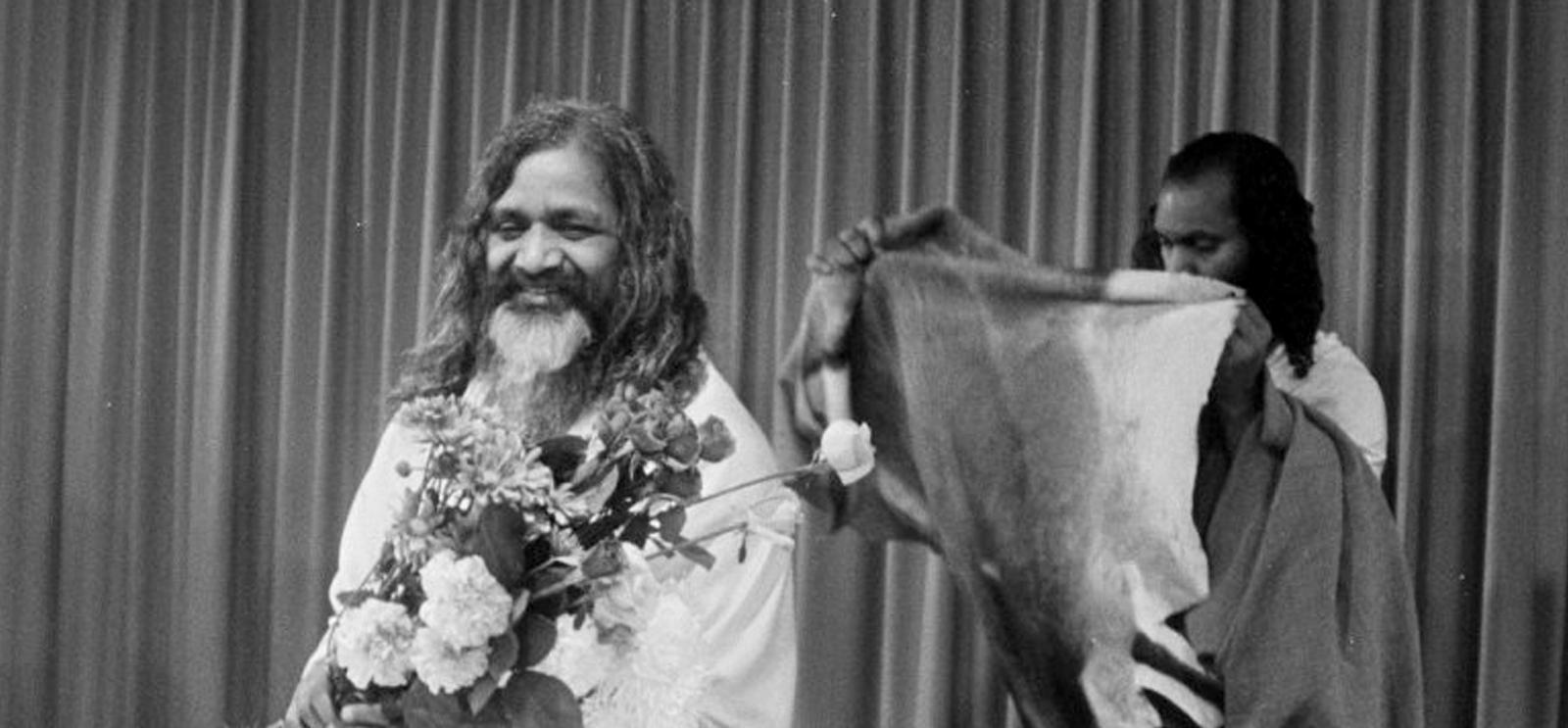

Some say John Lennon was inspired to write “Sexy Sadie” after a dispute with Maharishi. The song’s original first line was “Maharishi, what have you done.” (Photo courtesy National Archives of the Netherlands)

Excerpt from Greetings from Utopia Park: Surviving a Transcendent Childhood by Claire Hoffman, AMʼ05.

We climbed into our rusted, wood-grained Pinto, Mom turned the key, and the engine sputtered and spat until it finally turned over. The car was freezing—underneath the front floorboards, a large hole had rusted out that winter, and even though Mom had put mats down, it was impossible for the car to get warm, and the smell of gasoline was overwhelming. Mom and Stacey began arguing again and I looked out at the snow-covered campus and tuned them out, trying to imagine myself as a fifties starlet being transported from my penthouse to a luncheon.

