Duckworth’s Earth, Water, Sky (below) and Clouds Over Lake Michigan (above) reflect her vision of human life and the natural world: “I think of life as a unity. This unity includes mountains, mice, rocks, trees, and women and men. It is all one lump of clay.” (Ruth Duckworth, Clouds Over Lake Michigan, 1976, Ceramic. Installation view in the Joseph Regenstein Library, 2023. The University of Chicago Public Art Collection, Gift of Cboe Global Markets. Photo by Bob. Art © Estate of Ruth Duckworth.)

In Henry Hinds Laboratory and now the Regenstein Library, Ruth Duckworth’s murals make an art of geophysical science.

I say I’m a sculptor. That’s what I tell people.—Ruth Duckworth

Since 1969 Ruth Duckworth’s sculptural mural Earth, Water, Sky (1968–69) has welcomed entrants into the Henry Hinds Laboratory for Geophysical Sciences. Now, more than half a century later, the Smart Museum of Art has installed the longtime visiting artist’s massive Clouds Over Lake Michigan (1976) near the circulation desk in the Regenstein Library. It’s become a defining feature of the busiest area of the Reg.

Both pieces were inspired by the work of earth scientists at the University in the late 1960s and early 1970s. In the following pages, Laura Steward, the University’s curator of public art, traces the influence of meteorologist Tetsuya “Ted” Fujita on Clouds Over Lake Michigan, and Douglas MacAyeal, professor emeritus of geophysical sciences, explains how Earth, Water, Sky functions as a visual metaphor for a paradigm shift in the earth sciences.—Carrie Golus, AB’91, AM’93

Clouds Over Lake Michigan

By Laura Steward

When Ruth Duckworth came to the University’s Midway Studios to teach ceramics in 1964, she planned to stay for a year. Instead, she remained in Chicago until her death in 2009—nearly half her life.

Born in 1919 in Hamburg, Germany, Duckworth studied art in England, and she is still primarily known as a British studio potter, rather than an innovative Chicago sculptor. She referred to herself as a sculptor with clay. She sought to make works of timeless beauty derived from the natural world, without regard to the great art/craft divide.

At UChicago Duckworth met meteorologist Tetsuya Fujita, best known for creating the Fujita Scale to measure the force of tornadoes. Meeting Fujita transformed Duckworth’s art. His profound influence is obvious in Clouds Over Lake Michigan (1976), a massive ceramic sculpture originally commissioned by Dresdner Bank for its Chicago office.

