Theodore Dreiser mentions Yerkes Observatory in The Titan. (Illustration by Allen Carroll)

A bookcase full of potboilers, mysteries, satires—and even some great books—have the same backdrop: the University of Chicago.

It’s an aura that’s hard to explain. Maybe it blows in off the lake from the Point, or percolates in the Indiana-limestone buildings that house Mr. Harper’s university. Perhaps it wafts out of the Woodlawn Tap or lingers from that radiant 1942 day under the west stands of Stagg Field.

Wherever it comes from, the atmosphere that surrounds the University community has inspired hundreds of writers—some geniuses, others decidedly not—to try to capture the character of the place in fiction. Gray stone towers, the grassy Midway, whitecapped Lake Michigan, and the endless stacks in Regenstein Library have all been written, often very little changed, into the pages of novels and short stories.

From Theodore Dreiser and Edna Ferber to Andrew Greeley and Sara Paretsky, authors—many of them alumni—have used the University and its environs not only as backdrops but also as symbols.

At times the University of Chicago even functions as a novel’s central character—be it hero or villain. Such books are usually most avidly read by members of the immediate community. Hoping to uncover hints of scandal in a local roman à clef, resident readers can also quickly gauge authorial venom. As one professorial collector of University fiction has noted, “If the University is named, and the architecture Gothic, the writer is usually moved by affection; if the name is changed, and the architecture either grotesque-Gothic or ‘collegiate Georgian,’ the writer is usually motivated by revenge.”

In Chimes, Eureka University’s “half-finished” buildings are of stone, but compare unfavorably to “the lovely intimate quads” of Cambridge. The narrator of professor-turned-novelist Robert Herrick’s 1926 book is Professor Beaman Clavercin of the Department of General Literature, who recounts Eureka’s first 30 years, from its untidy but heroic days under President Harris through the more staid command of Harris' successor, Dr. Doolittle. Clavercin's own doubts about the success of the enterprise are plain. “The very sight of a dissertation or thesis” gave him “an attack of mental nausea. Somehow all this applied scholarship was killing the root of the matter it was applied to.”

Another acerbic assessment comes in Georg Mann’s The Dollar Diploma, set in the early 1950s. Tom Mears, humanities editor at the Fox University Press, watches the resignation of President Raynsford, the subsequent dismantling of Raynsford’s “Individualized Education” curriculum, and the university’s new obsession with fund-raising, urban renewal, and the onslaught of McCarthyism.

Mann's choice of title reflects a perceived bottom line: “Students bright enough to get into Fox are bright enough not to put up with the dullness of the average lecturer. True, 90 percent of them are here to get the dollar diploma, the working ticket for a job. Consequently, they get it the least painful way. They take the reading list, vanish, and reappear on examination day.”

The University probably gets its best character reference in Winds Over the Campus, written by longtime English professor James Weber Linn, whose English-professor narrator, Jerome Grant, has been at “the University” since his own student days in the 1890s. Although the events that unfold reflect the social malaise of the 1930s (racism results in a coed's suicide; Red-baiting nearly claims a football player’s life), Grant remains optimistic: “Yes, there had been great change in the twentieth century, he thought. ... For had not the University, in its little corner, been a part of the influence towards this change? ... It had somehow induced hundreds of thousands of young people to think about life, instead of taking life for granted.”

An ivory fortress of intellectual angst, the University is regularly depicted as a place on edge, politically and psychologically. Tensions flare repeatedly—between men and women, liberals and conservatives, highbrows and philistines, blacks and whites.

Even the earliest novels describe this unrest, often focusing on the liberation of women and the new, discomforting freedom between the sexes at the pioneering, coeducational university. In Edna Ferber's The Girls (1921), for example, young Charley (representing the third generation of women named Charlotte in a South Side family) heads off to the U of C, where she shocks her conservative family by enrolling in a business-executive training program for women: “This new course would introduce into business the trained young woman of college education. Business was to be a profession, not a rough-and-tumble game.”

In James T. Farrell's 1932 short story “All Things Are Nothing to Me,” the tension builds as a Chicago student from a Catholic family adjusts to life in a secular institution. “Aunt Margaret, sure ’tis a terrible place, I tell you,” says Joe, the student. “Why, they take every Catholic student who goes there and lock him up in one of the towers of the main library buildings and keep him there until he promises he'll become an atheist.”

