Mark Bouman (center) and students hike up the Succession Trail at Indiana Dunes National Park on a windy April day. (Photo courtesy Jessica Landau)

Students in the Calumet Quarter program learn about the complicated, jolie laide region just south of Hyde Park.

Friday is field trip day.

In Paris, where UChicago runs more than 20 different study abroad programs, Friday is the day for excursions. It’s field trip day in the Calumet, too, because the Calumet Quarter was modeled after study abroad.

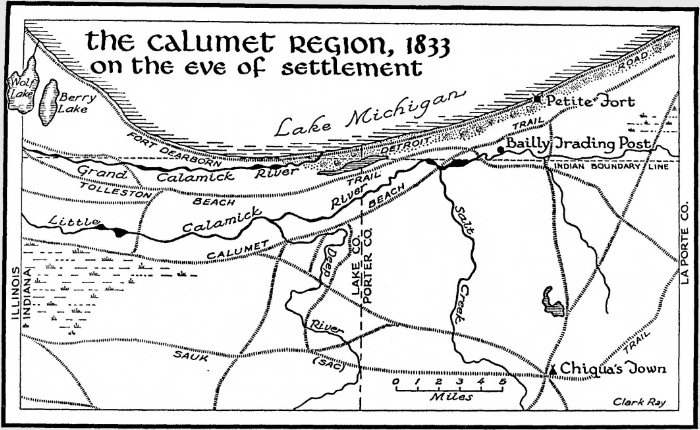

The Calumet Region—the name means “pipe” in French, a reference to ceremonial pipes used by Native Americans—is not far. It begins less than ten miles south of Hyde Park and runs into northwest Indiana. As for its exact borders, “It’s a great question,” says Mark Bouman, a scientist at the Field Museum and one of the Calumet Quarter’s three instructors. He gives a long, complicated, geographer’s answer—but the short version is, there is no one answer.

An easier way to understand the Calumet Region is to list what’s in it. The Calumet includes the city of Gary, Indiana (population 67,000, one-third its peak size in 1960). It includes the Indiana Dunes, a region that’s split up among the Indiana Dunes State Park, the Indiana Dunes National Park, and lots of private property. There are working steel mills and other heavy industry in the Calumet, as well as million-dollar lakefront homes. “A patchwork of ownership,” as Bouman describes it.

The Calumet is also home to more than 1,500 species of plants across a remarkable diversity of ecosystems. In fact, the entire notion of an ecosystem developed out of important early research by botanist Henry Chandler Cowles, PhD 1898, on the plants in the Dunes.

The Calumet is a fascinating, contradictory, imperfect, sublime part of the world. This past Spring Quarter, 13 College students signed up to study it.

The first Friday of the quarter, the students went on an introductory tour to the Calumet, which was titled “The good, the bad, and the ugly.” On another Friday, they toured Pullman, the planned community on the far South Side where Pullman railcars were once built. On another, they visited Gary and met the mayor. On another, they saw the Metropolitan Water District’s Deep Tunnel system, 300 feet underground.

This particular Friday trip, to the Indiana Dunes, began the night before. The students went camping (arguably, glamping) at the Dunes Learning Center—on a campground built by US Steel in the 1940s for the families of its workers. The students slept in sleeping bags, but the cabins were heated and had hot running water.

Despite, or possibly because of, these comfortable quarters, most of the students agreed to go on an optional nighttime hike led by Bouman. Even though it was raining. “It’s amazing what you can see at night,” he says. One of the students had never been on a hike before.

The next morning, after breakfast in the Cowles Lodge (named for the UChicago botanist), the students pile onto a small bus, driven by a woman who cheerily introduces herself as Mona. The other Calumet Quarter instructors—geographer Mary Beth Pudup and art historian Jessica Landau—are on the tour, too, as is instructional assistant Derick Anderson.

The first stop of the day: the Indiana Dunes Visitor Center, which recently added a trail, the Indiana Dunes Indigenous Cultural Trail, on donated land.

The Dunes is the number one tourist destination in Indiana, says Christine Livingston, the center’s director. With O’Hare and Midway Airports so close, it is the “easiest national park to access,” she says. The area has a complex, interesting story that’s “very undertold.”

To develop the trail, she worked with the Potawatomi and Miami, as well as Indiana Dunes Tourism and the Indiana Dunes National Park. She was warned that “the tribes are difficult to work with,” but her experience was “absolutely the opposite,” she says.

The tour concludes with a quick look at the trail, which is still in progress; its design reflects the tribes’ values and insights. As just one example, the murals include local animals such as sandhill cranes and river otters—but no white owls, which are seen as harbingers of death. “We had a mural of an owl, actually,” Livingston says. “So we have repainted all of our murals.”

