Allen Ruppersberg, Untitled, 1988; set of 10 lithographs, 25 1/2 x 15 in. (All photos courtesy Chicago Booth, except as noted.)

One of the city of Chicago's top modern art collections is hanging right in our own backyard.

Hidden in plain sight in the lobbies, corridors, and meeting spaces throughout Chicago Booth’s Harper Center is an astounding collection of contemporary art—paintings, neons, photographs, text, and sculptures from 75 artists, painstakingly assembled over the past eight years by a UChicago economist and his committee of five. Often overlooked, this collection is a cultural treasure of Hyde Park and Chicago.

When the ultra-modern Rafael Viñoly–designed Harper Center opened in 2004, Canice Prendergast—the W. Allen Wallis professor of economics, a Booth faculty fellow, and an amateur art collector—saw an opportunity. On the empty walls stretching between classrooms, lounges, and offices, there was room for more than just tasteful decoration: what Prendergast saw was a blank canvas, a chance to incorporate conceptual, abstract art that would add to the intellectual atmosphere of the school and of the building. Prendergast believes the abstraction inherent in most contemporary art mirrors the creation of explanatory research models that point to real-world phenomena: “Most of what we do here is based on abstraction, actually—a lot like modern art is.”

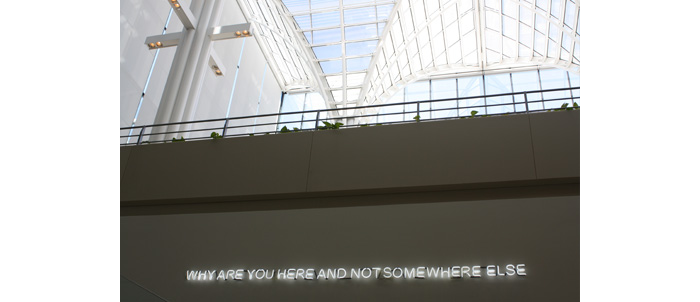

Not only students and faculty, but also staff and visitors—all passersby—can find themselves challenged by the art staring back at them from the business school walls. Nothing so explicitly embodies that concept as the neon (above) by Jeppe Hein.

So who picks the art? It’s not just Prendergast working alone. He is one of five committee members (all of whom he selected) who search for works, primarily by up-and-coming artists from around the world, and display them in the Harper Center. Three of the committee members are art-world professionals: Suzanne Booth (yes—as in Chicago Booth), an art conservator and art historian; James Rondeau, curator and chair of contemporary art at the Art Institute of Chicago; and Susanne Ghez, director of the Renaissance Society.

The Jeppe Hein neon was used as the subject of a student's convocation address a few years ago, and the student council is currently designing an app for self-guided tours of the collection. Twice a quarter, Prendergast offers guided tours that sell out in a matter of hours. Prendergast claims that in Chicago, only the Art Institute and Museum of Contemporary Art have better collections.

Members scour art fairs around the world—the big four are held in Miami, Basel, New York, and London. Though Prendergast would neither disclose the committee's budget nor estimate the worth of the collection, he says they look for as-yet-undiscovered artists largely because of the lower price tag. Whenever someone finds a gem, they pass it on to the committee, where it must be approved by four of the five members. Often, as with the painting (above) by Gabriel Hartley, the subtleties of the work cannot be appreciated except in person, so the committee members each visit the painting (this one was in Chelsea, NYC), or ask the owner to bring it to Chicago.

Faculty members fight to have certain works placed outside their office doors. The oil painting (above) by Dutch artist Rezi van Lankveld was so often requested that Prendergast had to find a compromise: he placed it on the wall between the staff and faculty lounges.

Unlike a museum, Booth is a place of work—one where art can be more of a distraction than an attraction—and nobody asked for writing on the walls. Prendergast is aware of this. “You can’t ask people to be offended,” he explains. Visitors go to contemporary art museums understanding that something there may offend them. That is not the case at Chicago Booth. Prendergast and the rest of the committee are sensitive to this fact, both when purchasing and placing the art.

For example, this landscape by Japanese artist Tomoko Yoneda shows a Serbian front line massed on a hill outside Sarajevo during the Bosnian War. Before purchasing the painting, Prendergast consulted a Bosnian faculty member, who recognized the painting's exact setting and was not only unoffended, but requested that it be hung outside his office.

Something else about Booth’s collection: it is completely free and open to the public. The collection committee see that as part of their University citizenship, Prendergast says. The Smart Museum can borrow any piece at any time, and Prendergast is working to build a formal relationship with the Department of Visual Arts, always encouraging Hyde Park's arts community to take advantage of this not-so-hidden treasure.

This commitment is perhaps best embodied by Idee di Pietra (Ideas of Stone) by Italian sculptor Giuseppe Penone. The 30-ton tree, made of bronze, cast-iron, and granite, sits outside the Harper Center, where it seems to be stretching its branches toward Ida Noyes Hall and Rockefeller Chapel, offering itself proudly and starkly to the rest of the University community.