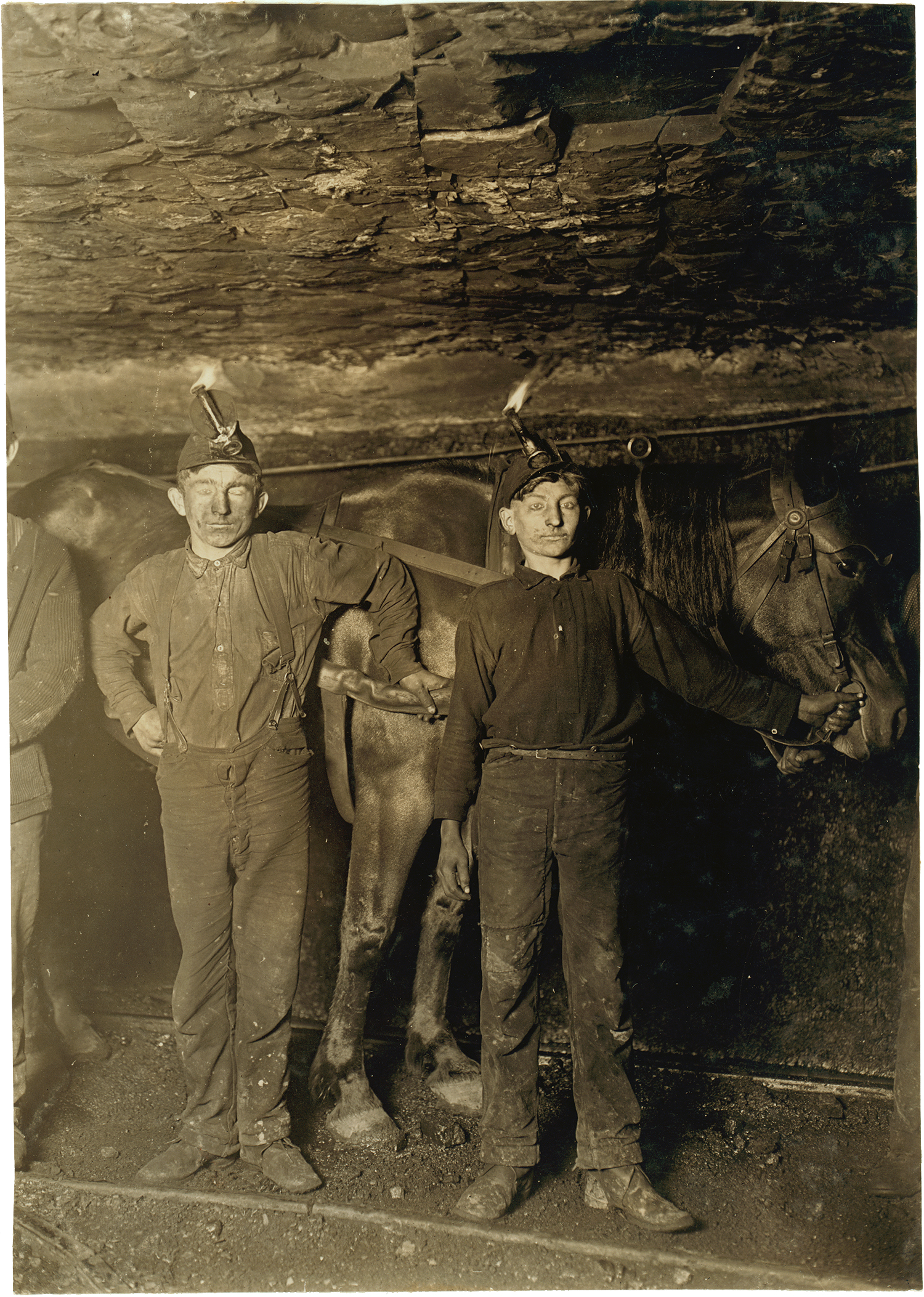

Nearly two million children ages 10 to 14 were at work in the United States by 1900. Between 1908 and 1911, Lewis Hine photographed hundreds of these young laborers, including Sadie Pfeifer. At the time this photo was taken, she had been employed in a cotton mill for six months. (Photography by Lewis Wickes Hine, EX 1904)

Lewis Hine, EX 1904, captured the changing face of American labor.

