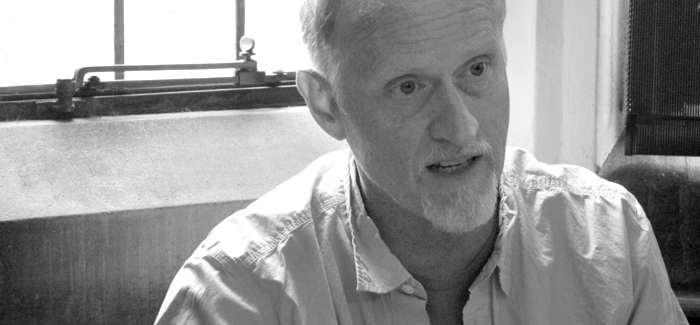

McGrath, on a recent visit to the Classics Café. (Photography by Tom Tian, AB’10)

Poet Campbell McGrath, AB’84, explains how writers are like baseball players, what’s wrong with novels, and why he was banned from several frats in the mid-’80s.

Campbell McGrath, AB’84, has published nine poetry collections, including In the Kingdom of the Sea Monkeys (2012), Shannon: A Poem of the Lewis and Clark Expedition (2009), Seven Notebooks (2008), and Spring Comes to Chicago (1996).

McGrath, who won a McArthur “genius” award in 1999, teaches creative writing at Florida International University. “Capitalist Poem #5” appears in the Winter 2014 issue of the Core.

Do you have any writing rituals or routines?

Writers are like baseball players. They do certain rituals and have certain superstitions. But I don’t. I don’t want to be reliant on any particular ritual.

My writing goes through cycles, depending on how busy I am with family and teaching and life. Right now I’m in a writing cycle. So I get up at 6:30, I drive the carpool, then I go to my office at 8 a.m., and I don’t come down until 6 p.m., day after day.

Is it pleasurable?

Oh yeah. It’s hugely pleasurable. All my life what I’ve wanted to do is write poetry.

Your wife (Elizabeth Lichtenstein, AB’84) and kids appear in your poems sometimes. Do you still write about your kids, now that they’re older?

Seven Notebooks was the last book my kids were majorly in. But by the time they became 12 or 14, I couldn’t put them in my poems anymore. They’ve gotta speak for themselves.

Elizabeth has no choice about it. She is definitely still in there.

In one poem (“Wild Thing,” from the 1993 collection American Noise) you describe your wife’s shoes as “combat boots for elves.”

That was an example of something I said to her getting into a poem: “What in the heck are those things you’re wearing? Those are like combat boots for elves.” I can’t imagine she appreciated it, but she didn’t object strenuously.

The poem we ran in the Core was from 1999. Are you happy with all of your work, or are there some early poems you wish you could strike from the record?

No. I’ve never published a poem that I’m not happy with today. I have a lot of poems that I’ve never published. Of all the poems you start, you only finish a certain percentage.

If I feel like there’s anything in the poem, I try to really work it until it becomes something. You might think it’s a long poem, and it becomes a sonnet. Or vice versa: here’s a little idea, and for some reason it keeps growing. I’ve certainly published the majority of my poems.

What do you mean exactly by majority?

I would say 60 percent. I’m going with 60 percent.

Were you ever part of the slam poetry scene in Chicago?

I came back to Chicago after college in the late ’80s, right when the poetry slam was getting started. I read up at the Green Mill in 1988 or something.

It’s exactly the opposite end of the spectrum from high modernism. High modernism pushes poetry too much toward texts and literary analysis, and slam poetry pushes it too much toward dramatic utterance. It lacks literary artifice.

There’s an oral tradition pole and a textual, intellectual pole. I like both of those poles, but I try to swing various ways in the middle.

Do you enjoy reading your work?

I love reading my work. When I was an undergraduate here, I was reading my poems all the time, at any kind of poetry event there was. After graduate school in New York City—I went to graduate school at Columbia—I was in a hipster artist group. We had the Wheel of Poets, like the Wheel of Fortune, a big giant wheel you would spin around in bars.

It’s the same kind of thing my graduate students do in Miami. They’ve got this Miami Poetry Collective. They take poetry to the streets and make it more interactive and it’s for the people.

But that’s more of a young person’s thing?

It’s a young person’s thing. I guess I read mostly at universities, book festivals, literary conferences. I read at the University last year. I was the keynote speaker at the Chicago Public Library’s poetry festival.

I’ve lived in Miami for 20 years. People would be very bored of me reading in coffee shops if I were still doing it.

Your next major project is a cultural history of the 20th century.

That’s what I’ve been working on for five or six years. I’m always writing at least two books. I thought the 20th-century book would be the next book that I would get finished, but now I want another three or four years on it.

It’s 100 poems, one per year, in different voices. Some people appear two or three times. And two people come back a lot—Pablo Picasso and Mao. I think there’s a dozen Picassos and ten Maos. Once I’m born, I become a voice too.

I have 80 or 85 of them written. And I have ideas for most of the rest. There are still some years—I don’t know what to say about 1949.

Do you ever suffer from writer’s block?

I don’t think there is any such thing, unless you’re in a catatonic state. There’s such a thing as writer’s block on a specific project. So just go down another path. Write another thing, or do some polishing or revising. Or pick up the dictionary and find some interesting words and play around with those.

If you hadn’t become a poet, what would you have done instead?

I don’t know. I wouldn’t have wanted to be a novelist. I’d much rather be a historian or an anthropologist.

Why not a novelist?

The artificiality of novels. I know that sounds silly, but how could they be any more artificial? This character has been made up, and the universe has been made up, and once you start a novel, by page five you know two or three things are going to happen.

A poem can be anything. If you read the first few lines of a poem, it could go on to be the Odyssey or a haiku, and you don’t know. There’s an unbelievable range of surprise and possibility.

I know many novelists, and that is really a long-term commitment. It’s like driving an 18-wheeler across the country all night long by yourself in the cab. It’s a long, arduous trek, none of which appeals to what I’m trying to get at. But I read novels all the time.

Your Wikipedia page says you were in a band called Men from the Manly Planet.

I don’t know why that band is on my Wikipedia page. I don’t know who put that there.

It was just three guys from our freshman dorm, Pierce Tower. One of us had talent. That was not me. One of us was demonstrably insane. That was not me either. The third guy was me.

I played a stand-up snare drum. The Violent Femmes became big around then. That was one band we were maybe kind of like. Simple, fast, rock ’n’ roll songs. Oddly, that’s the kind of music I still listen to. We had TVs onstage. The lead singer usually sang with a child’s T-shirt over his head, with eyes cut out.

We played at frats and parties in Hyde Park. The guy who was talented went on to be in some other bands—bar bands in Wicker Park. He was a philosophy major here but he’s now the NFL editor of Sports Illustrated—Mark Mravic [AB’84].

We were banned from some of the fraternities, because we sang mean songs about them. We played at the Pub once or twice. We played the Lab School once. They hated us.

That band was superfun. But none of us thought we were going to be rock ’n’ roll stars.