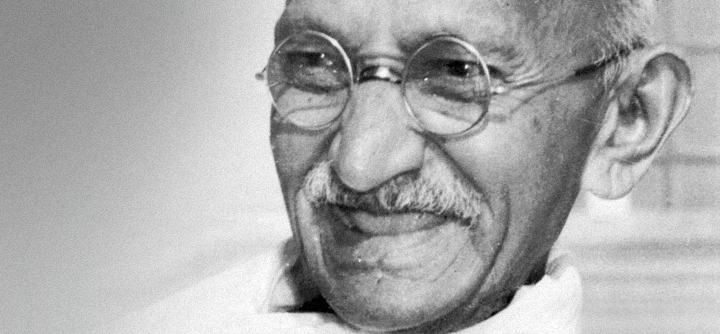

Gandhi. {PD}

The Mahatma reached over, his legs crossed before him on the floor. He grasped my hand firmly like any good Tammany politician. “You’d better sit over there,” he said, motioning to a varnished box about half the size of an orange crate six feet directly in front of him. This box was the only article of furniture in the room.

As an American advertising man travelling with press credentials Mahatma Gandhi had granted me an interview. Mr. Mahadev Desai, for twenty years his secretary told me it was the first interview this year given any writer or press representative. The Mahatma is partial to Americans. He cannot get a direct hearing in the English press; his only chance to reach the English is at rare intervals through America. He once called Americans brothers.

It was March 9 in Segaon, a thatch roofed Indian village of 75 or 100 mud houses. Most of Sagaon’s 500 inhabitants are untouchables. They are of India’s depressed class, those Mahatma calls “Harijan” or “Man of God.”

You reach Sagaon by train from Delhi—after 26 hours. I had arrived the evening before at hotel-less Wardha, the nearest railroad station and five miles distant. After a sleepless mosquito-ridden night on a bench in the station, I had hired a tonga or two-wheeled cart, Wardha’s only means of conveyance, and had driven across a plain as flat and scorching as Kansas at its worst to the Mahatma’s ashram.

Ashram, a famous word in Hindustani, means the resting place or hermitage of the holy man. To the ashram come seekers after guidance and knowledge. To the Mahatma’s, India’s political leaders currently stream in pilgrimage.

Gandhiji—the “ji” is a mark of respect—received me in his mud plaster one story bungalow. Hut would he a more accurate name for it. A small room is tacked onto a main room perhaps 15x25 feet in size. Three crude bamboo grills no larger than small napkins serve as windows. Light filters through the doors at front and back. A covered porch runs all the way around.

The porch is as confused and littered as the room of a boarding school girl the night before Christmas vacation. Seven oil hand lamps stand in one corner; the kind the North Dakota farmer carries to the barn on a winter’s night. A wooden pallet is shoved against one wall. Two cloth covered lattice cots and three bedding rolls sprawl nearby. Three tin suitcases lie under the cots. A wooden White Label case, empty of whiskey and stuffed with paper, incongruously nudges a modern bathroom scale.

These are the only objects to mark the twentieth century.

Five pairs of bedraggled slippers lie in confusion where they have been kicked off near the door. I had bought a pair not so dissimilar for one rupee (36 cents). These and the suitcases, l later discovered, belonged to a labor delegation that had been in attendance and consultation for three days. Those who enter the ashram go shoeless, as does the true believer into the Mosque.

Thirty feet to the rear of the Mahatma’s hut is another, about half as large with two closet sized rooms opening on a narrow porch. There a six year old, Gandhi’s grandson, stands and bawls for ten minutes, refusing to be comforted by a black bearded Indian who stops his work to kneel before the boy. This hut is a separate home for Mrs. Gandhi, mother of four sons. The Mahatma once advocated abstinence to Mrs. Margaret Sanger as the only acceptable method of birth control.

His eldest son, a middle aged man, is a turncoat Hindu; a few months ago he switched to Mohammedanism, then back to Hinduism again. He likes the softer, better things of life. He is not the son of the father. The other three sons are sympathetic with the Mahatma’s movement hut do not seem to be actively of it. Little is heard of them in India.

