From our print archive: Our atomic leadership may be only temporary.

With the dropping of the two atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the consequent collapse of Japanese resistance, there was elation and even joy in our accomplishment, but as the days pass it is becoming evident that the peoples of the world, and particularly we Americans, are beginning to recognize that this accomplishment raises problems of peace that will be at least as great as those of war. The atomic bomb has opened Pandora’s box and instead of returning to the good old days, as we had hoped, we shall be forced to live in a period of anxiety and fear.

We had expected to insure peace for many years by controlling the enemy and insisting that he change his ways of life and his political philosophy; the atomic bomb now asks us to change ours. And that is not going to be easy to do. In this sense we have been conquered by the atomic bomb. Every solution to the problem of peace now seems to end in a dilemma, unless we, the American people, are willing to change our thinking about international affairs. If only to protect ourselves, we must give as much, and even more, than we receive; the prevention of war must be more important to us than any possible national interest; national sovereignty must play a secondary role. The problem now is, not one of preparation, but of prevention of war by any and every means and at whatever cost.

[[{"type":"media","view_mode":"media_original","fid":"1810","attributes":{"alt":"","class":"media-image","height":"285","typeof":"foaf:Image","width":"460"}}]]

Aerial photographs of Hiroshima’s Aioi Bridge before (left) and after the atomic bomb was dropped. {PD}

When it became apparent that the war in the European theater was fast coming to a close and when the scientists and engineers on the atomic bomb project also realized that the atomic bomb had a good chance of coming through before the Japanese were defeated, men with greater imaginations realized what its impact on the world would be; they realized that in the not too distant future all of civilization could be destroyed. In private deliberations they considered the various courses of action the government could follow, and even made recommendations to higher authorities, none of the participants of these debates having any word in the final decision to be adopted. These proposals ran all the way from not dropping the bomb at all, and thus hoping to preserve the secret completely, to dropping the first bomb into the heart of Tokyo. The emphasis on humanitarian motives was consistently avoided, and an attempt was made to consider only world stabilization and peace.

It was argued that if the bomb were not dropped, even experimentally, nobody would know whether it would be successful, and the assumption could be made that the venture was a failure and would therefore not be tried by other countries. Furthermore, the war could be won without it. The arguments against such a procedure were that the secret, as far as it went, could not be kept, that there was an expenditure of two billions of dollars to be accounted for, that to get government funds for further work in this field it was necessary, in a democracy, to get the approval and support of the people, and that such a course might cost many American lives. This seemed to be an impractical solution although it was advocated by some of the scientists on the atomic bomb project.

In compromise it was suggested that an experimental bomb be exploded in the presence of invited Japanese high officials; the damage that such a bomb would do to a Japanese city could be interpreted from the visual effects and from the automatic recording of gauges. But the negotiations necessary for such a procedure would be so drawn out that the war would be over before it was accomplished. Furthermore, there was the fear that such a demonstration would not convince the American people of the danger ahead. It was also suggested that some isolated spot such as Truk be selected as the target, but again a bomb dropped on such a target would not sufficiently influence the Japanese or the American people. Finally it was proposed that a target be selected which was of importance to the Japanese war effort and the bombing of which, while demonstrating the effectiveness of the bomb, would kill as few civilians as possible. A second bomb might be necessary to demonstrate to the enemy that more were on hand If they did not capitulate.

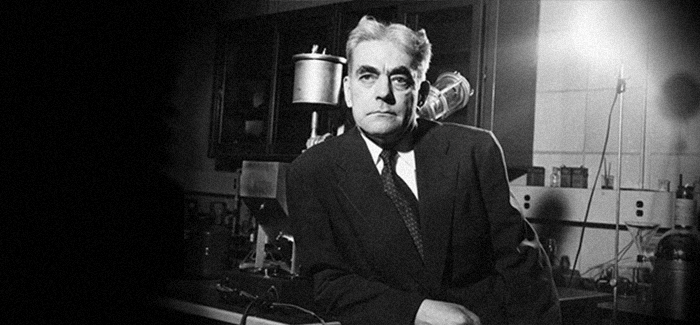

[[{"type":"media","view_mode":"media_original","fid":"1808","attributes":{"alt":"","class":"media-image","height":"374","typeof":"foaf:Image","width":"460"}}]]

Thorfin R. Hogness. (University of Chicago Photographic Archive, apf1-02850, Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library)

We may be sure that these arguments with many variations were considered by the highest officials of our government for several months preceding the Hiroshima bombing, and we have been indirectly informed that it was with the greatest reluctance that the American government chose the course that it did. Rightly or wrongly, Hiroshima and Nagasaki were atom-bombed and the great secret was out. The bomb works.

In one respect the decision of our government has led to a successful conclusion. The war ended abruptly, and, we hope, saved more Japanese as well as more American lives than it cost. In its other respect, that of demonstrating its awfulness to the extent that it will prevent future war, it seems doubtful that it will succeed.

