(NASA GSFC_20171208_Archive_e001592)

A new institute confronts climate change and economic growth as closely linked challenges.

Introducing the University’s Institute for Climate and Sustainable Growth at an event this past fall, economist Michael Greenstone, LAB’87, laid out the institute’s challenge in stark terms: “The world does not have an example of a society becoming wealthy, and all the comforts that come along with that, without consuming lots and lots of energy.” Greenstone, the Milton Friedman Distinguished Service Professor in the Kenneth C. Griffin Department of Economics, the Harris School of Public Policy, and the College, has directed UChicago’s Energy Policy Institute (EPIC) since 2014 and now leads the new institute as its founding faculty director. Whether in rural India or right here in Chicago, “there are families that aspire to better lifestyles for themselves and their children,” he said—“and that runs through increased energy consumption.”

The problem? Fossil fuels, which largely remain the cheapest way to meet those energy needs, are damaging lives, livelihoods, and the planet.

With Greenstone delivering his remarks in front of a large window overlooking the Midway, the 77-degree day in late October could hardly escape his listeners’ notice, or his own comment. But, he reminded the crowd, data of all kinds show that climate change is “not just the more pleasant fall in Chicago.” India, for one, now experiences summer days over 40 to 45 degrees Celsius—104 to 113 degrees Fahrenheit—“and that impairs people’s lives in very consequential ways.” Crops fail, people can’t work, people die prematurely. The world over, extreme weather events are becoming more typical and more widespread.

Such downstream effects of the 1.3 degrees Celsius rise in Earth’s temperature since the Industrial Revolution, Greenstone said, are one of the twin challenges the new institute will take on, along with the world’s ever-persistent need for economic growth.

“So it’s these two ideas,” he said, “climate and growth. And the question: Must they really be in conflict with each other?” Animating everything the new institute will do is a deeply held belief that a balance must be struck; that at the intersection of technology, economics, and policy are solutions that will address both challenges; and that UChicago has the people and knowledge to find those solutions.

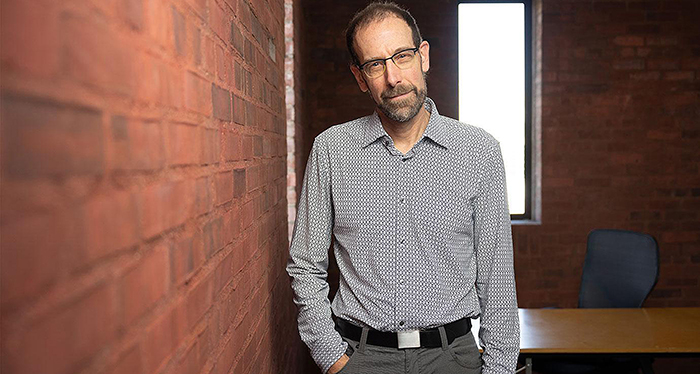

October 30 launch of the Institute for Climate and Sustainable Growth. (Photography by Jason Smith)

The October 30 launch of the Institute for Climate and Sustainable Growth was a major event. Over the afternoon, Greenstone was joined at the Rubenstein Forum by UChicago’s president and provost, the institute’s other faculty leaders, experts and policy makers from the developed and developing worlds, and Illinois governor J. B. Pritzker and senior senator Dick Durbin (D-IL). Throughout the day, a career fair allowed students to better understand different climate and energy career paths, while a “climate showcase” of research programs and organizations and a student poster display demonstrated some of the work already underway.

In opening remarks, President Paul Alivisatos, AB’81, elaborated on why this institute, these challenges, and this moment are the right ones. The climate problem, he said, has inspired research centers at institutions everywhere—all needed efforts. In launching the Institute for Climate and Sustainable Growth, UChicago is building on its particular strengths.

On one hand, Alivisatos said, that means building on a long track record of “applying economic and policy-based thinking to tackle major societal challenges.” Greenstone and his EPIC colleagues have done that in the climate and energy arena through innovations like the world’s first pollution market, in the Indian state of Gujarat, and the Air Quality Life Index, which quantifies the impact of air pollution concentrations on life expectancy. Economics and policy work is one of the institute’s three research pillars.

Another singular strength of UChicago is a deep bench of scientists working at the cutting edge of energy storage technology. Between the Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering (PME) on campus and the intertwined research of Argonne National Laboratory nearby, managed for the US Department of Energy by UChicago, “we are home to one of the nation’s largest concentrations of energy innovators,” Alivisatos said. This is the institute’s second research pillar. Its Energy Technologies Initiative (ETI) seeks the storage solutions needed to create a cleaner energy infrastructure at scale. ETI’s work is led by PME professor Y. Shirley Meng, who has spent her career seeking and finding better materials and methods for storing energy—better batteries, to be succinct.

The institute’s third research pillar creates a new field of study: climate systems engineering. The field has developed “as a hedge against the unwelcome possibility that large-scale interventions may be needed,” Alivisatos said at the launch—in the event that efforts to systemically reduce carbon emissions and mitigate climate change run out of time. These interventions might include some method of removing carbon from the atmosphere, local efforts to protect melting glaciers, or using particles in the atmosphere to reflect the sun’s light. University professor of geophysical sciences David Keith, an internationally acknowledged leader in this area who joined UChicago in 2023, is the founding faculty director of the institute’s Climate Systems Engineering Initiative, which will explore such measures and seek to thoroughly understand their potential risks and benefits.

