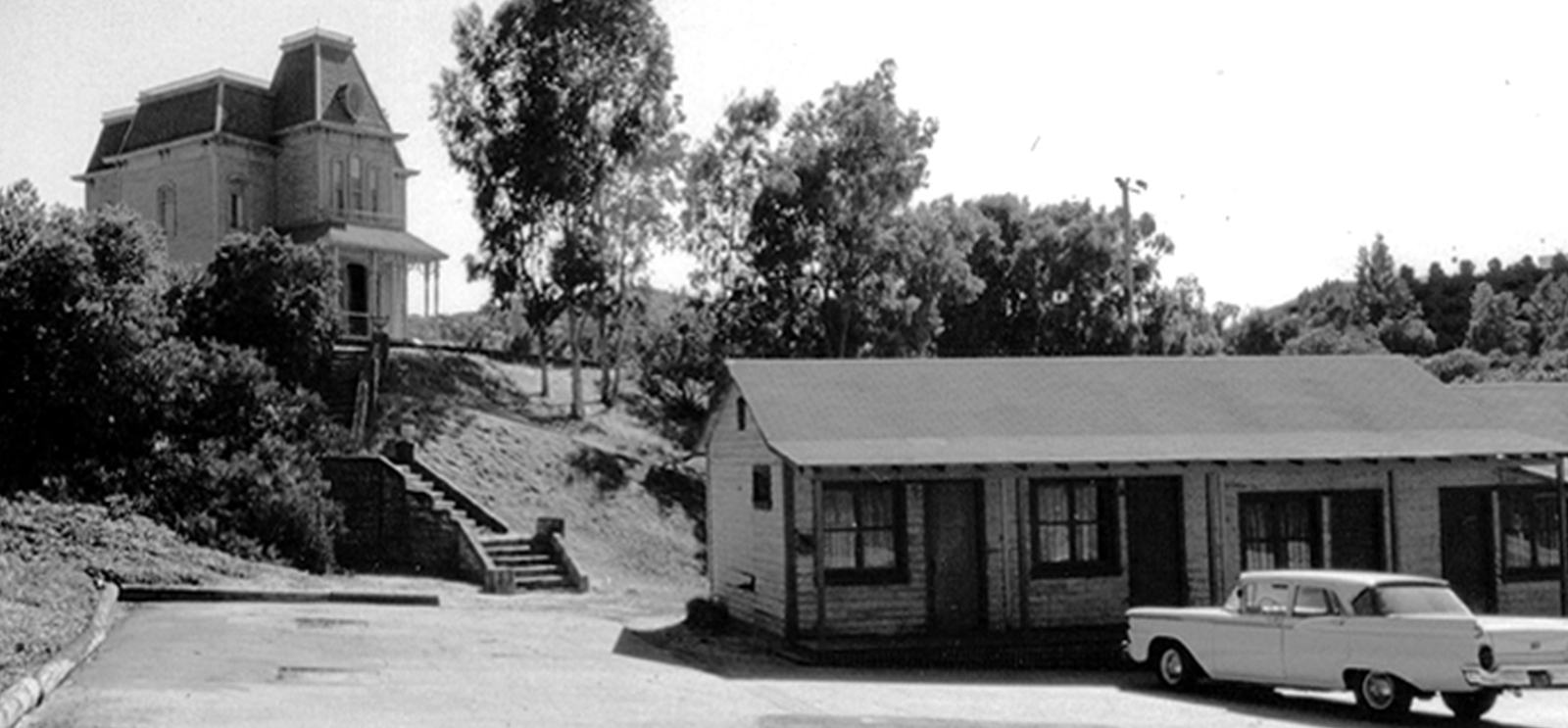

A Cinemetrics search for Psycho brings up 44 results, including a few of the famous shower scene inside the Bates Motel, shown above right. (Photo by Indu Singh)

Chicago film scholar Yuri Tsivian’s database charts movies’ tempos shot by shot.

Filmmakers have always known that shot length matters, says Chicago film scholar Yuri Tsivian, that the elapsing time between cuts helps define a film’s narrative flow and emotional texture. The camera lingers longer over a kiss than over gunfire. In an on-screen argument, the tension heightens in part because of the staccato shifts from one character’s face to another and back again. Cutaways abound during car chases, not so much during a stroll in the park.

