Through constant experimentation in the Laboratory Schools, the College, and the graduate programs, University of Chicago educators and scholars have tested and spread innovative ideas about how best to teach and to learn.

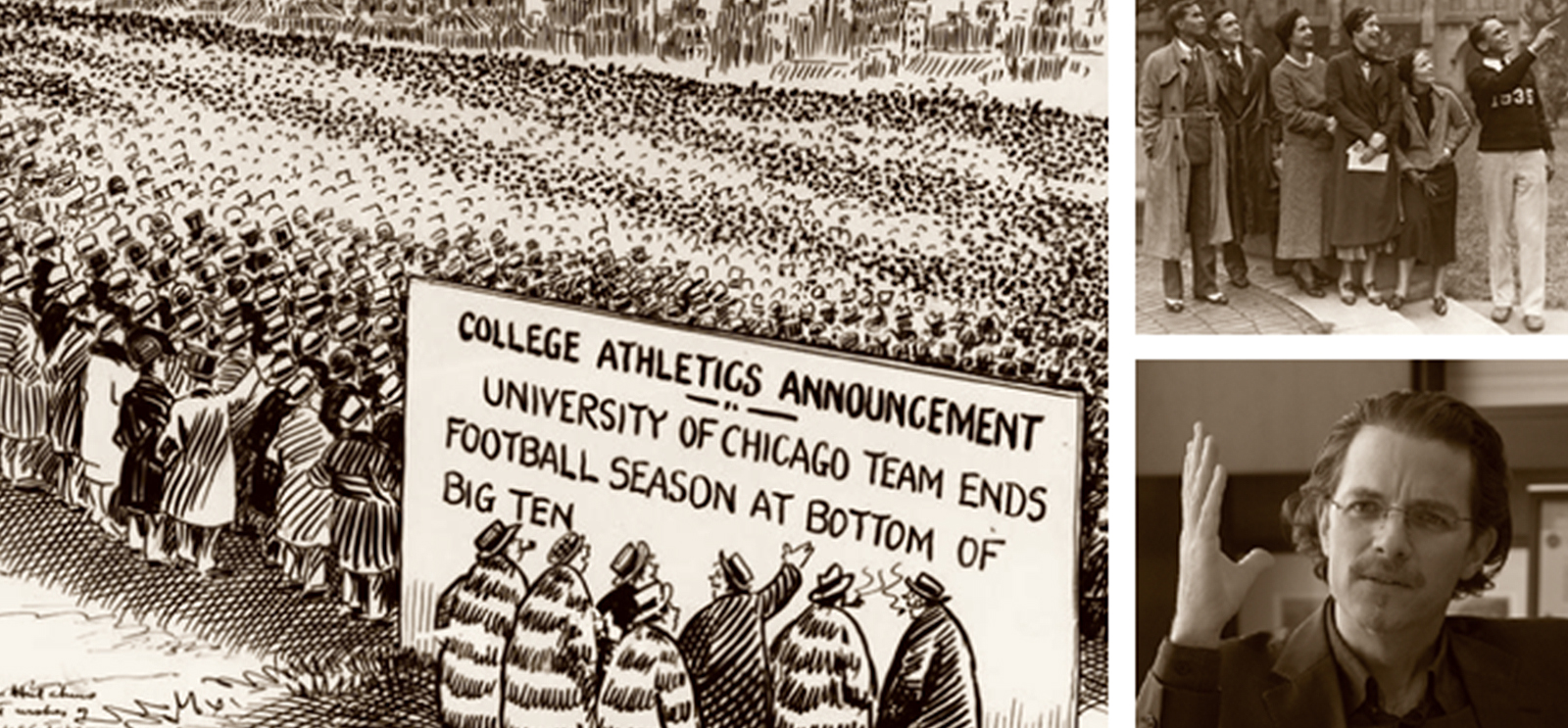

Even if only to cast scorn, humans are drawn to the new and unknown. We hang around and watch, in case it really is the eve of revolution.

So when John D. Rockefeller, an oil king with dreams of a Baptist university in the Midwest, and William Rainey Harper, a young Hebrew scholar well on his way to academic celebrity, opened a “bran splinter new” university on a swampy piece of Chicago’s South Side in 1892, the skeptics came to poke around. So did the students.

What they found was indeed a new kind of American university, one that promised opportunities for advanced research with some of the best minds in the country and an undergraduate College where young men and women could continue their education and get a taste of true scholarship. Initially dismissed by Harper’s fellow Baptist educators as wild and unfeasible, his plan for a combined graduate and undergraduate university with courses offered year-round soon became a model for future institutions.

