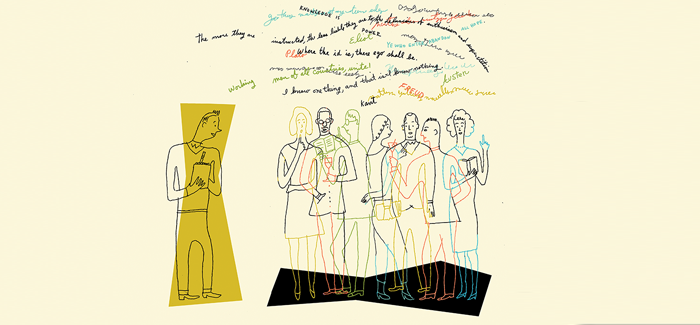

(Illustration by Marc Rosen)

An alumnus remembers—and misremembers—his Aims of Education address.

I glory in the fact that, built into the word aim is “confusion,” disagreement, and argument. Therefore, I propose to take as my revised title for this evening’s address, “A Guess about Education.”—Jonathan Z. Smith, The Aims of Education, September 25, 1982

It was the most miserable week of my life. Maybe in some novel somewhere the first week away from home is a grand liberation, a sparkling opening up into the possibilities of the world. But for me, that sweltering week in September 1982, it was different: dust, sweat, the worst case of acne in my life, fear, spurts of terror, realizing my identity was as substantial as jelly, and sleeplessness. How many things could go wrong? Luggage in tow, anxiety in abundance, I disembarked at the first gothic-looking stone structure the airport shuttle stopped at, only to realize as it pulled away that I was at International House, not my dormitory, located half a mile away.

Unwilling to betray my stupidity, I dragged my suitcase and typewriter across the sun-stoked Midway Plaisance, arriving at my dormitory, near tears, a soggy mess of a human being. An upperclassman helped bring my baggage up three flights of stairs. At the end of a narrow, dark hallway, across from the only men’s room on the floor, I opened the wooden door—bed, desk, window, closet. A small square cell.

At night I lay in bed, mind spinning with worry about math and German placement exams, and listened to a never-ending tide of visits to the bathroom: streams of piss (loud, soft, hissing, splashing, the sputtering stop-and-start varieties), the flush of the toilet, joking and laughing, and endless shower rituals. In a closet with a glass door and a hard wood seat in the middle of the hallway was one telephone—my only link to the outside world. But that week it was almost always occupied by upperclassmen who were on campus early for athletic teams. They called their girlfriends. I called my mother.

Courses in the range of the liberal arts were designed to impart a certain savoir-faire.

When would this calamity of growing up be over? At the end of this longest week of placement tests and rides on public transportation and city tours and meals in the high-ceilinged, wood-paneled dining hall, there was the first important lecture. It was held in Rockefeller Chapel. The mammoth, medieval-looking edifice was lit up against the night sky.

The title of the event, The Aims of Education, was a nod to philosopher Alfred North Whitehead, who delivered the first such address in England in 1912. Surrounded by hundreds of freshmen, desperately trying to track the meandering discourse, my attention perked up when our speaker, Robert O. Anderson Distinguished Service Professor of the Humanities Jonathan Z. Smith—big glasses, a wizard’s beard, bushy hair electrified with intelligence—shared a mischievous bit of wisdom.

We would never have to dread meeting people at parties, he opined, because a well-rounded education would equip us to make conversation with anyone. That’s it? At 18, I had never actually attended a cocktail party. I had not yet had my first alcoholic drink. I was the first person in my family to attend college. My parents and grandparents had scrimped to cover expenses for an education that would make me a smart-talking bon vivant? Really? At times like these I had the uncanny ability to channel the voice of my maternal grandmother—a tone equal parts judgment and exasperation—who survived the Great Depression with stories of hardships survived and the goodwill of unspoken heroes. Oh, you’ve got to be kidding me!

The world is not “given.” It is not simply “there.” We constitute it by acts of interpretation. We constitute it by speech, and by memory, and by judgment. It is by an act of human will, through projects of language and history, through words and memory, that we fabricate the world and ourselves.

Thirty years after that unnerving pronouncement, I was at a summer party in my hometown of Portland, Oregon, with some colleagues, and their friends, and many people I didn’t know. As the evening wore on, I circulated through the garden and asked guests about books they were reading, their take on the latest government quandary, or the kind of work they did.

After chatting with an accountant who was passionate about The Lord of the Rings—one of the more challenging types with whom I might find common ground—I had this self-congratulatory flash: I’m not half bad at this cocktail party thing. This led to a realization: Professor Smith was right. I get it now. It really is all about the cocktail parties. The truth of his provocation, I realized, had lurked in the background of every endeavor. As a consultant and teacher and neighbor and citizen, I had often needed to work with people with different interests, often widely divergent from my own, sometimes things I wasn’t interested in at all. T

o be successful and effective, one had to be connected, not just professionally, functionally, but personally. The cocktail party was a microcosm. The skill to navigate them—to have an expanded curiosity, to find what was interesting in any random person, to discourse—was an indispensable talent at the root of civic connection. After six years of education at the University of Chicago, I would eventually forget many things—the German language, for example—but I never forgot that professor’s idiosyncratic observation. Why had his words about the cocktail party imprinted me? I had to get my hands on his Aims of Education, to read it again, to find out why.

