istockphoto.com

Dylan Walsh, AB’05, reflects on the full life his uncle lived with a transplanted kidney.

Emerson, Lake, and Palmer released its second studio album, Tarkus, in 1971. It landed in America on August 14 and every day after that my uncle, who was then 17 years old and a drummer, descended to the basement of my grandparents’ house, set the record on the turntable, set the stylus to the record, set his headphones on his ears, and played along. Hours later he would emerge from the dark stairwell. This was his late-summer routine. He likely took evening trips to nearby Playland for rides on the Dragon Coaster—his clicking ascent cut short by the sound of wind, the rising of his stomach. On October 23, summer well over, he was driven to Boston for a kidney transplant.

He didn’t mark the 10-year anniversary of the transplant, but the 1982 release of Blade Runner provided a belated, indirect celebration. My uncle had many favorite movies. Blade Runner was his favorite-favorite. Who knows how many times he sat down before Harrison Ford’s apathetic stare, the hymnlike synthesizer of Vangelis? He boasted tirelessly about the movie’s uncompromising vision, as though he, not Ridley Scott, had been its director. I never understood.

The thing was, kidney transplants in 1971 were small-scale moon shots. The medicines were experimental. People wondered about somebody else’s organ in your gut. Life expectancy—of the kidney, of the recipient—was unknown.

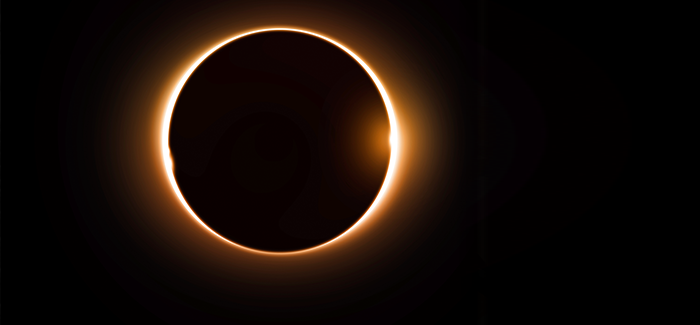

For his 20-year transplant anniversary, in 1991, he did organize a celebration. He flew with his wife and closest friends to Kona, Hawaii, where he hired a helicopter on July 11 to lift them above the gray skirt of clouds spread low over the ocean. A good day for a ride: that morning, the earth aligned with the moon, which aligned with the sun, and the fire-rimmed darkness of a full solar eclipse descended, the orange ring like a portal opened on a second world.

He and I celebrated his 30-year anniversary together, watching the shadow of Mount Hood from 12,000 feet as it raced eastward into nothing. He had flown out West to Oregon after months of physical training, and the drifting moon replaced headlamps as we set out at midnight. We walked in single file behind our guide toward the peak, which loomed in silhouette, almost touchable, against the strange multitude of stars. The air became thin. We couldn’t make summit because of avalanche risk, our guide told us, so we sat in chill on the cusp of the final push. We carved snow thrones for ourselves below the open night. Slowly, the bruise of dawn lit fire and the day broke behind us. The mountain’s long shadow retreated in silence over the treetops below. Then back down we hiked.

Thirty years on one borrowed kidney was a surprise, and so was 40, in 2011, when he and his brother booked a Zero G flight that launched outside of San Francisco. They boarded the seatless, padded 727. The plane took off, nosed high, then dipped sharply in a series of parabolic arcs. For a total of about seven minutes, passengers were weightless. “Why go to space?” my uncle would always ask after the trip. He showed pictures of the two of them, two brothers, sailing weightless through the fuselage.

Eventually, of course, the journey ended. He died on January 17, 2014, just shy of his 60th birthday and the 43rd anniversary of his transplant.

I stood in his apartment the next night. Friends streamed through to shake hands and pat backs in murmuring white noise, to offer my aunt, his wife of 23 years, condolences. We told stories, but we also read them in the library of objects spread across the townhouse. My uncle was not rich, but he was a collector: posters and pictures, crystal figurines, mementos at every step to mark the places he had been and the strange and astonishing wealth of life that he had witnessed, from Antarctica to the Galápagos to—almost—the North Pole. That was perhaps his only regret, not traveling to the North Pole in the company of Neil Armstrong like Sir Edmund Hilary did in 1985.

That night, watching the crowd arrive and depart, I thought about Blade Runner. In the movie, the androids, called replicants, return to Earth from their heavenly posts in search of their creator, a reclusive scientist who gave them only four years to live. They want more life. Four years is not enough.

They’re denied the gift. Harrison Ford hunts them down, one by one. In the closing scene he watches as his final bounty, the nimble and oddly charismatic leader played by Rutger Hauer, slumps in the rain, tired and sick, recounting his short, refulgent life. “I’ve seen things you people wouldn’t believe,” Hauer proclaims. “Attack ships on fire off the shoulder of Orion!” Ford sits silently. Hauer continues to list his astral visions.

“All those moments will be lost in time, like tears in rain,” he says, looking at Ford. And then: “Time to die.” He casts his eyes down. He dies.

Dylan Walsh, AB’05, is a freelance journalist living in Connecticut. He covers science, the environment, and criminal justice.