Harper’s University signaled a shift in American education. In the previous century, serious scholars traveled to Germany to study with leaders in the social, physical, and biological sciences and in the humanities. Most American institutions by contrast were marked by patriarchal professors teaching rote memorization. Harper wanted to infuse the stuffy American lecture hall with the excitement and prestige of the German institution, where professors did important research, held interesting seminars, and ran scientific laboratories. Although Harper’s interest in research meant that in cases of conflict the laboratory won out over the classroom, his early commitment to student dormitories and to an experimental elementary school showed his dedication to a holistic academic experience.

If graduate research was first chair in Harper’s mind, his university model could also thrust undergraduate education to the front of the class. As the 1920s roared to an end, the faculty grew concerned about the academic caliber of the College, prompting Dean Chauncey S. Boucher to develop the University’s first core curriculum. And as enrollment waned and financial woes beset the University in the 1950s and again in the 1970s, several presidents were reminded that the incoming first-years were paying the bills. The efforts to refine and maintain this balance constitute one of the most spirited debates in the University’s history, one that continues today.

1892

The University’s first president, William Rainey Harper (above), snatches faculty from universities across the country and establishes a new model for graduate education. Undergraduates, meanwhile, will divide their years between general study meant to create “men of service” and specialized work in the divisions.

1895

John Dewey (above) heads both the Department of Philosophy and a new Department of Pedagogy, whose aim is “to train competent specialists for the broad and scientific treatment of educational problems.”

1896

Dewey opens what’s now called the Laboratory Schools, in a house on 57th Street with 16 students, crafting his lessons on the child rather than the subject matter. The elementary school is a workshop for observing students and for testing educational methods.

The College’s first graduating class includes an African American woman, Cora Bell Jackson.

1898

Precursor to the business school, the College of Commerce and Politics offers courses on business practices to undergraduates.

1901

Sophonisba Breckinridge (above) is Chicago’s first woman PhD; in 1904 she becomes the Law School’s first female grad. Focused on the “great social issues of the day,” she goes on to lead the School of Social Service Administration.

The Chicago Institute, a teacher training program led by progressive educator Francis Parker, moves to the University.

1902

Dewey’s high school joins with the Manual Training School and the South Side Academy to become University High School. The 500-student school is soon known as the Midwest’s best.

The Law School opens in the former University Press Building (now the bookstore building). With an annual tuition of $150, the Law School is the first US institution to grant exclusively a JD (rather than both a JD and an LLB).

1909

Charles Hubbard Judd becomes director of the School of Education, chair of the Department of Education, and the director of the Lab Schools. Judd, who had been head of the psychology lab at Yale, focuses on educational psychology and testing.

1916

William Scott Gray, PhB’13, receives his PhD in education, writing one of the first ever reports on elementary-school reading performance: Studies of Elementary School Reading through Standardized Tests. Gray goes on to conduct more research in the Lab Schools (above), serve as dean of the education school, and later coauthor the Dick and Jane reader series.

1919

Lab Schools superintendent Henry Clinton Morrison champions teaching in units, with the goal of having a student understand a subject rather than memorize information. In The Practice of Teaching in the Secondary Schools (1931), which popularized the unit mastery concept nationwide, he cites a unit example: “How people live in the hot, almost rainless, country along the Nile.”

1923

The College holds its first orientation week for incoming first-years before the autumn quarter to introduce the new students to the neighborhood and the academic community.

1927

Dedicated on Halloween, Billings Hospital is home to the University Clinics, led by Franklin C. McLean, who calls for a full-time staff of teachers and researchers rather than using physicians as part-time instructors.

1929

Yale Law dean Robert Maynard Hutchins (right) is elected president of the University.

The $400,000 Sunny Gymnasium opens at the Lab Schools, underscoring the importance of physical education for youth.

1930

Hutchins proposes and the trustees adopt a reorganization that the Magazine calls “as significant—in terms of the whole picture of higher education in America—as the very founding of the University.” The structure? The College, four divisions in arts and sciences, and the professionals schools. The objectives? “To promote cooperation in research, to coordinate teaching, and to open the way to experiments in general higher education.”

1931

The experiments begin. Dean of the College Chauncey S. Boucher implements the New Plan: two years of gen-ed courses followed by specialized study. Students advance through a “self-pacing system” of comprehensive field examples. Taking the course is optional.

