During a field trip to Indiana Dunes National Park, students in the Calumet Quarter program hiked the Succession Trail, a real-life demonstration of the concept of ecological succession. The stairs prevent hikers from damaging fragile habitats. (Photo courtesy Mary Beth Pudup)

The Calumet Region is complicated. The Core had questions.

The Calumet Region can be difficult to wrap your head around.

The Calumet—the name means “pipe” in French, a reference to the ceremonial pipes used by Native Americans—starts less than ten miles south of Hyde Park. There are important natural areas in the Calumet, including the Indiana Dunes National Park and the Indiana Dunes State Park. There is lots of heavy industry, most notably steel mills. And there is plenty of residential property, from ordinary ranch-style houses to million-dollar lakefront homes. All of this is mixed together in a confusing hodgepodge of land use.

The students in the Calumet Quarter program had a program of three nine-week courses to help them assimilate the complexity of it all. Meanwhile the Core sat in on a few meetings of one course and tagged along on one field trip. So many questions remained.

The three instructors for the Spring 2024 program were kind enough to answer some of these questions, starting with what would seem to be a simple one: Where is the Calumet?

The answer—like everything to do with the Calumet—was not simple.

Interviews have been edited and condensed.

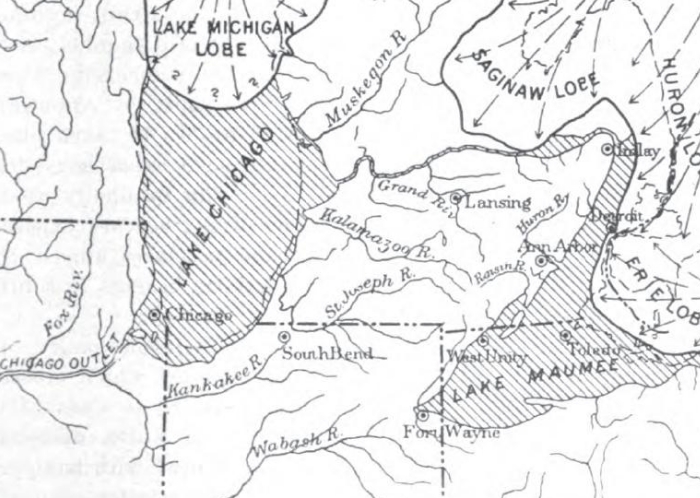

Where is the Calumet Region? Is it where Lake Chicago—a prehistoric lake that is the ancestor of Lake Michigan—once was?

Mark Bouman, senior environmental social scientist at the Field Museum and former geography professor at Chicago State University: That’s pretty close. You could define it as glacial Lake Chicago—but the rest of the city of Chicago is also part of that.

One question is, how far north do you draw a boundary? Some would say it begins at 79th Street, which is where the steel mills began. Some would have it a little further south.

You could define it as the watershed. The Little Calumet and the Grand Calumet rivers both start in Indiana and flow west. Little Cal starts just outside Michigan City, Indiana, and flows all the way over to Blue Island, Illinois, before it does a hairpin turn and comes back, meets the Grand Calumet, and flows into Lake Michigan in South Chicago. That’s the historic watershed, but like the Chicago River, it’s been played with. It’s connected by canal to the Mississippi River system. The actual drainage divide has been moved. So now the Continental Divide is at the O’Brien Lock and Dam at 130th Street.

You could define it as the industrial landscape—the steel mills and so forth. That does imprint a really strong character. On the other hand, the rest of Chicago is also very industrial.

And then you could define it by what people call it. Geographers use the term “vernacular region.” You look at place names: business names, street names, township names. In Valpo [Valparaiso, Indiana], there’s a Calumet Street. There’s Calumet Township in Lake County, Indiana. There’s Calumet Park, Illinois, a suburb over by Blue Island. Calumet High School, a little north of that. In Northwest Indiana, they call themselves “Region rats.”

It’s grounds for endless argument. In the center of it, when all those traits hold strongly, you know you’re in it. But it’s hard to know where the actual boundary is.

What’s your favorite part of the Region?