Much of the psychological tension flows from the rigorous nature of the University's academic enterprise. In Philip Roth’s Zuckerman Bound, Nathan Zuckerman remembers his undergraduate life at the U of C during the late 1940s: “Inspiring teachers, impenetrable texts, neurotic classmates, embattled causes, semantic hairsplitting—‘What do you mean by “mean”?’ His life was enormous.”

Enormity is not for everyone, and picaresque novels that begin with the protagonist leaving the University are fairly common. Wilton Barnhardt’s Gospel opens as a theology student, stuck on her dissertation, is sent in search of an errant professor, last sighted traveling around the world on the department's credit card. In Rome, she recalls life in Hyde Park: “Going back to Chicago, Lucy realized, meant going back to the thesis and the approaching deadline and the word-processing lessons so she could write and edit it, and back to the fighting over who got what cubicle at Regenstein Library.”

Regenstein is the jumping-off point for Geraldine Coleshares, the heroine of Laurie Colwin’s Goodbye Without Leaving. Hooked on rock and roll (she picked the U of C because of the South Side’s reputation for rhythm and blues), Geraldine eventually finds herself wishing to abandon the dreary life of “a graduate student, sitting in the library at the University of Chicago, getting older and older, trying to think of a topic for my doctoral dissertation and, once having found the topic, trying to write about it.”

Occasionally, fictional students do leave with degrees. In Susan Fromberg Schaeffer’s Falling, Elizabeth Kamen—a woman struggling with her past and her ethnic background—finally earns her Ph.D. Some of her difficulties had been predicted: “All summer, people had told her about the University, how hard it was, how only geniuses went there, how everyone was eccentric, how everyone cracked under the strain.”

Book after book serves to establish the stereotype of Chicago’s eccentric and left-leaning students—an image that Sara Paretsky plays with in Indemnity Only. Early in the plot, detective V. I. Warshawski is visited by a man claiming that his son, who'd been on the fast track to an MBA, has been led astray by a girlfriend, the daughter of a union organizer: “It’s just that—they've been living together in some disgusting commune or other—did I tell you they’re students at the University of Chicago?” In Hyde Park's local-color fiction, professors tend to fall into several set categories: the emotionally draining, self-centered neurotic; the rumpled but lovable academic with strong appetites; the physicist with a heart; the psychiatrist without one.

A fine example of the iconoclastic scholar is the star of Gospel, Patrick O’Hanrahan—erstwhile Jesuit priest, founder of the U of C theology department, alcoholic, and eccentric: “He was standard academic professor-emeritus issue: a potbelly, a good suit now worn and creased around his girth, and even in repose an aura, his own weather system swirling around him.” (In what might be authorial wish fulfillment, the older disheveled types often win the hearts of younger, far more attractive, female scholars.)

In Philip Roth’s Letting Go, U of C English professor Gabe Wallach—neurotic, sarcastic, and busily attempting to manipulate other people’s lives—emerges from Cobb Hall after a dog-eat-dog faculty meeting into the relative serenity of the quads: “The Gothic archways attested to the serious purpose of the place and made me want to believe that we were all better people than one would suppose from the argument we had just had.”

The protagonist of Saul Bellow’s Herzog, a professor of intellectual history, faces the mess of his life—two ex-wives, a friend’s betrayal, separation from his only child—while confronting all of modern man's dilemmas and contradictions. Moses Herzog’s interior deliberations are reflected in the details of his exterior surroundings.

Driving on Woodlawn Avenue, “a dreary part of Hyde Park, but characteristic, his Chicago,” Herzog observes its urban ugliness: “... massive, clumsy, amorphous, smelling of mud and decay, dog turds; sooty facades, slabs of structural nothing, senseless ornamented triple porches with huge cement urns for flowers that contained only rotting cigarette butts and other stained filth; sun parlors under tiled gables, rank areaways, gray backstairs, seamed and ruptured concrete from which sprang grass; ponderous four-by-four fences that sheltered growing weeds.”

At the same time, he also sees its consolation: “And among these spacious, comfortable, dowdy apartments where liberal, benevolent people lived (this was the university neighborhood) Herzog did in fact feel at home.”

