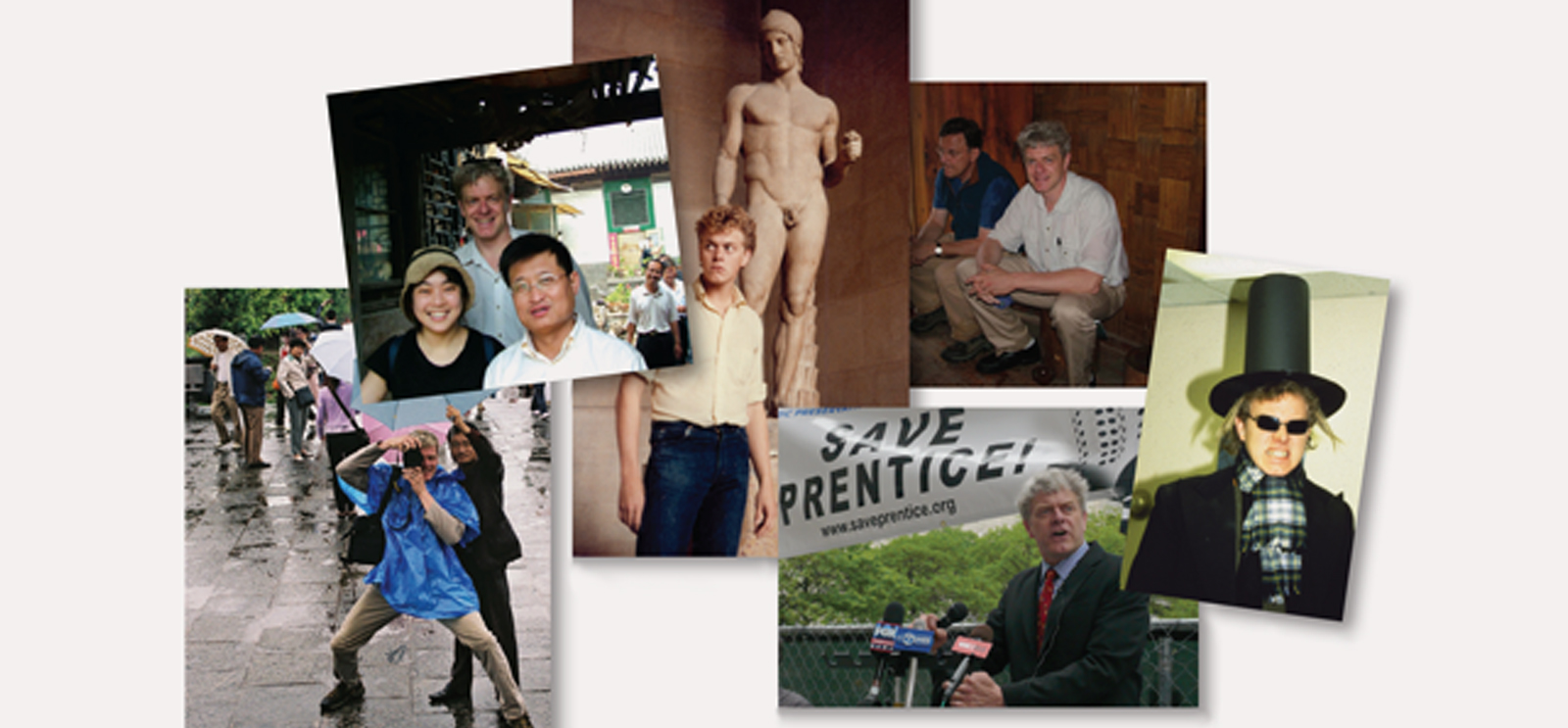

(Clockwise from top center) On a 1982 backpacking trip through Europe, Michael visited the Louvre; Michael sits with Jerry Adelmann at China’s Gaoli Gong Shan national park in 2008; in December 1989 Michael dressed as Scrooge while protesting Citicorp’s bid to buy and raze the Chicago Building; this past June, Michael announced that Northwestern’s old Prentice Women’s Hospital, planned for demolition, had made the National Trust’s list of 11 most endangered sites in America; in Dali City near Weishan in 2006, his student Colleen Rogers captured him in the rain; in 2008 Michael visited China’s ancient city of Pingyao, which the Global Heritage Fund is working to preserve. (Photos courtesy Vince Michael)

Vince Michael, AB’82, AM’82, builds community by saving buildings.

In December 1989 Vince Michael picketed Citicorp’s downtown Chicago headquarters, dressed as Santa Claus one week and Scrooge the next. Michael, AB’82, AM’82, and fellow activists at the Landmarks Preservation Council of Illinois were protesting the bank’s $15 million bid to buy the early-1900s Chicago Building, at State and Madison Streets, and raze it. Michael in costume made for a photo opportunity, and the image made the Chicago Sun-Times, along with ongoing coverage there and in the Tribune. Within a few months, Citicorp bowed out, and the Chicago Building now serves as a dormitory for 200 students at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Saving the building, Michael says more than 20 years later, was the “big triumph in my career.” Named the John H. Bryan chair in historic preservation at the School of the Art Institute in 2006, the same year he became a trustee of the National Trust for Historic Preservation, he has spent that career waging campaigns, advising neighborhood residents and policy makers, and teaching about preservation in Illinois; Palm Springs, California; Ireland; and China.