But, there is a double sense to the word fabrication. It means both “to build” and “to lie.” Education comes to life at the moment of tension generated by this duality.

Finding this old lecture was not easy. The University website where past addresses are kept includes nothing before 1991. Professor Smith, now emeritus, is unreachable, famously opposed to all technology. (A Chicago Maroon feature warns that as of June 2, 2008, Smith had never used a computer. He continued to type or handwrite all of his papers. Furthermore, he said he despises the telephone and thinks “the cell phone is an absolute abomination.”)

When I called his University extension—perhaps I’d be lucky?—I heard something I haven’t heard in years: a phone ringing without terminus in any kind of voice mail. An administrative person suggested I leave a handwritten note under his office door and wait six months for a reply. I became obsessed. I wanted the exact words. I called the librarian charged with keeping University archives. She couldn’t find the lecture but found a reference to it in a 2010 issue of the Maroon, which suggested that it had been published there in 1982. She told me to contact the folks in microforms, who advised me that the only people who had access to microforms were those who showed up in person. But I’m in Oregon! I complained.

My obsession ballooned in proportion to the impossibility of getting my hands on the damn lecture. I called friends in Chicago to see if someone would head over to Regenstein Library. Exasperated, prepared to offer a bribe or to argue, I called microforms again. This time it was a different librarian. He explained the same rule, then asked in a quizzical tone, “So, what’s so interesting about this lecture?” “It’s about cocktail parties,” I blurted. “He said that the aim of a rigorous liberal arts education is to help you navigate cocktail parties more suavely.” “Well,” he said, “That is interesting,” and offered to photocopy the lecture and mail it to me.

What is required at this point of tension is the trained capacity for judgment, for appreciating and criticizing the relative adequacy and insufficiency of any proposal of language and of memory.

When the precious envelope from Regenstein Library arrived, I ripped it open and pored over Professor Smith’s Aims of Education. The address was 16 pages, over 4,500 words long. I was swept back into that freshman despair of trying to track the essaying of a great mind over a bedeviling question: What is the purpose of a liberal arts education? Heart sinking, I reread the lecture multiple times before I had to admit a new truth: He never said anything about cocktail parties. I had lived my life according to a lie. How could I have conjured such a dramatic misunderstanding?

For argument is not based on the world as it is, but rather on what the world might imply. It is the world refracted—no longer the world, but rather our world—a world of significance, interpretation, and, therefore, of argument.

That night of the Aims of Education, I was fatigued. I kept wondering whether my acne was worse than the student’s sitting beside me. I was calculating how I might watch the next episode of M*A*S*H. I was wondering if I could petition out of my dormitory, citing emotional distress caused by the noisy lavatory. In his actual address Professor Smith recalls ideas of liberal education from past eras, experiences “designed to impart a certain savoir faire, a broad civil, cultural, and civic veneer.” He mentions “a genteel space” and liberal learning as “the acquisition of the civilized art of gossip,” words and images that sound a bit like cocktail parties.

I suppose in the moment he could have riffed on the cocktail party idea, but no other classmate, contacted decades later, could corroborate it. That night and the next few days after the address, I would have participated in conversations about this talk. Someone else might have said something about cocktail parties. My memory of that night is layered with experiences that followed when I participated in a venerable institution: Friday afternoon sherry hour. Students and professors mingled in a wainscoted lounge, making introductions, sipping drinks, listening to the grand piano, talking about books and events of the day.

At Brent House, the Episcopal chaplaincy at the University, where I lived for three years, it meant learning the proper way to brew tea, nibbling cookies, and making guests feel welcome. Over time these up-close-and-friendly occasions leveled the hierarchy. The hard edges of the world softened, opened up. I came to appreciate the art of conversation, the uses of friendliness, the importance of human connection, and the generosity of mentors.

Still, I had fabricated a startling piece of mischief that had never occurred. I had held onto it for the better part of a lifetime. But perhaps I can be more generous toward that teenage boy who was musing about cocktail parties when he should have been tracking the professor’s words. Perhaps he was merely interpreting. Perhaps he had a premonition of those Friday gatherings, or over time memories of sherry hours mingled in his mind with the address. Perhaps he was mediating what the professor said through the lens of his own unspoken longings: an urbane setting where people are interested in him and he can express his curiosity to know who they are; a place where, in spite of the vast unknown that stretched before him that evening in the chapel, he would eventually, to his surprise, belong.

Wayne Scott, AB’86, AM’89, is a writer and teacher in Portland, Oregon. This essay is dedicated to Gretchen Holmes, AM’10, and Raymond Gadke, AM’66, both of whom went beyond the call of duty to track down the elusive address.