It is a common assumption that the present atomic bomb is the ultimate in destruction. If one of these present models should explode over Manhattan it would do a great deal of damage, but it would not put all of New York out of action, for there is a great deal of architectural difference between New York and Hiroshima. But it must be borne in mind that the Hiroshima bomb is only a baby as compared with what might be developed in the future.

In the beginning of this war the Americans, as well as the Germans, considered an ordinary 1,000-pounder a big bomb, but toward the end of the war 20,000-pounders had been developed. In terms of TNT as a standard of comparison, the atomic bomb is at least a 40,000,000-pounder. As the TNT bomb developed 20-fold during this war so in the next war we might expect 1,000,000,000-pounders and only one of these would completely obliterate even New York or London. But these new models are not going to come to us by merely passing secrecy laws and rubbing an Aladdin’s lamp. Nor are they in the immediate offing, ready for the technologist and the production engineer. The super-bomb may perhaps be only around the corner, but much conjecture, interchange of ideas and experimentation would be necessary before it could be realized.

Barely three months have elapsed since the world at large first heard of the atomic bomb and already Congress is about to enact legislation that will affect our future course of action, a course which, because of our unique position as owners of the bomb, will affect our international relations and the security of peace for years to come—or until the next war. By precipitous action we may be spelling our own destruction. From everywhere we hear “Let us keep the secret to ourselves and thus secure our own position.” Let us analyze this assumption that secrecy means security.

The history of military weapons has been that for every new offensive weapon a defensive measure has always been found; thus, the coat of mail against the lance and the arrow, the tank against the bullet, and the jamming devices against radar. But in all of these advances in measures and counter-measures the advantage of the offensive weapon at any one time was only a matter of one- or two-fold increase in efficiency of destruction. The atomic bomb, on the other hand, has placed the offensive in such a strong position that there is no counter-measure in sight and the surprise element is now completely realizable. In the past, the surprise element in attack, always sought, could be accomplished only through scheming and subterfuge, but now the atomic bomb, contained in a guided missile or planted as a landmine, could completely change this situation. In the future, it will be possible for any country having enough super-bombs to completely destroy another in an hour’s time. The atomic bomb presents destructive power beyond human imagination, as well as the element of complete surprise.

With no counter-measure against such a ghastly possibility the American people in desperation and ignorance have been driven to the only defensive measure apparently at hand—keeping the secret of the atomic bomb to ourselves.

[[{"type":"media","view_mode":"media_original","fid":"1809","attributes":{"alt":"","class":"media-image","height":"323","typeof":"foaf:Image","width":"460"}}]]

Hiroshima aftermath. (CC-PD-Mark)

It has been repeatedly stated that there is no secret to be kept, but to a social scientist, an economist, a lawyer, a statesman, a lawmaker, to the layman, that statement does not make sense because the secret was so well kept during the war period. Why cannot that state of affairs be continued after the war?

The greatest of all the atomic bomb secrets has already been divulged—the bomb is successful. Had the German government had faith in their scientists, rather than in Blitz warfare, and any fear that their enemy might develop an atomic bomb before the end of the war, then the German effort might have been a hundred-fold greater than it was. After Hiroshima, every power on earth knows that it can be done and must be done. The job is not too difficult, even beginning from scratch. The road to be followed is outlined in the Smyth report.

Most of the remaining secrets lie in a certain amount of “know how” and in a high degree of industrial development, and it is in this respect that other countries lag behind us. We could give any other country the basic scientific information on atomic fission which we now possess and it is conceivable that by so doing their date of delivery of their bomb would not be shortened one day because their bottleneck will be industrial facility and technical expertness. By withholding this basic scientific information we shall force other countries to inaugurate such extensive research programs that they may easily surpass us in a relatively few years. Since our own scientific advance demands free exchange of information and ideas we cannot lose by releasing pure scientific information. Also, it must not be forgotten that the basic information obtained before the war that made our atomic bomb possible was discovered by foreign scientists and some of these men contributed vitally to our present accomplishment. We are not as superior as we think we are.

While it may be advisable not to disclose some of the technical information that is of pure military value, such as the detonating mechanism of the bomb, yet most scientists believe that the government, while being kept fully informed, should exercise no control at all over purely scientific work. In fact, they feel sure that they cannot produce good scientific work under conditions such as those imposed by the exigencies of war. This does not mean that the government should not have any control whatsoever over scientists. Research work in the field of nucleonics may offer potential hazards to the neighboring community and the community therefore must be safe-guarded by law. But what the scientist discusses and writes with regard to pure science cannot be restricted by any non-scientific agency if progress is to be made.

