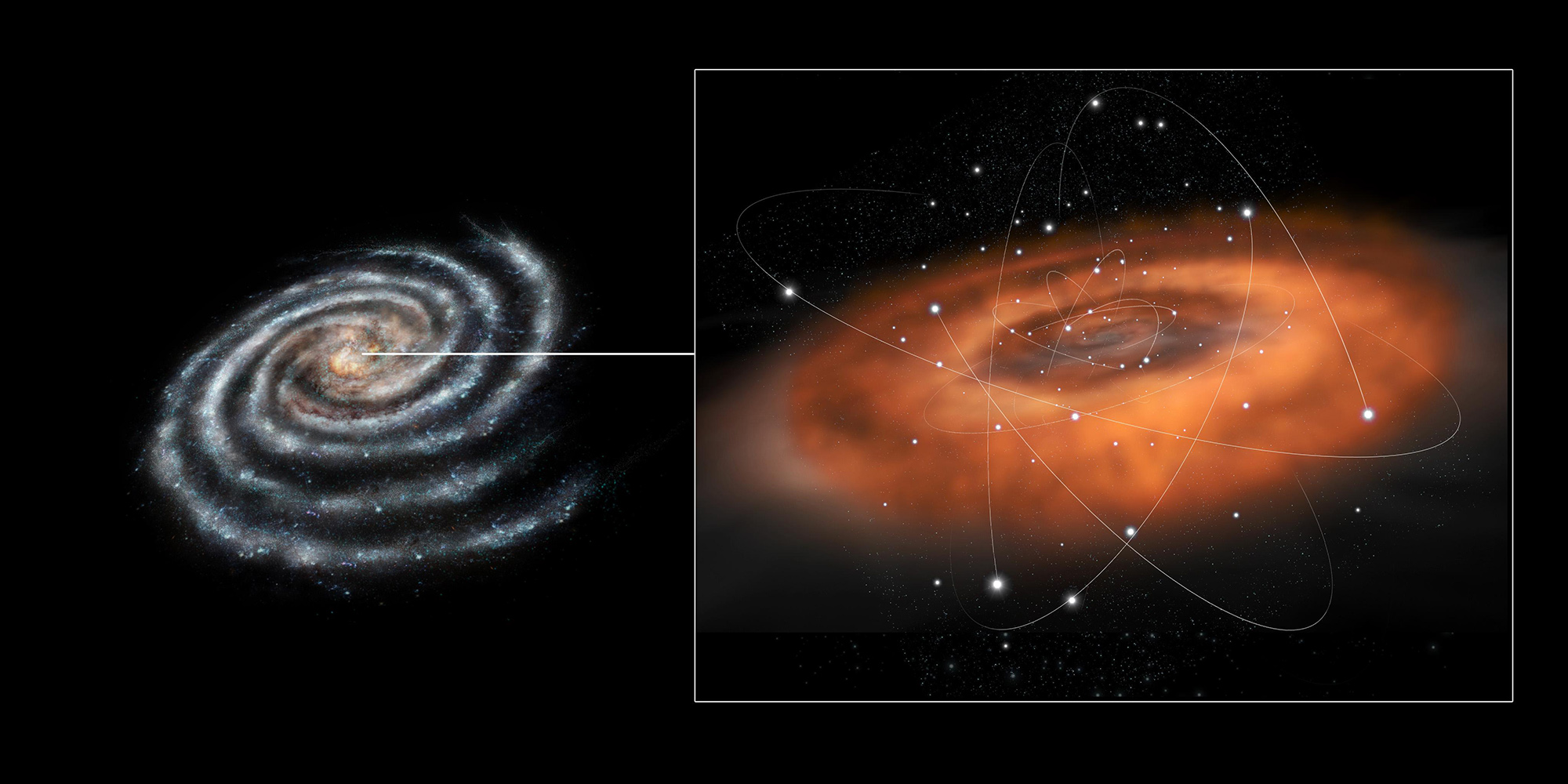

This conceptual illustration shows the activity at the center of the Milky Way galaxy where the supermassive black hole Sagittarius A* resides. (ESA/C. Carreau)

Supermassive black holes, optimal oxygenation, and rising health care costs.

Star scraps

Casual stargazers can’t see Sagittarius A*, the supermassive black hole more than 26,000 light-years away at our galaxy’s center, devouring matter around itself. Data taken from various telescopes, including NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory, are necessary to capture it. Astrophysics PhD student Scott Mackey, SM’23, and collaborators used the observatory’s archive for a study published May 9 in the Astrophysical Journal Letters, investigating the role of black holes in galaxy formation. By collating 13 X-ray images from 2005 and 2008, the researchers identified an “exhaust vent” atop a known chimney of gas streaming hundreds of light-years away from the galactic center. Thought to be the waste disposal for the scraps Sagittarius A* spits out, the vent system may help researchers discern how often the black hole consumes and excretes cosmic material. It might also explain how the mysterious galaxy-sized Fermi and eROSITA bubbles around Sagittarius A* came to be.—R. M.

Breathe easy

Each year millions of critically ill patients worldwide require mechanical ventilators to help them breathe. While doctors aim to keep these patients’ peripheral oxygenation-saturation (SpO₂) levels—the amount of oxygen in their blood—between 88 and 100 percent, the specific target within this range was thought to be inconsequential. But a study led by UChicago Medicine pulmonary and critical care fellow Kevin Buell, SM’24, indicates that optimal SpO₂ levels do exist—they’re just different for each individual. In the study, published March 19 in the Journal of the American Medical Association, researchers used a machine learning model trained on randomized trial data to predict the ideal SpO₂ level for critically ill adults on ventilators. They found that optimal blood oxygen concentrations could potentially be determined using specific demographic and health data, such as age and heart rate, and that for patients whose SpO₂ levels fell within the algorithm’s ideal predicted range, mortality would have decreased by 6.4 percent overall. If implemented in clinical settings, these findings could lead to more personalized care and higher survival rates for the critically ill.—S. M.

Costly effects

Since 2000 prices in health care have risen faster than those in any other economic sector in the United States. Because most Americans receive health insurance through their or a family member’s job, those rising costs are not directly borne by consumers but are passed on to employers. So how are employers reacting to the upticks, and what are the broader economic effects? A June 2024 working paper led by Zarek Brot-Goldberg of Harris Public Policy answers those questions using data from hospital mergers, which have been shown to increase health care costs. Brot-Goldberg and his colleagues compared non–health care employers that were heavily exposed to hospital mergers with those that were less heavily exposed. The results painted a bleak picture: for every 1 percent that health care costs went up, employers reduced employee head count by 0.4 percent and payroll by 0.37 percent. That translates to a 2.5 percent increase in unemployment insurance payouts—demonstrating that rising health care costs significantly affect federal and state budgets as well as employers and workers.—S. A.