As we turned onto Zimmerman Boulevard, I saw a group of angry-looking people standing next to the entrance of campus, holding signs. “Hindu Cult,” “Transcendental Meditation Is a Cult!” “Maharishi Brainwashes Followers.”

I read the signs quickly, slightly terrified by the jagged hand lettering.

“Mom,” I asked, “what is brainwashing?” I imagined someone pouring water into my ears, then sloshing it around.

She turned to look at the protesters, and then sped up, her face uneasy. “Those people are insane, Claire. Ignore them. Stay away from them.”

Mom reached back and pushed the seat forward to let me out of the back. The Pinto shuddered and stalled, and I looked around to see if anyone had noticed. I gave her a cautious smile, but she was staring forward, her shiny brown hair creating a mask around her face. She was still angry. I reached across the old cracked pleather seats and gave Mom a hug. Underneath her snowy boots, I saw the hole in the floorboard by the driver’s pedal. Through the open wound of the rotting metal, the dirty snow of the street was just inches away.

“I’ll see you at lunchtime,” she grumbled.

It was around this time that I began to see cracks in the Heaven on Earth realm we’d been living in. My brother had watched his friend’s father, Ed Beckley, fall apart after his Millionaire Maker program filed for bankruptcy in 1987. Ed was unable to make good on the money-back guarantee demands from the 40,000 customers who had paid $295 for his get-rich-quick program. Nearly all of his 560 employees were fired. (Later Ed was sentenced to federal prison for wire fraud.)

The First Age of Enlightenment Credit Union went into receivership in 1985 after it became overextended. A local “Siddha-owned” oil brokerage firm in Fairfield was ordered to pay over $100,000 in damages to an employee who said he was fired after driving a “rival guru” to the airport.

In 1989 International Trading Group Ltd. filed for bankruptcy after federal regulators accused the commodity firm of bilking investors of more than $450 million. The Fairfield office was, in those final years before it went bust, reportedly the top money producer for the national firm, according to the Chicago Tribune. Now it was closed and many of the meditators who worked there were scrambling to find other jobs.

When I was in sixth grade, Maharishi decided that we would become experts in something called Vedic Math. One morning, we all lined up, then headed outside under a flat gray sky, the wind cutting across the open plains with a wicked bite. The girls around me fell off into small groups, and I found myself walking to the side, preoccupied with my own thoughts.

In my pocket, I had a vial of lip gloss that I had talked my mom into buying for me at the drugstore. It was called Kissing Potion, a name that I found totally humiliating, but I was too interested in the wet look that it offered to let the name put me off. I whipped out the small, clear tube and ran a dab over my lips, then stashed the tube away before anyone could catch me preening. Across the meadow, the boys’ class was walking toward us, led by their teacher Mrs. Greenley.

We met at the center of the field, and I stared down at the ground, avoiding eye contact with any of the boys. Mrs. Greenley and our teacher Mrs. Hall greeted each other with a perfunctory “Jai Guru Dev” and traded groups. Some of the bolder, early-breasted girls had made friends with the boys and they said hello to each other in a sophisticated and enviable way.

We followed Mrs. Greenley the rest of the way up the hill into her classroom. She was my least favorite teacher, the mother of my least favorite classmate, Erin. The sixth-grade boys’ classroom was on the opposite side of the lawn from ours. With its high wood ceilings and dark green indoor/outdoor carpeting, it had been the TV lounge for the old Parsons College dorms, and it retained a slightly seedy, dank smell. As we filed in, Mrs. Greenley told us to go find a spot in the corner for guided meditation.

I sat down at a desk, feeling anxious. Math was a subject that had never particularly challenged me until this year. I had a robust memory and had easily memorized all the multiplication tables. Mom was good at math, and said it was in our genes. “Your grandfather is an engineer, you can do this,” she would say when helping with my homework. It seemed to work—until that fall.