Further on to the rear, behind Mrs. Gandhi’s hut, is a third dun colored structure, about twice the size of a double bed. Here lives Miss Madeleine Slade. The daughter of an English admiral, Miss Slade for fifteen years has been a follower of Gandhi. Potent today in the movement to improve the lot of the Indian ryot or village farmer, she is perhaps second only to the Mahatma as a leader of Indian woman of all races and creeds.

On the near side of Miss Slade’s cabin two spinning wheels are moulded cameo-like on the mud wall. The spinning wheel is a symbol of Gandhi’s work. It appears on the flag of the Congress party, Gandhi’s nationalist political organization which has just won an overwhelming victory in the first election under the new constitution.

[[{"type":"media","view_mode":"media_original","fid":"1358","attributes":{"alt":"","class":"media-image","height":"347","typeof":"foaf:Image","width":"460"}}]]

Gandhi and Miss Slade in 1932. {PD}

Across the yard in front is the stable, the center of efforts to carry forward what Gandhi has called “one of the most wonderful phenomena in human evolution”—Cow Protection. This stable is covered with matting md open on the side towards the house. From it comes he droning sing song voice of an old woman chanting as she strokes and covers with mud a sick two weeks’ old calf.

Behind the group of cabins are three privies of bamboo matting. Such are new to Indian village life; sanitation is one of the platform planks in the movement for Village Uplift.

A few shreds of grass poke up here and there in the yard. Half a dozen waist high trees surrounded by bamboo wickets to keep goats at their distance, struggle toward the sun. Around the yard and mud huts, enclosing perhaps an acre, runs a three foot picket fence.

In this crude and primitive setting in the heart of India Gandhi has lived for a year past. Here may he live for years to come. To plumberless Wardha the Working Committee of the Congress Party migrates for crucial meetings. Here Gandhi maintains his spiritual overlordship while he delegates active political leadership to others.

Today he is avoiding the direct spotlight, gathering strength in repose for his next rhythmic attack on the English raj. Yet his hold on politicians remains as strong as ever. His magnetic power over the masses is undimmed. His closest associates do not know his next move. All agree, however, that where he leads tens of millions of Indians follow. Politician and purdah woman alike are swept in his train like bubbles in the wake of a ship.

As I settle myself on my box, I notice that the Mahatma’s knee length dhoti, usually his only article of apparel, is supplemented by a white head bandage fastened in front by a single safety pin worn with the Maharajah’s pride in an egg sized ruby.

Gandhi’s secretary later told me that this turban contains ordinary dirt, carefully sifted through a clean white cloth and kept well moistened. This treatment, plus garlic, avers Mr. Mahadev, has brought the Mahatma’s high blood pressure of a year ago down to normal. The secretary credits the cure to a German doctor, a Dr. Jost, and assures me that mother earth has remedial powers unrecognized by Western science.

Gandhi’s entire wardrobe consists of but two of these eighteen inch long homespun dhotis. Total cost, about one rupee. The orthodox Indian dhoti is ankle length. And how Gandhi’s became abbreviated is a characteristic story.

The Mahatma advocates cleanliness to India’s poor—the three hundred million whose average income is only 3 or 4 cents a day. Some fifteen years ago he was asked, “Mahatma, with but one dhoti to my name, how can I keep it clean?” Gandhi, always on the alert to identify himself with the poor, resolved to be no better off than the humblest of India’s peasants. He has confined himself to but one ankle length dhoti since. But from this customary long dhoti he makes two short ones. Thus one can always be clean.

The Mahatma’s eyes flash and subside behind his spectacles as he waits for me to begin. I hesitate. He gives me no lead or encouragement. He sits cross legged on the floor in a narrow recess formed on two sides by a corner of the room and on the third by a shoulder high pile of books and boxes. Shadowy light drifts through the doors and the small bamboo grills. There is showmanship in this recess and M. G. M. could not improve on the lighting. This is conscious staging, a simple illustration of Gandhi’s gift for the theatrical. Here the Mahatma benignly reigns like the idol in its wayside temple, gathering unto himself the traditions and powers of the five thousand year old Hindu Gods.

