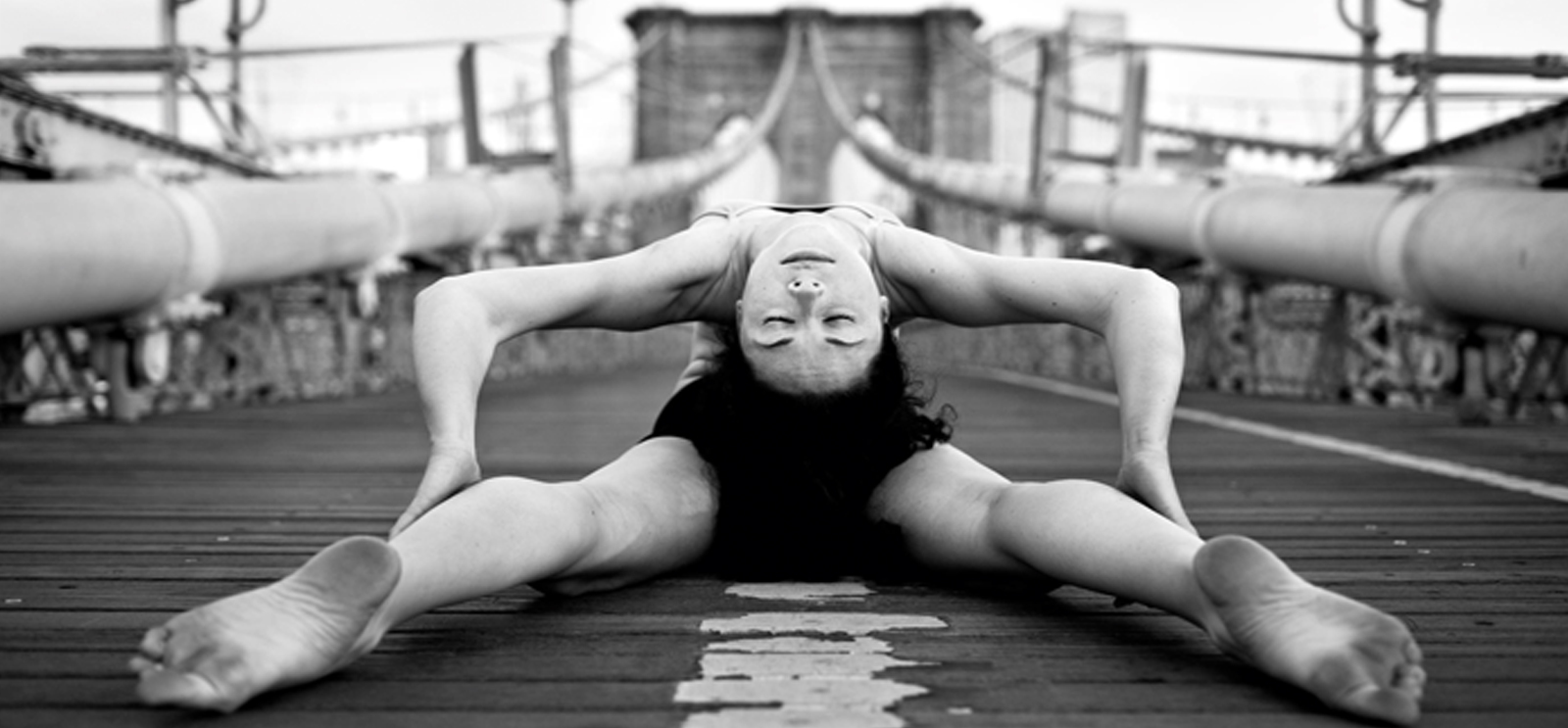

Heyman’s book of photographs and essays features acrobats outdoors, such as this pose on the Brooklyn Bridge. (Photo by Acey Harper)

Harriet Heyman, AM'72, finds herself in acrobatics.

Nearly 20 years ago, I enrolled my two toddlers in an acrobatics class at a hole-in-the-wall circus school in San Francisco. The boys stuck with it for a few years, but as they grew up, they moved on to soccer, baseball, and girls. I stayed, caught by the strange beauty that first attracted me. Since then, for more than 15 years, I have been training on trapeze.

