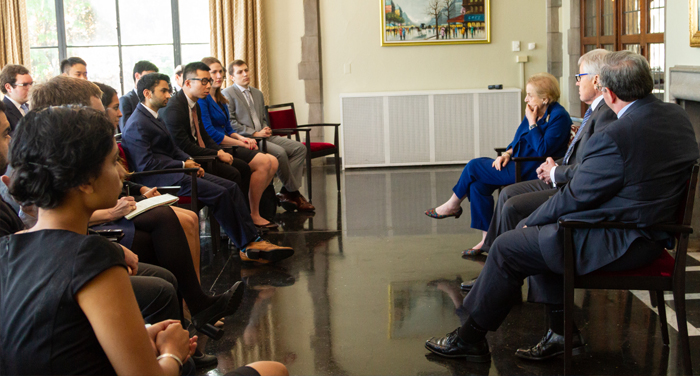

At the Quadrangle Club, undergraduate and graduate students had an hour to question Madeleine Albright and Chuck Hagel. (Photography by Jason Jones)

The first annual Hagel Lecture at UChicago brought together Madeleine Albright and Chuck Hagel to speak to students and the public.

“The world’s a mess,” said Madeleine Albright. On this evening late in May, more than 900 people had filled Mandel Hall to hear the former secretary of state and Chuck Hagel talk foreign policy and world politics in the first annual Hagel Lecture, named for the former secretary of defense and Republican senator from Nebraska.

The lecture was hosted by the Chicago Project on Security and Threats (CPOST). Introducing the two political heavyweights (who are also good friends) was CPOST’s founder and director, Robert Pape, PhD’88. In his remarks, the UChicago political science professor also provided a brief introduction to CPOST, a nonpartisan center that “generates authoritative, advanced knowledge to improve security and prosperity in practical ways.” Gathering and analyzing masses of data, CPOST’s teams of faculty and students aim to answer questions critical to international politics, security, and trade.

The project’s origins trace back to Pape’s Suicide Attack Database, begun after 9/11 as a comprehensive record of attacks and attackers. Regularly updated, it remains an essential tool for scholars and government and is one of many ongoing projects based at CPOST today. Among them is Pape’s current collaboration with psychology professor Jean Decety to study online terrorist propaganda and recruitment.

Another project, led by CPOST associate director Paul Staniland, AB’04, associate professor of political science, asks why terrorist groups in South Asia sometimes work against and sometimes in concert with the region’s governments. To answer that question, Staniland’s team is building a database cataloging all instances of and changes in state-insurgent relations in the region since 1945.

Benjamin Lessing, also a political science associate professor and CPOST associate director, studies organized armed violence by gangs and drug cartels in Latin America. The database Lessing’s team is at work on will help them estimate how many people are effectively under criminal governance, including by criminal gangs operating from inside prisons.

Data is one sine qua non of CPOST’s work. The other essential, says Pape, is “building real bridges and connections.” That means making CPOST’s data accessible to other scholars and establishing connections to Washington. Reaching out to the broader public is a priority too, and is where the Hagel Lecture comes in.

The relationship with the former defense secretary, and others like it, are indispensable to what Pape and CPOST want to achieve. As Albright told the Magazine, a pipeline from the academy to the policy world is “exactly what needs to be happening in terms of putting the intellectual rigor into getting data, and then making it available to government decision makers. … This is a remarkable exercise and very, very useful.” On the other side, Hagel added, “it gives our academic friends some balance and perspective on how policy is made.”

At Mandel Hall, Albright kicked off the evening with brief remarks before Pape moderated a conversation between her and Hagel. Pape then invited students in the audience to ask questions about global problems and policies. How to better the messy, dangerous, and endangered world of Albright’s opening comment? The two drew on their own experiences at the highest levels of government to advocate for bipartisanship, diplomacy, and the deep engagement of young people like the evening’s questioners. View the entire program.