1939

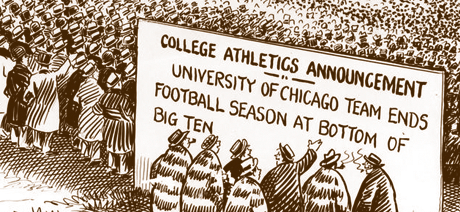

President Hutchins eliminates Big Ten football, unwilling to sacrifice academic standards to recruit better players.

1942

Hutchins and dean of the College Clarence Faust, AM’29, PhD’35, launch a heavily prescribed College curriculum, starting after two years of high school and focused almost exclusively on the social sciences and the humanities. High-school graduates who take electives in their chosen division in addition to a reduced general-education curriculum can earn an alternate PhB degree.

1944

The College approves a general mathematics requirement and, the next year, a foreign-language requirement.

1958

Under President Lawrence A. Kimpton, a committee proposes a “new College” including two years of general education and two years of specialization. The faculty’s approval signals a compromise between the divisions and the College—and thus between the new plan and the Hutchins College—that brings the two closer together through joint appointments and mutual responsibility of awarding the AB.

1959

The new Law School building, designed by Eero Saarinen with the library at its center, opens. Vice President Richard M. Nixon gives the dedication address.

The School of Business, which phased out its undergraduate program in 1942, gets renamed the Graduate School of Business.

1961

Almost three decades after Hutchins closed the School of Education, a new Graduate School of Education puts the University back in the business of training teachers.

1962

Christian Mackauer, the William Rainey Harper professor of history in the College, gives incoming first-years the first Aims of Education address, discussing the tensions between general and expert knowledge.

1966

Provost Edward Levi, U-High’28, PhB’32, JD’35, implements a system of multiple colleges, now the Collegiate Divisions, to prepare the College and the divisions for considerable enrollment growth—a cornerstone of a plan for reinvesting in the University.

1978

UChicago historian Hanna H. Gray becomes the University’s president, the first woman president of a major research university.

A national glut of teachers prompts the University to close the Graduate School of Education. Remaining faculty and students merge with the Department of Education.

1979

UChicago math professor Izaak Wirszup presents his National Science Foundation–sponsored report showing the Soviet Union ahead of the United States in math and science education. The report gains national attention and, on the eve of an election year, pushes education reform into the political spotlight.

1984

Common Core becomes official College lingo. The revised curriculum splits a student’s course load equally in two: 21 courses of general education and 21 courses of specialized study in a division.

1988

The University’s Center for Urban School Improvement launches, aiming to contribute to better Chicago public schools.

The University’s Office of Technology and Intellectual Property commercializes the Everyday Mathematics curriculum developed by Wirszup and the University of Chicago School Mathematics Project.

1990

The Consortium on Chicago School Research forms, joining together researchers from the University, Chicago Public Schools, and others to study reforms that decentralized the city’s schools. The data-guided consortium continues to study CPS reform efforts.

1996

The University announces its plan to phase out the Department of Education by 2001, citing inadequate scholarship standards. Provost Richard Saller says the University will “preserve what is most vital in the department,” such as the Center for Urban School Improvement.

1998

The College faculty revises the Common Core, splitting it evenly between general-education requirements, specialized study courses, and electives. Critics complain about fewer Core courses being required.

1998

The Center for Urban School Improvement opens the first University of Chicago Charter School campus, North Kenwood/Oakland Elementary School, on East 46th Street to provide quality education for urban families and professional development for teachers.

2003

The Urban Teacher Education Program master’s-degree program begins, training students to work in Chicago Public Schools.

2005

The interdisciplinary Committee on Education opens in the Social Sciences Division, chaired by Steven Raudenbush, the Lewis-Sebring distinguished service professor in sociology and the College.

2008

The University opens the Urban Education Institute. It now oversees four charter school campuses, the Consortium on Chicago School Research, the Urban Teacher Education Program, core functions of the Center for Urban School Improvement, and efforts to develop educational tools.

2009

Research by the Consortium prompts officials at the US Department of Education to simplify the FAFSA form required for students seeking federal college aid. The revised form allows students to bypass nonapplicable questions and helps parents import their federal tax information.

2010

The Consortium publishes Organizing Schools for Improvement (University of Chicago Press), a study identifying five elements—effective leaders, collaborative teachers, involved families, a supportive environment, and ambitious instruction—essential for successful schools.

September 22, 2011

Bernard Harcourt, the Julius Kreeger professor of law and chair of the Political Science Department, gives the Aims of Education address to the Class of 2015. Harcourt’s topic: “Question the Authority of Truth.”