For flying trapeze, I climb the ladder up to a narrow perch, grasp a 30-inch steel bar, and step into the air. Swinging like a pendulum, I let go, launch an aerial trick, and soar toward the outstretched hands of a muscled catcher who is twice my size and half my age. I also train on static trapeze. In static, the trapeze, mounted on long ropes, does not swing back and forth. It can, however, twist and judder and at times bind as tight as a tourniquet. I do a routine, choreographed to tango music, and work on tricks called dolphins, unicorns, Russian rolls, and meat hooks. Bruises and ripped calluses go with the territory. For me, now in my early 60s, trapeze has become a quiet passion.

Years ago, in this dilapidated gym, I reinvented myself. I was in my late 40s. With no more trouble than it took to change my diaper bag into a gym bag, I could walk out of my house and, minutes later, be among a different species. These honed men and women worked past pain at something so difficult, unusual, and stunning, and—from the perspective of the outside world—something that appeared utterly useless. I was hooked.

I read about acrobatics. I wrote about acrobatics. I took my family to every circus that came to town, from Cirque du Soleil to traveling mud shows. I flew to Paris and Monte Carlo to watch international circus festivals. I delved into the history and biomechanics of acrobatics. Mostly, I trained. And in the process, an infatuation grew into a deep bond.

In acrobatics, separate themes of my own life spiraled together: work and play, memory, friendship, solitude, discipline, frustration, risk and failure, love and desire, creativity and writing. Acrobatics became my North Star, shedding faraway light on matters close to home. Training challenged me, and not just physically. It made me question where I was in the arc of my life.

I first walked into the gym a middle-aged mom, resigned to gravity. But these athletes, amateur and otherwise, were so buoyant. They weren’t all young, but they possessed a defiant power. Being around them made me ask myself, “What does it mean to grow older?”

Somewhere along the way, I had donned the burka of sexual invisibility and passed through the marketplace unnoticed. I might have stayed cloaked and seething. But working on layouts and pinwheels, I reinhabited my body, entering a new phase that had nothing to do with seduction, mating, or procreation. Did my body disguise my self, or reveal it? Was acrobatics, late in the day, a last grasp at youth? No, it seemed more like the ideal traveling companion for right where I was now. I had found a new circle.

The circus school was a day trip through purgatory. Here we were—people of all ages, shapes, abilities, backgrounds—training, bundled up in a frigid gym that seemed two steps away from the wrecking ball, all in the name of developing skills in an art form that few in the outside world understood or cared about. Stilt walkers, jugglers, aerialists, hand balancers, tumblers, and contortionists practiced in self-defined spaces, oblivious of fliers doing tricks and plummeting into the net that stretched the length of the 80-foot gymnasium. Most students practiced in stoic silence: the same motions, hour after hour, day after day, before work, after school. Even for the youngest, strongest, and most athletically gifted, nothing came easily or without pain. Acrobatics was the great equalizer. Nobody was a star.

Every once in a while, I’d witness an instant that seared into my brain. It was an incidental motion or gesture. The acrobat wasn’t even aware of it. Unlike dancers, who rehearse in front of mirrors, acrobats can’t see what they’re doing. They feel where they are in space and intuitively make minute adjustments.

I wanted to capture these acts that defied age and gender and gravity. I started to write down these mental snapshots. These frozen moments of grace and intuition sparked the idea for my book, Private Acts.

Today few people run away to join the circus. There are more options and fewer circuses. But however expressed, the desire to break the ties that bind still burns. Who at some point doesn’t crave a new script? For most of us, it’s amorphous longing, the quiet desperation of those privileged with choices. Something about the proud defiance of the acrobat embodies that urge. Watching a body fly beyond its limits inspires hope.

I was lucky, stumbling on acrobatics. For me, it is both recreation and re-creation. It touches something that already lived deep inside me. I’m not pretending to be someone I’m not. I don’t expect acrobatics to make me thin, young, or famous. All it gives me is something simple and wondrous. Every so often, after months of frustrating practice and backsliding, a trick works beautifully. I don’t know why. When it happens, it seems natural. Without fear, inhibition, or desire, the body moves fluidly in finite space and time. After years of training, I’m learning the art of letting go. Everything that went before is distilled into one defining moment that gives back joy.

Adapted from Private Acts: The Acrobat Sublime (Rizzoli, 2011) by Harriet Heyman, photographs by Acey Harper.