The students are clearly impressed with Livingston’s efforts to include everyone in the decision-making. “I will never cut a museum slack ever again,” one student says as they board the bus.

The next stop is the Indiana Dunes National Park, which, confusingly, wraps around the Indiana Dunes State Park.

The bus stops to let a freight train pass. “It’s one of the most dangerous crossings in the region,” observes Paul Labovitz, past National Park superintendent, the host for this segment of the tour.

Mona knows where she’s going, but for many visitors, just finding the park is a challenge. Considering the heavy industry surrounding the park, and no obvious boundaries, you might well ask, “‘Where are you taking me? Into the mill?’” says Labovitz. “You’d think, ‘None of this makes sense to me.’”

Labovitz, who retired last year after more than 35 years with the Park Service, wears a green Indiana Dunes National Park jacket and a pair of binoculars around his neck. Throughout the tour, he supplies a steady stream of facts, anecdotes, jokes, and sarcasm.

The Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore was established in 1966. It became a national park in 2019, which “changes nothing and everything.” The number of visitors doubled. The funding did not change. “Soap and toilet paper will break you,” he observes.

Labovitz and Bouman lead the group on a short walk down to West Beach. The Chicago skyline is tiny in the distance, like the view from Promontory Point in miniature.

“But on that side it’s terrible,” a student remarks as she shoots a photo of the Burns Harbor plant. The park’s neighbor to the east is the last integrated steel mill built in the United States, Bouman explains. It opened in 1964 as part of a park compromise. “They bulldozed five miles of high dunes right here,” he says matter-of-factly.

“I was thinking about sacrifice zones,” Anderson remarks. In Pudup’s course, Environmental Transitions and Unnatural Histories, the students learned a host of useful—if depressing—terminology.

- Sacrifice zones: Populated areas that have been heavily environmentally damaged.

- Wastescapes: “Landscapes on the margins, wounded spaces, garbage graveyards, or derelict sites,” as described by one of the course readings.

- Superfund site: A contaminated area requiring long-term cleanup, according to the EPA. “The wastescapes of wastescapes,” as Pudup describes them in class.

- Drosscapes: Former wastescapes reclaimed for new uses. Steelworkers Park, built on the former US Steel site in southeast Chicago, is one example.

It’s a chilly, blustery day. One student pulls his arms out of his fleece and hugs his torso. Another chucks a rock into the rough waves.

Bouman points out a plaque with a famous quote from Senator Paul H. Douglas (D-IL; formerly a UChicago economics professor): “When I was young, I hoped to save the world. In my middle years, I would have been content to save my country. Now I just want to save the dunes.” It was Douglas who introduced the controversial bill to establish the Indiana Dunes National Monument in 1958.

The group turns and heads up the Succession Trail, named because the walk is an astonishing real-world demonstration of ecological succession—all in about 25 minutes.

“The point of this trail,” which includes a series of wooden staircases, “is to walk you through the successional phases,” Bouman explains. The beach is bare sand. Farther back from the water, “grasses start to fix the sand in place, and soil slowly accumulates.” After that, “you start to get the colonization of shrubs and then trees, and by the time you get to the top of the dune, you’re in a forest.” This was what Cowles was describing in his landmark dissertation, “An Ecological Study of the Sand Dune Flora of Northern Indiana.”

“I’ve been learning about ecological succession since middle school,” one student remarks. “I never knew it was discovered here.”

As they make their way up the trail, Pudup, Landau, and several of the students constantly stop to bend over plants with their phones—not to snap photos, but to try to identify them. Although it’s only 15,000 acres, the Indiana Dunes is one of the top five national parks for biodiversity, Labovitz says, rivaling the much larger Great Smoky Mountains.

The motley collection of plants along the trail grow in unlikely juxtapositions: a prickly pear cactus next to an Arctic bearberry, for example. “Botanically,” says Bouman, “it’s doing what the rest of the region is doing.”

After a bag lunch the group gathers in an area sheltered from the wind to hear Labovitz talk/joke/rant about the National Park and its neighbors: “You don’t expect to see this kind of wild place tucked in between residential homes and heavy, heavy industry.”

A few years ago, there was a fish kill. “If you know anything about fish,” Labovitz says, “when you see dead catfish, you should really worry.”

Industries in Indiana are given permits that specify how much cyanide, benzene, hexavalent chromium, and so on they can discharge into the waterways. The waterways in the Calumet flow into Lake Michigan, which happens to be the source of Chicago’s drinking water. In Indiana they talk of “permit exceedances,” Labovitz says, then translates: “It’s a spill.” And when it comes to spills, Indiana is a “self-reporting” state.

“Every tributary going into Lake Michigan from Indiana is brown,” Labovitz says. “The lake is a beautiful blue, right? Until it’s not. When is that? Five years? Five hundred years?”