Economics and policy, energy storage, climate systems engineering: These areas, where the University of Chicago is especially well positioned to contribute, form the research foundation of the Institute for Climate and Sustainable Growth. In its leaders’ vision, cross-disciplinary research will take root between and beyond the central pillars, and with it the potential to generate the next big climate ideas. Just as central to its mission is the institute’s novel vision for education.

“The world needs a generation of thinkers and special people who can set the pace,” Alivisatos said at the launch. It needs individuals, especially those just setting out into higher education, “who can see the climate challenge from its many angles, appreciate the societal and economic complexities, understand what is required technically—and even politically—to confront these problems.” To that end, in September 2025, the University will introduce the Chicago Curriculum on Climate and Sustainable Growth.

The curriculum will provide “a road map for educating an entire generation of leaders, thinkers, and entrepreneurs on the seminal challenge of our time,” in the institute’s words. Law professor David A. Weisbach is leading development of the curriculum, which is grounded in eight required courses and offers specialized concentrations (see “The Chicago Curriculum,” below ). Over time, the institute’s leaders expect that the curriculum will be adopted at other institutions around the world.

Speaking to the need for the curriculum, Greenstone recounted his experiences talking to college-age US students about climate change. “There’s a little reeducation that has to go on,” he said. Many “have a very one-sided view of the climate and what I like to think of as the climate and growth problem, and in truth, they haven’t lived—they may have visited, but they haven’t lived—in a place where incomes are very low or energy consumption is very low.” The new curriculum will give “a real 360-degree perspective” including climate and energy law, science and technology, international perspectives, impact and adaptations, and humanistic perspectives on the relationship between human beings and our planet.

Bringing it all together in students’ fourth year will be an experiential course. Greenstone envisions it bringing students to places where, in different ways, climate matters most in people’s daily lives: to rural India to see “what it’s like to live with a couple-hundred kilowatt hours of electricity”; to west Texas to witness “what a booming fracking town looks like”; to Wall Street to meet with investors; and to Washington, DC, to talk to policymakers. The broad training that precedes this capstone course will have given students “the tools to hold these multiple competing thoughts in their heads.” Overall, the curriculum aims to “produce better leaders and better citizens.”

Groundbreaking climate and energy research is nothing new at UChicago. EPIC, the institute that Greenstone has led for a decade, has had tangible impact on measuring, educating about, and ameliorating the effects of climate change. UChicago geophysical scientists, chemists, and physicists have long contributed to our understanding of the atmosphere and the effects on it of carbon dioxide buildup.

But the particular approaches that come together in the new institute are uniquely wedded to this moment and this university—and, its leaders believe, are uniquely potent.

In their vision, the Institute for Climate and Sustainable Growth is an all-UChicago endeavor. Early in the planning, Greenstone told the launch event audience, University and faculty leaders conducted a “listening tour” across campus that revealed deep and avid interest.

As well as engaging the 150 or so current faculty who raised their hands, the institute will hire 20 new faculty members over the next five years. Searches are underway now for positions in law, political science, economics, materials science, and artificial intelligence. “The institute’s interdisciplinary, collaborative approach is crucial for addressing the complexities of climate change,” said Provost Katherine Baicker at the launch. “It will create a dynamic platform that engages the full breadth of insights across our campus community.”

The Chicago Curriculum

Available beginning in Autumn Quarter 2025, the Chicago Curriculum on Climate and Sustainable Growth builds on eight foundational courses that grapple with the climate and sustainable growth challenge from multiple perspectives:

- Climate Science

- Climate and Energy Economics

- Politics and Law of Energy and Climate

- Energy Technology and Energy Systems

- Humanistic Approaches to the Climate Problem

- Climate Impacts and Adaptation

- International Perspectives on Energy and Climate

- Global Perspectives

Y. Shirley Meng

At UChicago since 2022, Y. Shirley Meng is known for her innovative approaches to discovering better battery materials—a prerequisite to moving away from fossil fuel use. Bringing quantum mechanics and supercomputing to bear on the quest for ways to safely and reliably store more energy, Meng, faculty director of the institute’s Energy Technologies Initiative, has made key discoveries in rechargeable batteries for electric vehicles; power sources for the Internet of Things, all the connected devices we use every day; and grid-scale energy storage.

This past September the US Department of Energy selected Argonne National Laboratory to host a new research hub, the Energy Storage Research Alliance (ESRA), and selected Meng to direct it. Nearly 50 researchers from three national labs and 12 universities, including UChicago, will come together at ESRA to address pressing battery challenges.

David Keith

As faculty director of the new institute’s Climate Systems Engineering Initiative, David Keith builds on more than 25 years exploring potential technological interventions to reduce the effects of climate change, an approach that he articulated and advocated for in his book A Case for Climate Engineering (MIT Press, 2013). He studies policy related to climate and energy, for instance analyzing electricity markets and carbon prices and investigating how the public perceives risky geoengineering measures.

Also an engineer, Keith has built hardware including the first interferometer for atoms, a high-accuracy infrared spectrometer for NASA’s ER-2 aircraft, and a stratospheric propelled balloon for solar engineering. In 2009 he founded Carbon Engineering, a company developing technology to capture CO2 from ambient air.