In 1908 photographer Lewis Wickes Hine, EX 1904, visited a cotton mill in Whitnel, North Carolina, where he met a little girl employed as a spinner. When Hine asked how old she was, the girl demurred. “I don’t remember,” she told him. After a moment, she added, “I’m not old enough to work, but I do just the same.” In his record of the encounter, Hine noted the girl’s daily wage: 48 cents (about 13 dollars today).

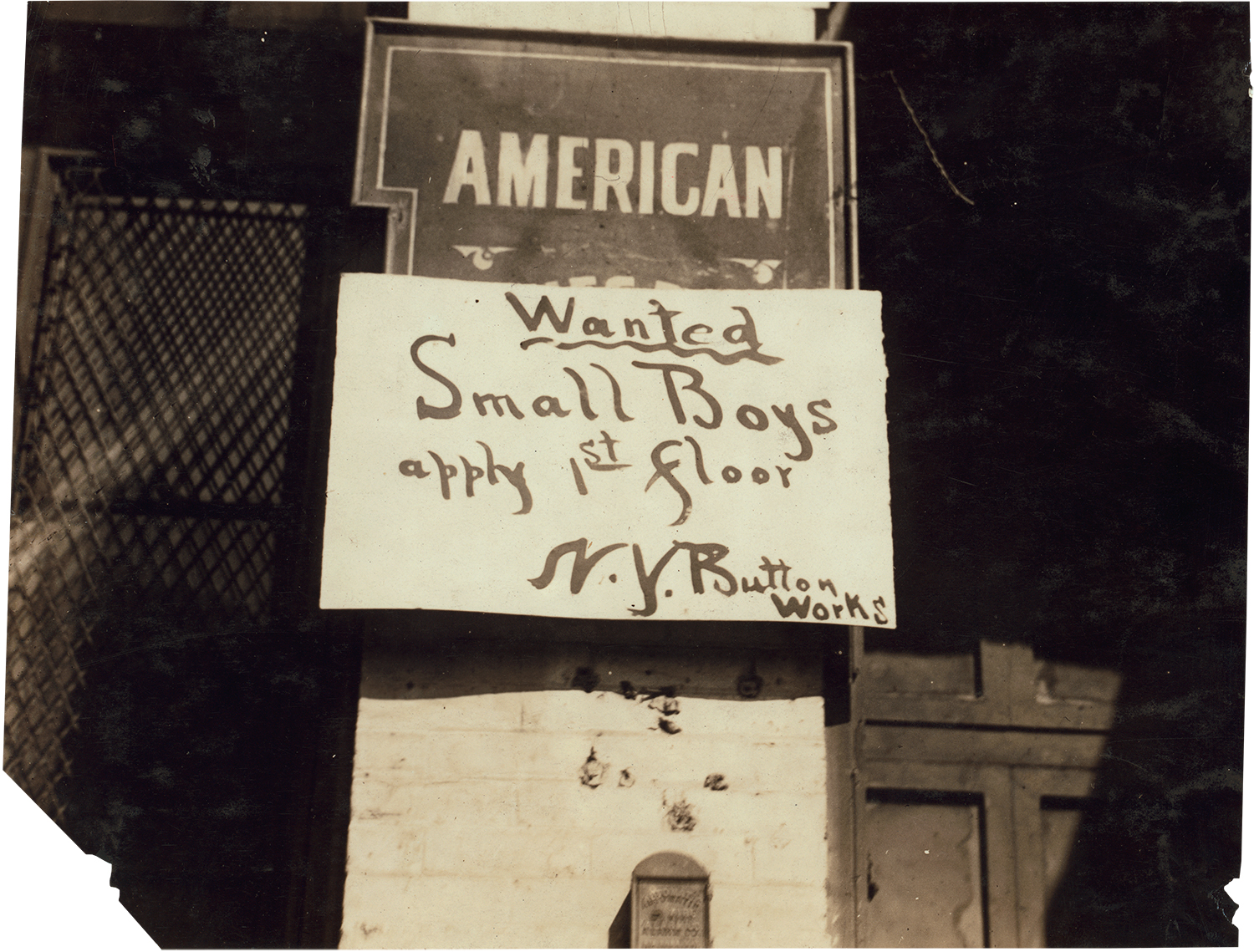

Industrialization brought children who previously might have worked on family farms or in domestic service into factories and urban sweatshops. Children’s wages helped their families survive and might have accounted for as much as 20 percent of their household’s total income. In 1900 children ages 10 to 14 made up 6 percent of the American workforce. Many were recent immigrants.

From 1908 to 1911 Hine traveled around the country, documenting the lives of young workers for the recently formed National Child Labor Committee (NCLC). When the images were published in NCLC pamphlets and in popular magazines, they shocked many Americans and spurred efforts to reform and strengthen labor laws.

“If I could tell the story in words,” Hine said of his work, “I wouldn’t have to lug a camera.”

Hine’s own working life began at 18, after the death of his father. Alongside the various jobs he held to support his mother (factory laborer, janitor, bank clerk), Hine took extension courses in art and stenography at the University of Wisconsin. He earned a teaching certificate at the Oshkosh Normal School and went on to study at the University of Chicago under educational reformer John Dewey. In 1901 Hine moved to New York to teach at the Ethical Culture School, which offered free high-quality education to poor children.

Millions of Europeans were pouring into the United States in 1903, when Hine bought his first camera. For one of his early photographic projects, Hine hauled his bulky equipment to Ellis Island in hopes of chronicling the experiences of these newcomers.

He continued to trace the immigrant experience through the early 1900s. In 1907 the NCLC commissioned Hine to photograph home labor in New York City’s teeming tenements, where immigrant children, along with their parents, made clothing and assembled artificial flowers.