Scattered around the room, sitting on the floor with their backs against the wall, are the five labor delegates I have interrupted. In homespun coats and dhotis, they bore their black eyes like awls into my back.

I want to know the answer to the big issue in Indian politics today. Shall the victorious Congress party refuse to accept office, thus carrying passive resistance into the legislative halls? Or shall it accept office and bring in measures that the governors of the various provinces cannot sign?

[[{"type":"media","view_mode":"media_original","fid":"1362","attributes":{"alt":"","class":"media-image","height":"306","typeof":"foaf:Image","width":"460"}}]]

Nehru and Gandhi at the opening of the Indian National Congress in 1937. {PD}

The latter policy forces dissolution, and, over a period of time, is designed to “wreck” the new Constitution. Such a policy is exciting, dramatic, packed with the kind of thrill the Indian politician loves. The former policy, that of non-acceptance of office, is favored by Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, Gandhi’s ace lieutenant and the party president. Pandit Nehru is the firebrand of the party, the leader of India’s youth and the Mahatma’s political heir apparent. But Pandit Nehru may not be able to carry the party along with him.

The dilemma of the victor is a tough one. Many promises have been made at the polls. Many an Indian politician wants the rewards and prestige of office. The electorate may rebel at prolonged obstructionist tactics.

“This isn’t the time for such questions. I have work to do here. I can’t take myself from it to answer them,” he snaps a little testily, “You should ask these questions of the political leaders.” My surprised look at the Mahatma’s assumption that I would agree to exclude him from political leadership makes him add hurriedly, “Of course I wouldn’t say that I don’t know anything about politics. But I have no time for such questions now.” Gandhi’s pose today is that of the contemplative recluse. This is well keyed to Indian psychology. Although he cannot deny his leadership, in his public relations he does his best to sidestep admission of active political domination. Yet this is as real as it ever was.

Thus it is immediately made clear that on the eve of the Convention of the Congress party at Delhi, which the Mahatma is to attend, and at which, in theory, comes the showdown between the two schools of thought, I am to learn little from him of current political interest.

I try the Mahatma again. I ask whether there is any conceivable set of conditions under which the Congress party will accept office and try to make the new Constitution work. “That is a badly phrased question,” he replies, still sharply. Then he goes on, “Now if you’d asked me, ‘What is going to happen at Delhi?’ I’d say I don’t know. The issues are too confused, too complicated. Many feel that any form of cooperation is a mistake. Others disagree, feeling that perhaps our objectives can best be achieved by giving ground now and then. Both groups are sincere.” The Mahatma is ducking, sparring. He continues, “If we had lost and were in the minority, our course would be easy. I could tell you what the decision would be. I would know how to make it myself. But now I cannot tell. No man could know. The future must decide.”

Although the Mahatma will probably make the decision himself in the last analysis, and perhaps has already made it, he admits nothing. He continues, “We have just won a great victory and this brings us a big responsibility. I don’t know the election figures. I haven’t even read them. But I saw enough in the papers to know that our victory was overwhelming. We had literally no opposition. This is what counts. This result didn’t surprise me but it is a fine thing for others to see. It shows the world our strength.”

We talk then about American public opinion, its attitude towards India. “American opinion is of great importance to us,” admits the Mahatma, “and by our deeds we hope to win it.” I ask whether he is familiar with British propaganda methods in the States, the money and effort expended in America through the British Embassy and Consulates. Gandhi agrees that British foreign policy is often influenced by American opinion. He is aware that England tries in many devious ways to mould it. He remarks, “We cannot compete for American attention on the same terms with the English. We do not try. Our methods must be different methods. We make no conscious effort to influence American opinion. I believe that America is emotionally sympathetic with our cause, but it is profoundly ignorant of the real facts and of our real problem. When the time is right, America will learn the truth by what we do.” His voice trails off.