We had been told that Vedic Math would be blissful for us but it hadn’t been for me. The computational methods were based on sixteen sutras that are directly derived from Atharva Veda, one of the four main branches of ancient Vedic literature. Our teacher told us that Vedic Math made everything easier by replacing large numbers with small numbers and breaking computations down into simple steps that you could do in your head. She also said that Maharishi had said the practice of Vedic Mathematics helped to create a general state of awareness, while at the same time focusing on a specific point. Cultivating that ability to maintain the wholeness while focusing on the parts of knowledge, he said, would allow us to live (even more?) in accord with Natural Law.

How did it work? For example, to multiply, you used the third sutra, Urdhva Tiryagbhaym, which meant “vertically and crosswise.” A sutra was just like a mantra, but instead of a sound, it had a meaning. Instead of doing 33 x 12, you would use the “unit digits” 3 and 2, multiply them and get the number six. That was the vertical answer. Then, Mrs. Greenley said, the units digit of each number is multiplied by the tens digit of the other number and these two numbers are added. I was bleary eyed at this point—were we still talking about numbers or was this an SCI [Science of Creative Intelligence] lesson with some hidden philosophical message?

Mrs. Greenley continued, writing on the board. The crosswise multiplication would give the answer: (2 x 3) + (3 x 1) = 9. Nine, she said, was the tens digit of the answer. Then the two tens digits are multiplied, vertically, to get the hundreds digit of the answer, three. Three, nine, six! She wrote out the numbers on the board, and it was as if she had completed a magic trick. It seemed more complicated to me than it needed to be, but Mrs. Greenley insisted that we show our work on the page. For guidance, she had hung a long handmade banner on the wall, next to Maharishi’s principles of SCI, which listed the sixteen sutras.

“Even young children take delight in this approach to mathematical problems. Their faces shine with joy and amazement as they learn to add, subtract, multiply, and divide,” one of the math teachers was quoted as saying in an article about Vedic Math in the school newsletter. “Often the children burst into peals of laughter as they quickly move through long rows of previously tedious computation.”

As for me, I was utterly confused by even basic questions of multiplication. Although the Vedas were credited as the basis for all of the Knowledge that our Movement followed, we didn’t actually read any of them. Instead, our knowledge came from Maharishi’s Enlightened illumination and translation of them. The way my teachers explained it, he was able to bypass the extra stuff that Hindus and Indian civilization had layered on over the centuries, motivated by human history and greed. Maharishi’s translation of the Vedas was essential and pure.

Living in Iowa in the 1980s, it seemed that Maharishi seemed intent on making Fairfield—and our lives here—more closely resemble the ideal ancient Vedic civilization he was always envisioning.

Sometimes this brought true blessings, at least if you were a kid. That year, word was sent down that—in order to have a more blissful Vedic family experience—we should have a two-hour lunch break during the school day. Our teachers had seemed a little stunned when they delivered this news to us, perhaps wondering where that extra hour of class time was going to come from. Mom wasn’t thrilled either—there was panic in her voice when she got the sheet from school. “What am I supposed to tell them at work?” she asked. “I get paid by the hour! That’s two less hours!”

I was, however, thrilled, because we were spending less and less time doing actual schoolwork. After all, work was effort and life was meant to be effortless. The school administrators argued that we didn’t need as much “time on task” since our consciousness was being raised by Maharishi’s programs. Science, Maharishi said, was the language of the West. In order for Americans to understand something, it had to be scientific. On the walls of our classrooms and everywhere you looked on the Maharishi university campus, there were elaborate charts and diagrams showing how Maharishi’s interpretation of Vedic knowledge was scientific. What did “scientific” mean? It meant that you could prove that Maharishi was right. There were laboratories on campus where scientists worked for years, proving that Maharishi’s Knowledge was scientifically accurate. More and more, Maharishi’s Vedic Knowledge seemed to be flowing into our community at an unstoppable pace, codifying every aspect of life.

But the Vedic science that came to monopolize our lives was Maharishi’s Ayurveda, his interpretation of the ancient Vedic science of health and the body. Overnight, Ayurveda became the organizing principle of how members of our community looked at themselves and the way they lived their lives. According to Ayurveda, there are three different body types, or doshas—Vata, Pitta, and Kapha. These correspond, respectively, to air and space, fire and water, and earth and water. Maharishi didn’t want us just to understand our individual doshas but encouraged us to see the whole world according to this division. There were Vata, Pitta, and Kapha times of days, seasons, qualities, tastes, and so on.