By 1908 Hine had left his teaching position and was working primarily for the NCLC. With his wife, Sarah Ann Rich, he crisscrossed the country, sweet talking factory owners into allowing him to take pictures. If he was refused entry, Hine would wait for a shift change and photograph the young workers on their way home.

Hine’s notes were brief but evocative: “7 a.m. Boy (‘Bill,’) carrying milk. In summer he works in the glass factory and keeps two cows too.” “Sonny and Pete newsboys. One is six years old. They began at 6:00 a.m.” “Gastonia, n.c. Boy from Loray Mill. ‘Been at it right smart two years.’”

The publication of his images helped bring about gradual changes, including the creation of the first federal bureau focused solely on improving the lives of children and families. In the early 1900s, the Supreme Court narrowly overturned several efforts to ban child labor at the federal level, but public opinion had shifted decisively against the practice—thanks in no small part to Hine. The chair of the NCLC said Hine’s work was “more responsible than all other efforts” in rousing the public. In 1938 the Fair Labor Standards Act ended dangerous child labor and offered new protections for minors.

After parting ways with the NCLC over a salary dispute, Hine maintained his interest in labor issues but found a new tone. His images of the construction of the Empire State Building celebrated the daredevil feats of the workers who raised 57,000 tons of steel to frame the building. The images “have given a new zest ... and perhaps, a different note in my interpretation of Industry,” Hine wrote.

In the 1930s Hine took on small freelance projects but worried his images had fallen out of fashion. His reputation for difficulty, too, scared off potential employers. One former boss praised his talent but noted he was a “true artist type” who “requires some ‘waiting upon.’” Hine applied multiple times for a Farm Security Administration project documenting the impact of the Great Depression, but the head of the project felt he was too uncompromising. When Hine died in 1940, he was destitute and his home was in foreclosure. The photographer who had made a career of capturing the devastation and majesty of American labor couldn’t find work.