That wasn’t the only chance for UChicago students to ask questions that day. A few hours earlier, across University Avenue, two dozen or so graduate students and undergraduates who work with CPOST gathered in the bright, intimate setting of the Quadrangle Club’s second-floor solarium. Exuberant yet businesslike in suits and dresses, they chatted about final exams and papers as they waited for Albright and Hagel to arrive. Following a group photograph, the duo settled in to take questions.

The following extracts from this session have been edited and condensed.

What is your advice for those of us in the younger generation who want to be future policy makers, who may be slightly naive currently but at the same time want to make a better future?

Madeleine Albright If you are going to enter public service, you have to know your value system and try to figure out how you are going to make your views known. I have students [at Georgetown University, where Albright is a professor of diplomacy] now who are coming to me and saying, “Do you think we should go into this government? We disagree with what they’re doing.” And I say, yes, you should, because there need to be people there who are interested in foreign policy, national security policy, and all the elements of it.

I hate to say this to you, but I say to my students that when they first go in, they are not going to be making policy, they’re going to be stamping visas. There’s value in being in the system and learning how it works, and then, as you rise up in it, having the opportunity to state your views clearly and show why you believe in them.

I don’t think people should forget what they believe in. National security policy has to be based on values and ideas. What any system needs is to have people with different ideas who are figuring it out— not always saluting and saying, I’m going to do everything that I’m told to do.

Chuck Hagel You always have to remember that our country, our Constitution, our institutions, are much, much bigger than any one individual. We’re all just fleeting stewards of the same.

There will be another president, and then another president. Your loyalty is to the country. We all take an oath of office when we enter government. It’s to the Constitution. It’s to our country, it’s to people, America. We don’t take an oath of office stating loyalty to a president, to a political party, or to a philosophy.

If you believe you can make a contribution to our country to make it better, that’s where it starts. That’s the fundamental anchor, and then you go from there. I’m often asked, as Madeleine is, by a lot of young people, should I go into politics, should I run for office? And I say, that’s your decision. I can’t tell you if you should do it or not do it. But I would give you this advice, and I think it applies to all things: you’ve got to ask yourself some pretty fundamental questions that only you can answer. The most fundamental is, why do you want to do it? If the answer is not to make a better world, then I tell them, don’t do it. That should be the answer down deep in you.

Is there anything in your tenure that, if you had a chance, you would do differently?

Albright I second-guess myself about everything. I am often asked if we did the right thing in Kosovo, for instance, or did we do the right thing in expanding NATO. I think it is worth thinking about, and what would have happened if you didn’t do it. Would it have made a difference? In those particular cases I think I came out on the right thing.

The one that I find the hardest to deal with happened when I was ambassador at the United Nations, over Rwanda. We did not go in with a peacekeeping operation in Rwanda. I can explain why we didn’t. I won’t take the time to do it, but it made a lot of sense at the time. But given what happened, I think it would have made a big difference to go in.

Usually you’re not the only person making the decision, especially a big one. It comes as a result of a principals meeting or an interagency meeting of some kind. Then the question is more like, should I resign over that? You do go over things, there’s no question. If you don’t, then you shouldn’t have the job. It’s worth analyzing why you did it, especially if it doesn’t have a happy ending or it’s a difficult issue. Asking yourself about do-overs is an essential part of a decision-making process.

Hagel I agree with everything Secretary Albright said. You can second-guess yourself into paralysis, and you can talk yourself into anything. Now, you should always be second-guessing yourself—not to paralysis, but you’ve got to come at it from all the different perspectives: Is this the right thing? Why isn’t it? Go back and review it. That’s part of a process that I’ve tried to maintain in every job I’ve had. Take inventory. If you’re doing that honestly with yourself, then you’ll come to the right decision on almost everything. There are situations where I could have done something better, I should have said it differently, I should have said it better, maybe made a better decision. But you build on those experiences and learn from them, and hopefully you get better.