For readers who also have called the University of Chicago home, real landmarks stand out in each fictional version of Hyde Park. The bells of Mitchell Tower ring the hour in Letting Go. Detective V. I. Warshawski takes a break on the ‘C’ bench in Indemnity Only. In Pearl Buck’s Command the Morning, a worried young physicist crosses Stagg Field, his collar turned up against the Chicago cold. Even the Valois (“See Your Food”) cafeteria on 53rd Street makes a cameo appearance in Scott Spencer’s best-selling novel of teen obsession, Endless Love.

And all past or present residents should recognize the locale of this rendezvous from Barbara Michaels’ academic mystery, Search the Shadows: “We ended up on the South Side, near the university... . The place he chose was obviously a popular student hangout; two patrons had their heads bent over a chessboard and I noticed a row of encyclopedias on a shelf behind the bar.” Jimmy’s, in case you hadn’t guessed.

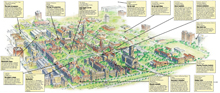

A drink at Jimmy’s is the logical place to end—or start—a journey through fictional Hyde Park. To begin your own tour, we’ve provided a map (pdf, jpg) and a bibliography. Choose a book and start exploring.

UChicago-based fiction

Wilton Barnhardt, Gospel (1993).

Saul Bellow, X’39, Herzog (1964). Bellow, who taught in the Committee on Social Thought from 1962 until 1993, also uses U of C settings in The Adventures of Augie March (1953) and The Dean’s December (1982).

Pearl Buck, Command the Morning (1959).

Laurie Colwin, Goodbye Without Leaving (1990).

Theodore Dreiser, The Titan (1914).

James T. Farrell, X’29, “All Things Are Nothing to Me,” in The Short Stories of James T. Farrell (1941) and “The Philosopher,” in An Omnibus of Short Stories (1956). The author of the Studs Lonigan trilogy (1932-53), Farrell wrote a number of stories set in Hyde Park.

Robert Herrick, Chimes (1926). That same year, Linn, who taught English at the University for 40 years, published another novel set at the U of C, This Was Life.

Georg Mann, AB’35, The Dollar Diploma (1960).

Barbara Michaels, Search the Shadows (1987). “Barbara Michaels” is the pseudonym of a College alumna, with a PhD from the Oriental Institute, who also writes under the name of “Elizabeth Peters.”

Sue Miller, Family Pictures (1990).

Sara Paretsky, AM’69, MBA’77, PhD’77, Indemnity Only (1982).

Robert Pirsig, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance (1974).

Philip Roth, AM’55, Letting Go (1962), and Zuckerman Bound (1985). Roth was an instructor in English at the University in the 1950s.

Susan Fromberg Schaeffer, AB’61, AM’63, PhD’66, Falling (1973).

Scott Spencer, Endless Love (1979).

Richard Stern, “Ins and Outs,” in Noble Rot (1989). Stern is the University’s Helen A. Regenstein professor of English language & literature.

Edna Ferber, The Girls (1924).

Andrew Greeley, AM’61, PhD’62, Lord of the Dance (1984). Greeley is a research associate at the University-based National Opinion Research Center.

James Weber Linn, PhB 1897, Winds Over the Campus (1936).

Side trips

The insider’s guide to mysteries with Hyde Park or University backdrops can be found in a new book by Alzina Stone Dale, AM’57. Her Mystery Reader’s Walking Guide: Chicago (1995) includes a walk through the University campus and the Hyde Park neighborhood, following the paths of mystery writers and their sleuths.

A new book from the University of Chicago Press—An Unsentimental Education: Writers and Chicago, by Molly McQuade, AB’81—asks 21 leading novelists and poets who have taught or studied at the University of Chicago to reflect on their Chicago experiences. Saul Bellow, Philip Roth, Susan Fromberg Schaeffer, and Richard Stern are among those writers interviewed.

Jane Chapman Martin, AM’90, is manager of editorial services at Northwestern’s J. L. Kellogg Graduate School of Management.

Infographic

A drink at Jimmy’s is the logical place to end—or start—a journey through fictional Hyde Park. To begin your tour, we’ve provided a map and bibliography.