Mary Beth Pudup, instructional professor in the Committee on Environment, Geography and Urbanization (CEGU): I’m from Pittsburgh originally, so probably Gary [Indiana]. I just connect with it. I could relate to those working-class neighborhoods more than the Dunes, even though they are gorgeous. When you’re at the Dunes, if you kind of put blinders on—particularly for the mills to the west—it’s hard to believe you’re not in California.

How did you get interested in the Calumet?

Mark Bouman: Forty years ago, I was an undergrad at Valparaiso University [in Valparaiso, Indiana], at the southeastern end of the region. I took a geomorphology class, and we did a field trip looking at the impact of glaciers on the Region. The Calumet is a classic postglacial landscape.

I thought I wanted to be a historian. I realized I was interested in the history of the landscape itself.

Mary Beth Pudup: I went to graduate school at UC Berkeley. While I was there, I contributed a chapter to a book edited by the geographer Robert Lewis [Manufacturing Suburbs: Building Work and Home on the Metropolitan Fringe (Temple University Press, 2004)]. I wrote about the Calumet industrial district.

The Chicago School of Sociology model of urban development is that everything grows out from the center. I argued that the Calumet was settled and established before the ring reached it, and that Chicago developed in a polyglot way.

Jessica Landau, assistant instructional professor in CEGU: I am trained as an art historian, but most of my recent research and teaching has been in the environmental humanities. I’m interested in the late 19th– and early 20th–century origins of conservation legislation, which have left a lingering legacy in our current policy.

In the environmental humanities, we’re not just thinking about pressing environmental issues going forward, but the history—how we got to where we are. I also have a background in museum studies.

Connected with that, you had students prepare object reports for your course, Objects, Place, and Power. What did that involve?

Jessica Landau: That was the main project in my course—two object reports. I assigned each student objects in the collections of the Blue Island Historical Society and the Cedar Lake Historical Association [Cedar Lake, Indiana], giving very little context, only a general title: lantern, corn sheller.

At first the students thought they weren’t going to be able to learn anything. I think they were shocked by the depth and breadth of information they found—not just local history, but regional and national history, and in some cases, international history.

For example, one student wrote about a violin stringing machine from the Cedar Lake Historical Association, and the international commerce between the United States and Italy related to the production of classical instruments.

I think it was surprising to realize how much information objects can hold, even objects that seem mundane.

What do you think the students in the Calumet Quarter program found most surprising?

Mark Bouman: When we had an overnight field trip at the Dunes, we did a hike, and for some of the students, that was their first hike ever. We did it at night, in the rain. There was a lot of exhilaration about it.

We had some really tactile experiences on the field trips. We did a walking tour of downtown Gary where we went into an abandoned church. We went to the bottom of the Deep Tunnel shaft, 350 feet below, the lowest point in the city of Chicago where you can stand.

At the National Park, they thought there would be a big reveal, like Yosemite, and then … there isn’t. There are houses right next to it in Ogden Dunes, so on the dune hike in the National Park, we saw invasive shrubs introduced by homeowners just a few hundred yards away. I think that was a surprise, that you can have a national park with tremendous species richness. But the story is about the tenacity of those species, as much as the breathtaking grandeur of the landscape.

Mary Beth Pudup: I think just the brute materiality of history surprised them. For the last class meeting, I had the ecologist Alison Anastasio come in. She used to teach in the Calumet program.

Alison has been working with a team on the ecological change in brownfield sites, or wastescapes. She has this notion of novel ecologies. Her view is we’re never going to get rid of the slag there [a byproduct of steel production]—because where are you going to put it?

So rather than seeing it as a barren hellscape, well, what is it? What’s growing there? It’s a new thing to consider these wastescapes not as places to remediate, or places that you cap and ignore.

Jessica Landau: I think a lot of the students thought that this program was going to be about industry and environmental injustice. I think they were surprised to find resiliency and beauty.

University of Chicago students are hungry for nuance, but they also have a hunger for criticism. Being at the Indiana Dunes was beautiful and amazing. I don’t think they were expecting to find it spectacular there.