for several years, she’s able to create this life where she has a family and also is doing her work as a scientist. They’re not distinct for her. Her family is also her science life.

Vojta: I wanted to know more about her: Tell me about your bacteria. I want to know about your work. While I agree that this character encapsulates something powerful about the necessary relationship between family and work, I wish that we had seen more of the work.

Science and emotion

Lindeman: Meg breaks down into tears a lot. She’s a child, but some people have seen this as the author’s bias—that women tend to react this way more than men. One of the very few female physics professors at Haverford College, where I did my undergrad, posted an article on her door about a woman who cried at her thesis defense. It was an extremely stressful experience, and that’s OK. That doesn’t make you any less of a scientist. Everyone has emotional responses to things. That’s not something we can get rid of.

Bang: I was a history major before I transitioned to chemistry and then physics. When my friends and family heard that I’d made that decision, they felt I didn’t really fit in this realm because I was really emotional, and that meant I wasn’t the type of person who could study things that require reason and logic. But I don’t think emotions and thinking about things in a rational way are the opposite of one another.

Vojta: We have this idea that science is objective and that we’re in pursuit of a beautiful, pristine truth, and that perception and personal investment has nothing to do with what we see in a scientific experiment. I think that’s a faulty idea both in terms of what you choose to study—science is often about studying that weird thing you’re obsessed with—but also in terms of what you see when you look at an experiment. I think there’s an intrinsic connection between our emotions and our way of perceiving. Whether that’s a problem for science or not is a different question. But I don’t think they’re separable from one another.

Vardomskaya: There was a study of a person who had suffered a type of brain damage that shut down his emotions. He was completely rational. You would expect he was like Mr. Spock. But it turned out that it took him three hours to decide what he was going to have for lunch. You need your emotions to make decisions. You need emotions to figure out what to focus on. “I feel good about having a sandwich, therefore I’m going to have a sandwich.”

Reading list

We asked you what stories inspired your interest in science. Here are some of your answers.

- A Canticle for Leibowitz by Walter M. Miller Jr.

- Bloodchild and Other Stories by Octavia Butler

- Doomsday Book by Connie Willis

- Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions by Edwin A. Abbott

- Frankenstein by Mary Shelley

- Oryx and Crake by Margaret Atwood

- Snowball Earth: The Story of a Maverick Scientist and His Theory of the Global Catastrophe That Spawned Life as We Know It by Gabrielle Walker

- "The Comet" in Darkwater: Voices from Within the Veil by W. E. B. DuBois

- The Curse of Chalion by Lois McMaster Bujold

- The Left Hand of Darkness by Ursula K. Le Guin

- The Mismeasure of Man by Stephen Jay Gould

- The Soul of a New Machine by Tracy Kidder

For more recently written recommendations, check out the following books:

- Binti by Nnedi Okorafor

- Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress by Stephen Pinker

- Reading Lucretius in the Renaissance by UChicago historian Ada Palmer