How does cooperation between the State Department and the Department of Defense play out, and how can diplomatic solutions still play into an evolving security situation when you do need stronger military forces on the ground, as in Syria?

Albright In a course I teach called The National Security Toolbox, I say foreign policy is just trying to get somebody to do what you want. That’s all it is. So what are the tools? We are the most powerful country in the world, but there are not a lot of tools in the toolbox. There’s diplomacy, bilateral and multilateral; economic tools of aid and trade and sanctions; the threat of the use of force; the use of force; intelligence; and law enforcement. That’s it.

The reason I started teaching the course is that I remember what it was like in the Carter administration when the Soviets invaded Afghanistan. We had an interagency meeting and it was insane. We knew we couldn’t get the Soviets out, but we were trying to figure out how to punish them. So it was like show-and-tell, saying, well, we can cut off their fishing rights or we’ll have a grain embargo or we’ll have a call-up of the draft. Ultimately somebody said, we’re not sending our athletes to the Olympics. I thought, this is the most disorganized way of trying to figure out how to do this.

The toolbox is what’s discussed in these meetings. Diplomacy is the bread-and-butter of things, but it’s viewed as weak. Sometimes force is used at the end, because it’s strong. And an awful lot of times you use economic tools. But the discussion is often ultimately about the relationship between state and defense.

I’ll never forget this: I was outside the Situation Room standing with General [John] Shalikashvili, who was chairman of the Joint Chiefs at the time, and [Robert] Rubin, secretary of the treasury, walked by and he said, “Aha: force and diplomacy.” Shali said, “And which is which?” Because I was more inclined to use force, and he was inclined to use diplomacy. I do often think that the State Department is more prepared to use force than the Defense Department.

Hagel In almost every case the military should be used only if there’s a diplomatic agenda. Now, if America is attacked, that’s different. But when you use your military, you want to use it with as much precision as you can. It should follow the ultimate objective, and that’s got to be led by the State Department, in conjunction with the White House and the president. Ultimately, where does the president want to go with this? What does the president want to accomplish?

The relationship between a secretary of state and secretary of defense is important to make it all work. When I was secretary of defense, [Secretary of State John] Kerry and I would meet once a week. That was very helpful. We could clear our own thinking with each other, and then we would meet when everybody was in town once a week with the national security adviser. The interests of all three don’t always come together, but Kerry and I had a relationship where he never surprised me, I never surprised him, and that was really important.

What are the current challenges of dealing with the Middle East, especially in situations where national security interests dictate what the United States does?

Albright I think we don’t fully understand all of the complications of the Middle East. In addition to artificial countries having been created, most Americans don’t know much about Islam, much less the difference between Shia and Sunni. And they don’t focus on the centuries-old struggle between Arabs and Persians and that complicated aspect of it.

The issue is always whether American foreign policy is idealistic or realistic. That’s a false dichotomy. I never could figure out if I was an idealistic

realist or a realistic idealist. You need both. And as hard as it is to say, especially to young people, our policy is inconsistent because we look at various countries and realize we need them for X.

My problem at the moment would be Saudi Arabia. They have, from everything that one can tell, committed murder on the orders of the highest echelon. On the other hand, I think it’s very important to have relations with Saudi Arabia. I personally would not sell them arms at this moment, especially with what’s going on in Yemen and the Houthi, but I think it’s crazy to break off relations.

So one makes certain allowances for having a pragmatic relationship. When I was in office, I always believed in the pragmatic, but I never gave up on human rights. No matter where I was, talking about whatever, especially in China, I would say, you know, you’ve got to do something about your human rights policy. We need to do both.

Hagel Every nation always responds in its own self-interest, and its foreign policy is conducted on that basis. At the same time, as Madeleine mentioned, there’s always a struggle between the idealism and realism in the principle of foreign policy. The principle, I’ve always thought, is a foreign policy that includes our self-interests, that has a strong defense of human rights, liberty, values, and that melds that with the reality of an imperfect world and the imperfections of what the Middle East represents: unfortunately, authoritarian governments.