Film scholars, too, have long understood the importance of shot lengths. Besides pinpointing a moment in the narrative, “the cutting rate”—the frequency and speed with which the shots change in a film—“says many things,” notes Tsivian, a professor in the University’s departments of art history, Slavic languages and literatures, comparative literatures, and cinema and media studies.

But scholars have had little hard data because there hasn’t been a widespread mechanism to quantify “how a film changes tempo within itself,” Tsivian says, and compare those numbers across genres, eras, cultures. He is trying to build one. In 2005 he developed Cinemetrics, an online database to which film scholars, historians, and students around the world submit shot-length data on thousands of films. Contributors download a software program and then, while watching a film, they record each cut by clicking a mouse or the spacebar when the shot changes. The software maps that mouse-click data into a graph that resembles a lopsided seismograph chart, showing the length of every shot. Trend lines show the fluctuations where a film speeds up and slows down. To date, Tsivian says, people have made nearly 9,000 submissions to Cinemetrics; some are whole films, others only specific scenes, and some are duplicates. There are five versions of My Fair Lady on the database, for example, and a search for Psycho brings up 44 results, including a few of the famous shower scene by itself. Versions may vary slightly with human error, but the longer the film, the less those differences matter, Tsivian says.

“We’re still just beginning,” Tsivian says, but the Cinemetrics data has already confirmed some scholarly hypotheses formulated in the absence of hard numbers. For instance, film historians have long held that the advent of sound in the late 1920s slowed cutting rates all over the world. In the 1910s a Hollywood trend toward assembly-line efficiency, Tsivian says, shortened shot lengths, which made films move faster. After the 1917 Russian revolution, Soviet directors—looking to prove their new country’s efficiency and modernism—borrowed the fashion for speed. For ten years, their films had the fastest cutting rates in the world. Then in the late 1920s talkies appeared. “And cutting slowed down everywhere,” Tsivian says. “To speak is a different thing than to show. To show is click-click-click. But if someone is actually speaking, the very semiotics of speech takes time.” Sound required more precise editing, which was more difficult and time consuming. “So they tried in the beginning not to cut as much as they did in the silent period,” Tsivian says. As editing technology improved, cutting rates rose again. “With the data,” he says, “you can watch it happen.”

Now Tsivian is using Cinemetrics to study tempo changes in a subset of D. W. Griffith movies called “rescue films,” which the director pioneered in the early 1900s. “It goes like this: the wife is in danger, and the husband is chasing to save her.” Others experimented with this narrative, Tsivian says, but Griffith invented what are now called suspense sequences. “It was Griffith who understood that we really need not see the husband all the time, that parallel editing will only increase the suspense of the film. So you show the husband at one point, and then the wife in danger, and then the burglars who are breaking into the house.” Intercutting three lines of action requires faster cutting, he says, “and this fastness adds to the interest of the chase. It is important to cut away at a point of maximum danger for the wife. We want to know how fast the husband is moving.”

Overlaying data for multiple Griffith rescue films, which he submitted to Cinemetrics himself, Tsivian hopes to glean a pattern for how Griffith varied the tempo within them. “We want to see how the cutting tape tempo changes as the abduction or attack happens, the husband learns of it, the husband grabs a taxi or steals a car, and rushes to the rescue.”

Studies like this one are the future of Cinemetrics, Tsivian says. But it will require adjustments. The database is growing rapidly, but its submissions are not standardized; human error remains a factor. Keith Brisson, AB’09, a Humanities Division database programmer who helps Cinemetrics, says the next step is to comb the “chaos” out of the data, to make it more reliable and widely usable. Tsivian and Brisson may also add a feature that generates cutting-rate data automatically. But “I will never say let’s eliminate the manual tool,” Tsivian says, “because after you have clicked through a movie, and you have made 600 clicks, you almost feel this movie is in your finger. You know its rhythm. If you watch a movie, you don’t notice cuts. If you register cuts, you have a visceral feeling of it. It’s like watching a film and then dancing a film. I always want to be able to dance the film.”