Despite his exasperated tone, “I’m not a tree hugger by any stretch. I’m a business guy.” He wants the industries of northwestern Indiana to do well, but “we don’t want them to kill us and Lake Michigan in the process.”

Labovitz doesn’t mince words about the National Park’s other lakefront neighbor, either: Ogden Dunes, an affluent residential area to the west. When lake levels rose, residents wanted to construct a barrier to protect their homes. The National Park fought them in court and lost. Two acres of coastal wetland were destroyed “to protect private houses that someday will get washed away by the lake,” Labovitz says. “The lake always wins.”

Lake Michigan naturally rises and falls, he says, and these changes are “best handled by the natural coastline” rather than a rock barrier, which just accelerates erosion at either end. Lake levels have numerous long-term cycles: “a 30-, 60-, 150-, and 1,500-year cycle,” he says. “Even sunspots somehow affect the water levels in the Great Lakes. I’ll pause a moment while your head explodes.

“We have no control over lake levels. None,” he says, adding, “You couldn’t give me a house on Lake Michigan.”

Back on the bus (Landau spots a coyote running along the edge of the highway) the students meet the next guest lecturer: Kris Krouse, executive director of the Shirley Heinze Land Trust.

He’s worked there since 2005. When someone first told him about the job, he had two questions: Who’s Shirley Heinze? And what’s a land trust?

Shirley Heinze, Krouse explains, lived in Ogden Dunes and died in 1978, when she was in her early fifties. With $30,000 (about $106,600 today) her friends established the land trust in her name. The trust now owns 3,400 acres across six counties. The goal is to permanently preserve these natural lands, protecting them from development.

Krouse wears a blue plaid shirt and a baseball cap with the trust’s logo on it. During his part of the tour, he shows the group two of the trust’s parcels. The first is along the East Branch of the Little Calumet River, which flows to the National Park. The corridor is unique, Krouse explains, because “it’s still intact in a lot of ways”—it hasn’t been entirely ditched or otherwise altered. It’s home to more than 700 species of plants. And there are now three kayak launches along the corridor, so visitors can see it all up close.

“Blue-gray gnatcatcher,” Bouman interrupts. He’s looking at the Merlin app, which identifies bird calls. There’s also “a hawk in here somewhere.”

Krouse grew up in Indiana, and like Labovitz, he has to strike a balance with industry: “You can’t get one or two degrees away from your immediate family without knowing somebody that works at a steel mill.”

At the same time, there’s increasing pressure on industry to think about ecosystems. “We had a big fish kill. I’m sure Paul mentioned it,” he says. “That’s the same river we’re putting people on to go kayaking.”

The second stop: a parcel of land that’s perfectly flat and obviously “an old field,” Bouman points out. It’s adjacent to the Heron Rookery, “a disjunct part of the National Park,” Krouse explains. “Birds love it.”

Ironically, the previous owner of this farm founded Stop Taking Our Property (STOP), a local organization that opposed the National Park, which “created a lot of animosity,” Bouman says. But a land trust doesn’t take properties by eminent domain. It buys them from willing sellers and pays fair market value, Bouman explains.

Back on the bus, the group is headed to its final stop, the town of Beverly Shores. After the 1933 Century of Progress fair, a group of model houses was brought there by barge and installed along the shoreline.

Krouse stands at the front of the bus, explaining about the trust’s new nature preserve in Gary: “a globally rare dune and swale habitat on the west side,” not far from the city’s public high school. His shirt has short sleeves, and he seems distracted by something on his right forearm.

“Okay, so this is a—shifting gears for a second,” he says, pinching at something with his fingers. “This is a tick.”

“Oh my god,” exclaims Landau.

“I’m going to pass it around so everybody knows what it looks like,” Krouse quips. “No, I’m dead serious about this.” He explains the importance of checking yourself for ticks, estimating that he gets 50 ticks or so a season, but he has never been ill with Lyme disease.

After hours of appreciating nature—while hearing about the unrelenting industrial threats to it—the students seem unfazed by this legitimately scary natural threat.

Once again, it’s a case of learning to coexist.

Studying the Calumet

The Calumet Quarter—a collaboration between the Chicago Studies program and the Committee on Environment, Geography, and Urbanization (CEGU)—is offered every other year and consists of three courses, which vary. Studentsin the Spring 2024 program, called The Power of Place, took these courses.

Planning for Land and Life in the Calumet

Instructor: Mark Bouman, Field Museum; former geography professor at Chicago State University

Objects, Place, and Power

Instructor: Jessica Landau, assistant instructional professor, CEGU

Environmental Transitions and Unnatural Histories

Instructor: Mary Beth Pudup, instructional professor, CEGU

As a final project for the program, students designed their own field trip to Big Marsh Park, a former industrial site on the southeast side.