Maharishi sent doctors from India to come to Fairfield and visit the Maharishi School. A creaky old Indian man named Dr. Triguna taught us how to take our own pulses and diagnose any imbalances in our doshas. A handsome young doctor named Deepak Chopra, who we were told was Maharishi’s personal physician, came and talked to us about meditation and physiology. At a school assembly, he also lectured us on balancing our doshas to connect with the Unified Field. Everything was about curing imbalance, smoothing out any physiological irregularities so that we could be a perfect reflection of the Laws of Nature.

Now, every moment of every day had a prescription from Maharishi on how to be and how to act. According to Ayurveda, one should awaken at six o’clock in the morning so as best to align oneself with the rhythms of nature. Instead of rolling out of bed and taking a shower, we were meant to give ourselves a full body massage—an abhyanga—using Maharishi Ayurveda oils (also chosen according to our specific body constitution or dosha). This was followed by tongue scraping, gargling with oils, body scrubbing, copious herb taking, and then of course asanas, pranayama—breathing techniques—and finally a lengthy meditation.

Maharishi Gandharva Vedic music was the sound track we were supposed to play throughout these lengthy prescribed rituals. We were told it was to be kept playing in empty rooms when you weren’t there in order to balance the energy of your living space. The wiry sound of the sitar, the pounding of the tabla, the tinkling keys of the santoor—this was a constant backdrop wherever I went—coming from small CD players in empty rooms set to play the healing sounds on a loop. The music was selected according to the season and the time of day, again, to be better aligned with nature.

Even at school, before our twice-daily meditations, we had to do asanas, and then pranayama breathing, and then five minutes of taking our pulse to balance our doshas. Lunchtime was equally ritualistic. The lunch hall was filled with people who were in the midst of a popular Ayurvedic cleanse—panchakarma—which required them to get daily enemas, eat a strict and spare diet, and take lots of herbs along with spoonfuls of ghee, or clarified butter. They received hours-long oil massages at the Maharishi Ayurveda Clinic that had opened on the edge of campus, and soon it felt like every meditator had a slightly greasy sheen. The women wore soft pastel-colored turbans to hide their oil-soaked hair. Those turbans became a status symbol of sorts—these women were aggressively pursuing Enlightenment.

After our two-hour Vedic lunch break, we’d read from the Rig Veda in history class. In the afternoon, we had thirty minutes allotted to listen to Maharishi Gandharva Veda, which Maharishi said would raise our IQs just by the sound of a CD of his trademarked sitar and tabla music. We started taking Gandharva Vedic music classes once a week. I plucked away halfheartedly at a sitar with an old Indian man who spoke almost no English and seemed vaguely contemptuous both of us and of rural Iowa. Sanskrit, first introduced during our SCI classes as a way to get closer to the Ved, would become a language requirement. In science, we’d learn about how Maharishi’s principles were clearly illustrated even in the process of photosynthesis—Life Is Found in Layers, Inner Depends on Outer.

Our school play that year was also based on Maharishi’s principles. Each elementary school kid would shout one of these principles after acting out one aspect of nature’s perfection. The kids in overalls, dressed as farmers, plowed the “Field of All Possibilities,” because as Maharishi said, “The Field of All Possibilities Is the Source of All Solutions.” I was assigned the role of a Southern belle, and was part of a group of about eight girls who waltzed across the stage, wearing gingham dresses and singing in a high falsetto about the wonders of such a perfectly functioning world. “How do the waves know when to wash to the shore,” we sang along, making a feminine little frame around our faces as instructed. “Oh what a bright, bright, intelligent world we live in!”

Positivity was paramount at the Maharishi School. We were told to always focus on the blissful aspect of life, and avoid negativity. One day, Mom got a call from one of Stacey’s teachers, reporting that he had been drawing monsters in art class. Monsters were not part of Bliss Consciousness. They suggested maybe Stacey might be un-stressing and needed some guidance. Mom pushed back—there were few areas that held higher ground for her than Maharishi’s Knowledge, and art was one of them. Stacey had been drawing monsters for as long as I could remember and Mom encouraged him as he developed them as googly-eyed, long-finger-nailed characters.

“Keep drawing the monsters, Stacey,” she told him. “But maybe just draw them at home.”

Copyright © 2016 by Claire Hoffman. Reprinted by permission of Harper, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.