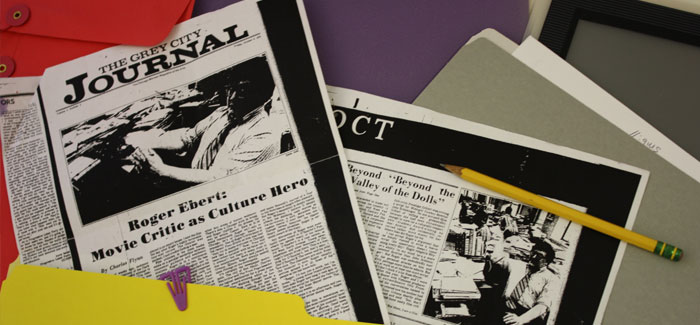

The author’s copy of the Grey City Journal’s Roger Ebert article. (Photography by Joy Olivia Miller)

The way he was

A ’70s Grey City Journal article recalls Roger Ebert’s start as a Chicago-style film critic.

In March 2012, sitting in the Chicago Maroon’s dim basement office in Ida Noyes Hall, I came across a gem. It was nearing 5 p.m., and I had spent the day flipping through old bound volumes to research an article about the newspaper’s history. After hours skimming standard stories about orientation activities, sports competitions, and campus elections, I turned to the front page of the Friday, October 9, 1970, Grey City Journal arts supplement and was struck by a shot of Roger Ebert, X’70, then a 28-year-old Chicago Sun-Times critic, leaning back in his office chair, surrounded by disheveled piles of paper.

The profile that followed, called “Roger Ebert: Movie Critic as Culture Hero,” offered an intriguing glimpse into Ebert’s life as a rising star in the film critic world, when that world was still dominated by newspapers—and by New York writers who were more famous than Ebert. I excitedly e-mailed a colleague and asked her to look up the former Maroon reporter, Charles Flynn, AB’71, MBA’77; I hoped to interview him for my article. Unfortunately, according to our records, Charles Flynn had died in 2008. I made a copy of the piece anyway and tucked it away.

This April, Roger Ebert died at 70. While preparing his Magazine obituary, I remembered Flynn’s profile and dug it out of my file drawer. The text isn’t available online, but I’ve excerpted some highlights below.

What is perhaps most important to Roger about his job is the pure existential experience of sitting in dark theaters fifteen or twenty hours a week. He speaks of watching two horror films in the Oriental Theatre on a Sunday afternoon as an event. A newspaperman at heart, Roger is as much a reporter as a critic: the movies at the Oriental show a rise in audience interest in horror flicks, which are basically Gothic in tradition, which reveals an obsession with death, which reveals ... something about America today.

Chicago as we all know, operates on clout; Roger Ebert has clout. Case in point: this summer, Paul Williams’ excellent film The Revolutionary opened. The distributors had more or less given up on the film after a disappointing run in New York. It had no advance publicity and schlocky newspaper ads. For four or five days it played to an empty house. I saw the film the day after Roger’s highly favorable, four-star review. The theater was packed; I had trouble finding a seat. Film criticism in the mass media exists on a peculiar borderline between consumer guidance and aesthetic analysis. Roger is in a continuous process of reconciling the two. He has no real critical or ideological axe to grind. One thing you’ll always find in his reviews is an honest, personal response to the film at hand. Roger calls the game that the big-time New York critics—Judith Crist, Rex Reed, Pauline Kael—play “Critical One-Upmanship.”

We all know that there is a “Chicago style” in architecture, politics, and other key areas of human endeavor. There’s also a Chicago style in living, and Roger typifies it. He dresses the way he writes. Casual. Eats at $1.50 steak restaurants. Roger isn’t only in Chicago; he’s of Chicago, hence his popularity. One of Roger’s criticisms of the recent Time article on him was that “they try to make everyone in Chicago look like a populist.” Now, Time had been rather cavalier with its facts (isn’t it always?) but there is some truth in that interpretation. Born and raised in Urbana, Illinois, Roger always looked upon Chicago as the metropolis. It’s certainly the newspaper metropolis. The city of Ben Hecht, Charles MacArthur, and The Front Page became the logical destination for a press association award-winning editor of the Daily Illni. Walking through the Sun-Times building once, Roger made a special point of taking me past the presses so we could smell the ink, see the rolls of newsprint.

Any discussion of Roger must eventually come round to O’Rourke’s pub, where he spends many of his leisure hours. O’Rourke’s is a real saloon, at 319 West North Avenue. Young newspapermen and other members of Chicago’s literati drink there. This is a free plug for O’Rourke’s, but that’s okay. I like O’Rourke’s. The owner and his wife are nice. The customers are nice. Even the bouncer is nice. Roger usually arrives around 9 or 10; most of the people at the bar know him. “Roger, I’d buy you a drink, but I’m a broke,” a young writer friend offers. He then asks Roger how long it took to write the script for Beyond the Valley of the Dolls, the Russ Meyer movie. The answer is six weeks. “You wrote it in an afternoon and you know it,” the writer shoots back. Roger laughs. ... Earlier this year, Roger and I were having dinner with Viennese producer-director extraordinaire Otto Preminger, and the conversation turned to BVD. Roger related how his mother had called him from Urbana shortly after the film opened and said, “Son don’t youworry about those nasty film critics.” Roger’s reply, “But Mom, I am a film critic!”