[[{"type":"media","view_mode":"media_original","fid":"1361","attributes":{"alt":"","class":"media-image","height":"347","typeof":"foaf:Image","width":"460"}}]]

Gandhi with textile workers in England on September 26, 1931. {PD}

“It’s a prevalent idea in America,” I comment, “that India requires England for defense. Without the English, would there be civil and religious disturbances? As the Congress party is successful in driving the English out of power in India, will India fall a prey to someone else? Or, for that matter, how will Congress deal with the native princes right here at home?”

“These are gross superstitions,” he replies, now at his gentlest and softest, “they have been propagated for years. Stories and statements of such dangers are hopelessly exaggerated. I know that many English people sincerely believe them; there you have the power of such ideas oft repeated.

“As to the native states,” he continues, “they’ll fall in line when India comes into her own.”

Little realized in America is the feudal and almost absolute power of some of these native rulers. They are feared and hated by Congress perhaps as much as the British.

I switch from politics. What does he think of the work of the American Missionaries in India? “I decline to answer that,” he shoots back abruptly. Well known is it that Gandhi has no regard for the missionaries’ plan of leading the 60,000,000 or 70,000,000 untouchables to the baptismal font of Christianity. “They would still be sweepers,” he once remarked.

A subject close to Gandhi’s heart, one on which he can and will talk freely: his great movement to improve the lot of the Indian villager or farmer who constitutes 85% of lndia’s total population. Two years ago he vigorously espoused the crusade of Village Uplift. In Wardha is the headquarters and plant of the Village Industries Association of which the Mahatma is both veins and arteries. There a school is run from which 130 have just been graduated after a year’s course. Out to the villages these 130 go as workers. At Wardha and at the ashram in Segaon, experiments are constantly being made, designed to develop new ways to improve the villager’s lot.

The platform of Village Uplift roughly divides into four major planks. First, handicrafts are developed to occupy the villager in the six months of the year when weather prevents his tilling his fields and when he has nothing to do. Chief among these handicrafts is spinning. Prior to the English rule, the villager spun his thread and wove his cloth. Now his few annas go to the cotton mills of Lancaster and Japan. Gandhi is reintroducing this lost native craft.

“See that boy there,” my volunteer guide told me as we visited Miss Slade’s cottage later in the day.

“He used to spend all his time spinning a top. Now be earns two annas a day spinning thread. Thus a man with four children has eight annas daily.”

An anna is 2 ¼ cents. The average wage for common day labor in Wardha, a city of 20,000 and further advanced than the villages, is 1 ½ or 2 annas daily.

The Village Industries Association bas developed papermaking, a crude wood pulp wetted down and dried in the sun. The villager is urged not to destroy the hive by fire and kill the wild bees for one comb of honey. He is shown how the bee can be domesticated.

Standard Oil and Royal Dutch Shell do not figure in Gandhi’s plan of village life. The blindfolded bullock goes round and round its large wooden mortar and pestle as oil is pressed from the thili seed for cooking, for bread, lamps, massage.

Experiments continue. The search is on for other handicrafts. The work is still very new.

The second major plank is the development of the native palm tree as a source of sugar. From an occasional palm alcoholic beverage is now distilled, as the Mexicans distill tequila from wild cactus. Millions of palms still await tapping for sugar.

I unwrapped a round hard lozenge looking in its paper much like the package of nickels the bank teller cracks on his till. Gingerly I bit. With zest I ate. The taste compares to good maple sugar, a rich sweet peanutty flavor.

India’s millions crave sweets and dumbly await instructions.

Third comes sanitation: a latrine of bamboo matting instead of the open field.

The fourth and perhaps the most important effort is “Cow Protection.” The cow is sacred to the Hindu and in general God is expected to look after his own. The peasant surely doesn’t. Cattle are abominably cared for. Many a cow is turned out to starve. In the plan for village uplift, the peasant is taught to tend, protect, and develop his cows.

Further, and at first blush paradoxically, comes care after death. Connected with the Wardha school is a tannery. Here no cattle are slaughtered. This would violate the Hindu faith. But after natural death, the carcass is skinned; the hide is tanned in a series of chemical baths made from chopped up bark, from lime, etc. I saw twenty women chopping bark at two annas pay per diem. The tanner tries to emulate Mr. Swift and Mr. Armour in utilizing every part of the carcass except the moo.