As for Madeleine’s mentioning of Saudi Arabia, that’s exactly where I am too. We couldn’t walk away from that relationship, because there’s too much at risk. But there are things we can do. The Congress did pass a law not allowing funding for the Yemen war, but the president vetoed that.

The essence of diplomacy is finding smart, realistic—but yet as idealistic as we can—ways to solve problems. If you give away the idealism of your foreign policy, and if that’s seen by other countries as walking away from it, then this world is in for a real tough time.

We are seeing more and more of a drive toward authoritarianism in the world. Xi [Jinping] probably is a master, with as much power as any Chinese leader since Mao [Zedong]. Obviously [Vladimir] Putin, [Recep Tayyip] Erdoğan in Turkey. You’re looking at Western democracies in Europe, like Hungary and Poland, that are moving in those directions.

We have been the one country that more than any other has stood for values and tried to implement idealism and “let’s do this right.” Now, we’re more powerful. We’ve got more authority. Maybe you could say, well, that’s our responsibility. But it’s easy to forfeit that too.

I’ll give you one example. I was secretary of defense when the president of Egypt was overthrown in a military coup by [Abdel Fatteh el-] Sisi. I’d been in Egypt a month before that, and we met with the president and Sisi, who was defense minister at the time. I remember the National Security Council meeting with the president [after the coup]. A lot of the conversation was, let’s pull the plug on Egypt and Sisi. I was, I think, the only voice that said, we’re going to have to do something to respond to this, but let’s think this through. When you say, “pull the plug,” what do you mean? They wanted to cut off everything—everything. I remember turning to President Obama and saying, “Mr. President, if we do that, we have just lost any influence and any instrument of influence we might have left in Egypt. Plus the Suez Canal.”

As you start thinking about the consequences of that action, it’s a difficult situation always, and there are never any good options that the secretary of state has to work through. Probably the same as the secretary of defense. But I think the secretary of state has more bad options that come to him or her than anybody in the cabinet, because they wouldn’t come to her if it was good news. Figure it out, Madame Secretary.

Albright It’s still a pretty good job.

Hagel No, there are some privileges to that. So, anyway, that’s the way I’ve always seen it, and I’ve seen it up close.

With the decline and recession of diplomacy, I’m interested in the two principles of the stick and the carrot [defense and state]. How do you get those parts of our government to talk to each other and to work together in an interagency process?

ALBRIGHT Well, it’s frankly one of the hardest parts. The US government makes thousands of decisions a day. Some of them are done within an individual department, but more and more they require an interagency approach.

The hard part is, who’s the boss of the interagency process? That isn’t a problem at the top, where the national security adviser brings people together. But as you get up there, there are questions to whether the Defense Department takes the decision or the State Department. And these days it takes more and more departments. Now you have to involve commerce and treasury and health and human services.

I was a National Security Council [NSC] staffer in the Carter administration, and there’s nothing more invigorating than going into a meeting, and they know you’re the NSC and you say, “The president wants,” and then you kind of take charge of the interagency process. On the other hand, the NSC staff is basically parasitic: they depend on the other parts of the government to provide information, and so it’s, I’m in charge, but tell me what you know.

At the top, the national security adviser summons the meeting. Then it’s important to, what I would say is, break the eggs: make sure that each secretary gets a chance to speak, and with any luck to actually disagree, because I think it’s important to have different views. Then it’s up to the national security adviser to make an omelet out of it to give to the president. If you can’t make an omelet, then you give the egg mess to the president and make your arguments in front of the president.

The other part is to understand what is wrong with your argument, so that if people disagree with you within the interagency process, you can defend what you decide to do.

HAGEL The interagency process in our government reflects the reality of the interconnectedness of the world: security, intelligence, the economy, diplomacy, trade. They’re all intertwined.