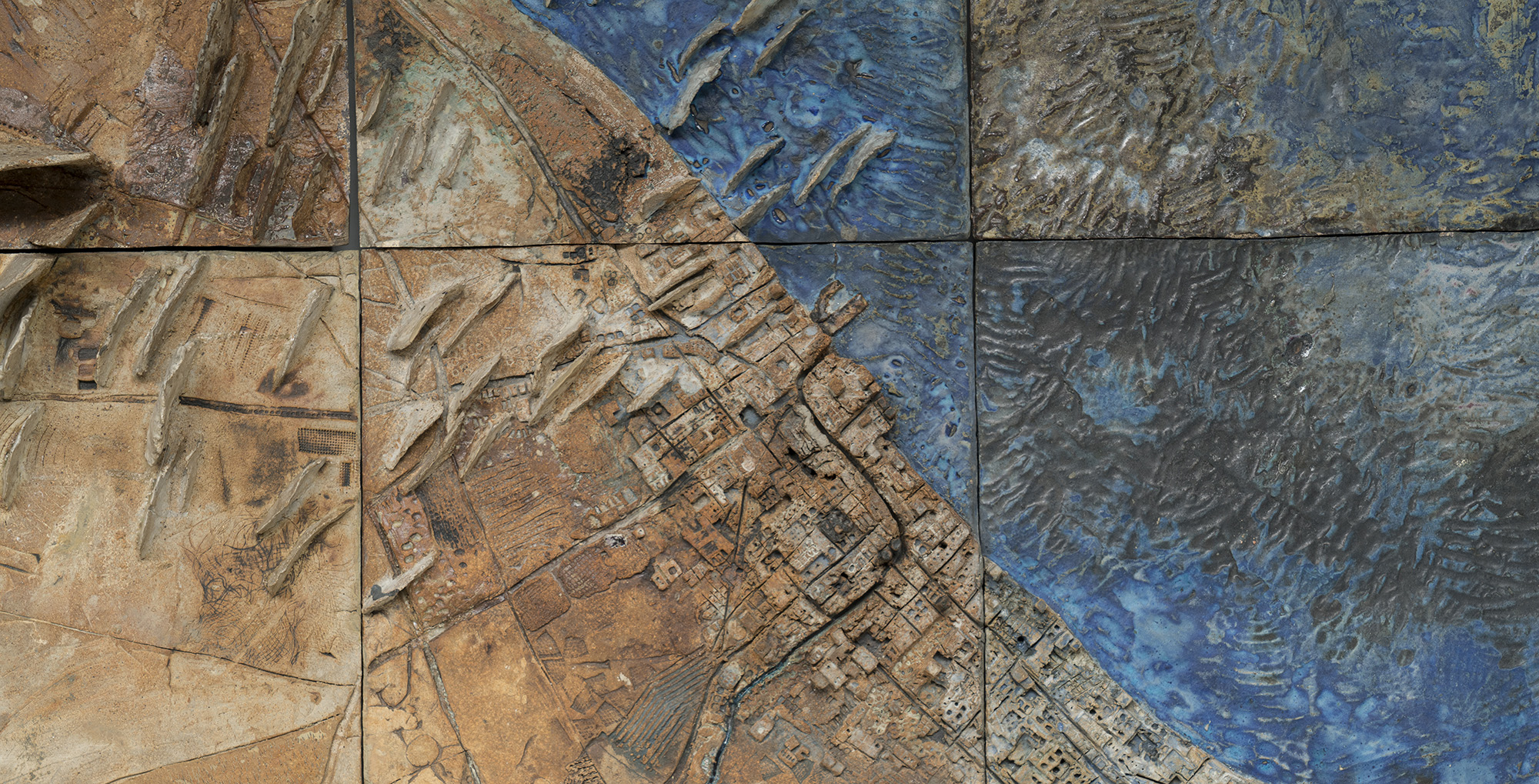

The piece, which depicts an aerial view of the southern tip of Lake Michigan and its shoreline, was installed on the first floor of the Regenstein Library this past autumn—although it looks as though it were specifically designed for the space.

Composed of 65 ceramic tiles, each roughly 22 by 22 inches, Clouds Over Lake Michigan weighs 2,500 pounds. Duckworth modeled the shapes in the work after the forms that Fujita saw in early aerial and satellite photographs of the earth. The grid pattern is another echo of satellite photography.

When the Regenstein opened in 1969, architect Walter Netsch told the Chicago Maroon that the building would not be complete until it had art installed in it.

By his definition, more than 50 years later, it’s finally complete.

Earth, Water, Sky

By Douglas MacAyeal

Ruth Duckworth captured an enduring moment in scientific discovery with her ceramic portal to the geophysical sciences department’s Henry Hinds Laboratory. At the time she was commissioned to create the work, earth science was undergoing a paradigm shift that established, for the first time, the inseparability of earth, water, and sky.

In the mid-1960s, traditional geological knowledge was turned inside out: Earth’s crust was mobile, flowing in a great pattern that split continents and opened ocean basins. The plate-tectonics revolution, as it is known now, was strongly resisted as nonsensical for decades.

With the acceptance of plate tectonics and Earth as a planet in its place in the solar system, the earth science community realized it was time to remove artificial barriers between the studies of earth, water, and sky (aka, geology and geophysics, oceanography, and atmospheric science, not to mention many other subfields of present-day earth science).

The creation of the Henry Hinds Laboratory in the mid-’60s was one visible effort toward this unification: an entryway that forced the perspective of unified earth sciences. Duckworth’s involvement was initiated by the newly formed department’s chair, mineralogist Julian Goldsmith, SB’40, PhD’47. Goldsmith’s science addressed what happens when minerals of the solid earth are exposed to water and sky: they “rust” and fall apart, leaving behind a pasty residue called clay. Clay, and the minerals Goldsmith identified that comprise it, are the materials Duckworth used to construct Earth, Water, Sky (1968–69).

While planning the artwork, Duckworth met many scientists, including Ted Fujita, a pioneer in the science of severe weather, tornadoes, and downbursts. Unlike most of his peers, he studied the atmosphere through photographs and visualizations.

Ultimately Earth, Water, Sky captured the ethos of the burgeoning “new” earth science. As scores of scientists, students, and visitors enter Hinds Laboratory daily, they are subject to a moment of visualization, where earth science is given three-dimensional form.