Before all that, Michael studied history in the College. He took courses with John Hope Franklin, the African American scholar who helped to weave the story of black people into mainstream US history, and with Kathleen Conzen, an expert on German immigration and American urban history. Conzen once told Michael’s class that when she walked into the 1882 Turner Hall in Milwaukee, designed by German immigrant Henry C. Koch and named for the pro-labor German-American society, she could hear the voices of long-dead heroes of her research. It was an “if-these-walls-could-talk” moment, Michael says.

Hyde Park, where the Gothic quadrangles not only organize the University’s real estate but also evoke its spirit, fed his interest in history and buildings. Yet nearby loomed the influence of urban renewal. “Living in Hyde Park,” he says, “I was acutely aware that old 55th Street had been urban renewaled out of existence.” Writing for the Grey City Journal, he and other students debated with architects “who were defending this stuff.” The neighborhood, he says, is a “good example of top-down redesigned urban planning from the ’50s.”

In 1983 Michael got his first preservation job, “a Reagan-era limited-government approach to preservation,” he says. Working for the Upper Illinois Valley Association (now the Canal Corridor Association), he helped to establish the Illinois and Michigan Canal National Heritage Corridor. The association’s director, Jerry Adelmann, hoped recognizing the canal’s history, which reaches back to 1848, would promote economic development in towns along its banks.

While at the association Michael worked with Gaylord Donnelley, the late head of R. R. Donnelley and Sons (and a former University trustee), to restore a stone warehouse Donnelley’s forebears had owned in Lockport, Illinois. Now called the Gaylord Building, it houses cultural attractions and a destination restaurant that has helped the town draw other high-end eateries. The association also helped to revive other distressed towns and to restore a mansion designed by William Boyington, the architect of Chicago’s Water Tower, and a Civil War–era grain silo in Seneca, Illinois.

Still, the main lesson Michael learned from that job, after working with Rotary clubs and chambers of commerce from Cook County to LaSalle-Peru, was that “support for preservation is a mile wide and an inch deep.” People agreed that using history to improve their towns was a good idea; getting money to do so was another matter.

Throughout the 1980s, preservation took on a higher profile, partly because of building booms encouraged by real-estate tax credits. In 1986 Michael joined the Landmarks Preservation Council of Illinois (now Landmarks Illinois) as Chicago programs director. Leading the Chicago Building campaign a year later, he also soon got his first close view of “the democracy of the built environment,” as he describes community members advocating for their neighborhoods.

Residents in North Kenwood, near Hyde Park, had been arguing with professional preservationists at the city’s Commission on Chicago Landmarks. The commission had proposed saving two small blocks as historic districts within North Kenwood and neighboring Oakland. The community activists, Michael writes in a 2005 Future Anterior article, were “tired of two decades of planning policy limited to the demolition of old homes and construction of large amounts of subsidized housing of dissonant character.” They wanted to save their old graystones, some of which the city had declared “blighted,” and asked Michael to help. The professional preservationists had approached the project from an architectural-history perspective, looking at significant buildings, but the residents did their own research to identify important early residents of the neighborhood, such as Civil War hero General Charles Bantley and Gottfried Brewery Company owner Matthew Gottfried.

In August 1991 the commission proposed creating a “multiple resource district,” which would allow other agencies to build new housing while also protecting 173 properties in North Kenwood and Oakland. The community members liked the approach but wanted even more properties protected. After several rounds of negotiations, with Michael serving as arbiter, in early 1993 the activists succeeded in growing the district to 338 properties. After the designation, Michael writes in the journal article, “North Kenwood saw a spate of rehabilitation and new construction projects” designed to complement existing homes. The episode was a rare case where “the community rose up,” he writes, “and dragged the professionals along with them.”

Such practical experience proved useful when he applied for a teaching position in the School of the Art Institute’s historic-preservation program in 1996. Arguing that unlike many of the artists on the faculty, he had the administrative and managerial skills “to be able to run the program as opposed to just teaching it,” he got the job. “I was on the slowest tenure track possible because I didn’t have a strong teaching background,” he says. “I taught one course there for two years.”

Finding himself in academia, Michael sought a doctoral degree. He studied at the University of Illinois at Chicago under architectural historian Bob Bruegmann, using his North Kenwood experience in a 2007 dissertation about historic districts in New York and Chicago.

He’s taken his expertise far beyond Chicago, working since 2004 with the US-China Arts Exchange, which is developing a medieval town, Weishan, on China’s Southern Silk Road. The goal, he writes on his blog, Time Tells, “is to conserve historic buildings and landscapes and intangible heritage to serve both tourism development and the local community.” He and students have helped to preserve landmarks such as the 1390 North Gate in the old city, which “is now being used for community events and music as well as serving as a tourist destination.”

It’s a project that reflects his preference for the term “heritage conservation” over something like “historic preservation,” which in the past has focused mostly on buildings and architecture. “So much of what we do—and certainly the stuff we do in China, the stuff I did in my dissertation—it’s all about conserving community.”