I would add that it’s really important that the president of the United States set the tone as to how he wants that interagency process to work. When I was secretary of defense, it worked pretty well. The principals, the secretaries of state, defense, treasury, and others for the most part had personal relationships.

That doesn’t always have to happen, but it helps, because, as Madeleine said, it’s people that have to make it work. If you’ve got trust and confidence in each other and you’re not worried about somebody pulling something on you or not being honest, that’s really important. But the president is the one that assures that doesn’t happen.

How did you deal with disagreements with what you thought was the right choice if the president pushed back?

HAGEL When the president and I disagreed on something, my approach always was to be very straight about it, and I think the president was very straight with me. There were issues that we had differences of opinion on. You serve at the pleasure of the president. It’s clear there’s one boss. But as long as you can articulately make your case as to why you think you’re right or why whatever it is is a bad decision, that’s the best you can do. I think you owe that to a president if you think it’s the wrong direction.

Madeleine, I know, feels the same way. But all you can do is your best and give your best and most honest judgment, and then ultimately the decision is the president’s to make.

ALBRIGHT There are disagreements, and if there weren’t disagreements, we’d be living in a totalitarian society. The reason that you have this process is to hear different opinions.

And I think they’re fine so long as they are inside. One thing that frankly does happen, and you don’t know why, is somebody leaks that there was a disagreement. Or the press will call somebody and say, “I hear you quite didn’t like that discussion,” and then you think, well, I have to say I did.

Let’s take, for instance, some of the decisions on Iraq. From what one sees now, Secretary of State Colin Powell disagreed with some of the issues, but it wasn’t clear until afterward. It was not out there.

I know what President Bill Clinton would do. We would be in meetings, and he’d say, “Do you all agree? I want to hear what Madeleine has to say,” or whatever, because we were chosen for our competence in the job we were doing, and the strength we had to defend the arguments we made. One of the things that I tell my students is it’s important to know why you think something, and what is wrong with what you’re arguing. What are the counterarguments to what you’re proposing?

What are some foreign policy issues that you believe this next generation of policy makers will face?

HAGEL Our world now, and what you’re going to be facing and leading, is interconnected. Everything is interconnected. That means you’re going to have to widen your aperture more than I had to widen mine to deal with the big issues coming.

What are those big issues? Well, our demographers tell us by 2050 we’re going to have nine billion people. Just start with that. That means climate is huge. It affects everything, everybody—food production, health, security, and so on. That will be as big an issue overall as you’ll be able to deal with, because it’s everything. Obviously, the nuclear issue will unfortunately still be with us. There’s always been some form of terrorism in the world. That’s not new.

All the more reason why Madeleine’s old job, diplomacy, is going to be really critical. We’ve got to get along with people. We have to have alliances. We have to be able to rely on friends and allies. And we’ve done that pretty well since World War II.

We can’t go it alone. We’re not that good, we’re not that smart. No country can go it alone. We have to rely on other countries to allow us to base there and keep troops there. It’s in their interest as well, but certainly it’s in our interest.

All these alliances that are so critical need to be adapted and adjusted to new technologies, new opportunities, new challenges, always. That’s going to be a big part of what you’re going to be dealing with. Technology is driving this faster than anybody would have ever predicted.

And I’d say that’s the last point, managing the good—and managing the challenges and managing evil. There’s still evil in this world. I suspect there will continue to be evil, I’m sorry to say, but how do you manage that? We can’t do it alone.

ALBRIGHT I agree. I’m known as Multilateral Madeleine. The bottom line is partnerships and trying to develop those. The thing that I absolutely insist on now when I teach is to be able to put yourself into the other person’s shoes, the other country’s shoes. You can’t be involved in anything that is a zero-sum game. There is no such thing as zero-sum. It’s important to have that wider look to see what the other side needs. That is what diplomacy is about.

CPOST researchers will appear on a September 26, 2019, live broadcast of Freakonomics Radio Live! at Chicago’s Harris Theater with Stephen J. Dubner and UChicago economics professor Steven D. Levitt.