“Progress is slow,” the Mahatma tells me, “but you must remember that our work is new. We started with nothing but faith. Only faith. Today knowledge is added.”

He breaks into his well-known toothless smile, “You might add a third ingredient—give us part of the money you make when you sell your story!” he suggests. The Mahatma is famed for his humor. This was the first glimpse I’d had of it. “You think if faith plus knowledge are potent,” I reply, “faith plus knowledge plus capital are more so.”

“Yes, yes,” he cackles and rocks in a full laugh.

“Have you ever seen an American movie or heard American jazz?” I ask abruptly. “These are our two most famous exports.” I do not ask about American dentistry, perhaps third in fame. If he has heard of that he heard too late. He has been toothless almost as long as photographers can remember. And he again identifies himself with the poor by using no dental plate. Thus his words are often somewhat mumbled, blurred.

“No, no, I haven’t,” he laughs again, “there’s a good story for you. Do what you can with it.” The Mahatma realizes he has given me little political news. “I’ve never been to a moving picture,” he adds. “Hasn’t one ever been brought to you?” I query. “No,” he laughs again, “I have never seen one.”

My question is not asked in jest.

In the talking moving picture, cheaply made and shown with low cost portable projectors, lies a method for greatly speeding up the reaching of India’s illiterate millions with the story of village uplift. If the British Government were alert to steal the Mahatma’s thunder, or were sincerely interested in the lot of the Indian peasant, it would put 5% of its Indian Army appropriation into such talking moving pictures. In a decade the results would be incalculable. For all of its faith, Gandhi’s movement has little capital. Few of the rich ride his bandwagon.

As I leave Gandhi, I unwittingly overstep. Webb Miller, head of the United Press in London, once told me of securing his autograph. The last twenty minutes of our conversation, after we foreswore politics, are so friendly and informal that I produce a sheet of paper made by the Association in Wardha that I had purchased for one anna. I ask the Mahatma if he will sign it. The first and only such request I have ever made. “No,” he smiles shyly and turns his head. Then he sees my paper. “No,” he giggles cheerfully, “even that does not tempt me.” Again we shake hands crisply.

[[{"type":"media","view_mode":"media_original","fid":"1359","attributes":{"alt":"","class":"media-image","height":"347","typeof":"foaf:Image","width":"460"}}]]

Gandhi laughing. {PD}

As our tonga meanders through its hour’s drive across the sun-blistered plain to Wardha, Mr. Mahadev tells me the Mahatma has given autographs only in London. And I think him right in refusing them. The autograph collector is a pest as unmitigated as the boll weevil.

“When I was in jail,” Mr. Mahadev begins a story. He has served six or seven years in jail, not far behind the Mahatma’s record. “They’ve been very considerate twice,” he tells me, “They know how close I’ve always been to Gandhiji and twice they’ve let me share the same cell with him, once for a year and a half.” As we plod homeward and trainward I try to picture the tens of thousands in India who speak of their years in jail with pride; these are the American Legion of Indian politics. And tens of millions more will cheerfully face jail, mutilation or death at a nod from the 69 year old politician-saint who makes of whatever village he occupies the most important town in India, and of whatever mud hut or room, one of the most important in today’s world.

[[{"type":"media","view_mode":"media_original","fid":"1363","attributes":{"alt":"","class":"media-image","height":"360","typeof":"foaf:Image","width":"460"}}]]

Benton. (Photography by Austen Field/University of Chicago Photographic Archive, apf1-00561, Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library)

William Benton (1900–1973) was an advertising executive, publisher, University of Chicago administrator, US senator, and diplomat. When asked about the rare interview, Benton admitted it was a challenge. Gandhi lived “among peasants at Segoan, five miles from Wardha and there is no hotel anywhere near,” he said. “I was pretty keen on interviewing him so I just had to sleep in the railway waiting room for the night. But it was well worth it. Meeting a man like that is a great experience.”

Reprinted in the Magazine

by special permission of the North America Newspaper Alliance.