Most people do not realize that the “scientific” work carried out during war was, for the most part, technology, that the scientists became technicians, only making practical applications of the science and knowledge gained in the past by free scientists who were allowed to discuss their hunches, their ideas, deductions, and conclusions with each other. Nor is it possible to foresee which of these ideas will lead directly or indirectly to the more practical aspects of the problems of nuclear fission.

A relatively few years ago Einstein deduced his theory of relativity which brought forth such concepts, often ludicrous to the popular mind, as: a moving ruler is shorter than a stationary one; and a moving clock ticks slower than it would if it stood still. Weird geometries were resorted to, to explain these new concepts, and Einstein’s ideas—even Einstein himself was by many people considered “phoney”—just a long-haired professor. But out of this theory came the deduction that mass and energy were equivalent through the equation: energy equals mass times the square of the velocity of light. This relationship said that whenever heat or energy was given out by any mass, that mass lost weight in accordance with the above equation. It was through the theory of relativity that scientists were able to deduce that the fission process released such enormous quantities of energy and this deduction eventually led to the production of the atomic bomb.

Again, Bohr and Wheeler, in a paper on the structure of the nucleus suggested that those heavy nuclei that had even atomic numbers and odd mass numbers were fissionable. Thus uranium235, the fissionable component of natural uranium, has the even atomic number 92 and the odd mass number 235. It is very doubtful that experiments to determine the fissionability of plutonium239 would have been tried early enough to make plutonium a vital factor in this last war unless Bohr and Wheeler had suggested the probability of their being successful. Little did either Einstein or Bohr and Wheeler realize at the time of their postulates and deductions that they would contribute so significantly to the closing of the greatest war of all time.

The scientific “nonsense” of today often becomes the hard reality of tomorrow. The idea that free exchange of scientific knowledge can be the means of safety may seem nonsense to the laymen of today, but tomorrow it may very probably prove the means of preventing a most horrible war.

Now what is our government proposing to do to foster science and to preserve our scientific and technological advantage in the field of nucleonics? In his message to Congress, President Truman made a statement permeated with idealistic sentiment for the security of the nation and for the welfare of humanity at large and proceeded to implement those ideals by introducing through Senator Johnson and Representative May a bill on the control of the atomic bomb and nuclear energy.

This bill provides for the establishing of a commission of nine men to be appointed by the President which in turn will appoint an administrator and deputy administrator. Special provisions are made to allow for the appointment of an army, a navy or a government officer as administrator and as deputy administrator. Furthermore, the administrator will be required to keep the deputy administrator informed on all subjects under his jurisdiction, a relationship that now exists between the army and navy members of our general staff. The way is open for military control should the President so choose.

“The commission shall have plenary supervision and control—over all matters connected with research on the transmutation of atomic species, the production of nuclear fission and the release of atomic energy.” The commission is authorized and directed to establish and provide for the administration of security regulations governing all knowledge and research in this field. The commission, through the administrator, can not only control scientific work but is directed to set up an espionage system against the scientists who are expected to do the work, and through very heavy penalties the research workers are expected to be kept in peonage.

Any violation of any regulation promulgated by the commission shall be grounds for dismissal from employment, even by licensees of the commission, “without regard to criminal prosecution or conviction thereunder” and any violation of any regulation, regardless of intent, shall be punishable by a fine of not more than $500 or by imprisonment of not more than 30 days. But if this violation is willful or is committed through gross negligence the fine is not more than $100,000 and the imprisonment not more than 10 years, or both. No inducement, but rather punishment, is offered for scientific discovery. It is hard to believe that any scientist was consulted in the framing of this bill.

The bill contains a statement to the effect that the commission shall interfere as little as possible with research conducted by non-profit institutions and the scientists will be told that it is not the intent of the government to stifle scientific research and that they should have faith in the administrators in Washington. But with the far-reaching powers of the commission for dismissal and severe penalty, can scientists feel free to discuss their scientific work even among themselves; can they lecture on the subject of their research and train the necessary new scientists; can scientific directors afford to be lenient in the matters under their jurisdiction, without becoming accessories; can the army or those entrusted with security afford to be liberal; and will scientists put their necks into such a noose? But the most important question of all is: Can American science advance and flourish under these conditions even under the most lenient administration? The primary principle leading to big scientific advance lies in the freedom of the scientist to follow and discuss his inspirations and the demand for this freedom arises out of practical necessity.

The hope of every nuclear scientist, as of every good citizen of this world, is that the atomic bomb will force all nations into an accord and make for a lasting peace. The hope is a more fervent one, if this is possible, for the scientist, for we have been projected into this crisis as a result of his work. Can we bring about international accord by keeping scientific facts secret, temporarily assuming the leading position through fear, and aggravating those with whom we must eventually come to a common understanding? We now have a herrenvolk complex just as Hitler and his gang had and this feeling will grow until we have alienated our friends and allies to an extent that restoration of confidence will be difficult or until it is too late. The first step should be that of releasing the basic nuclear scientific information we possess. Through science, which has always been international, we can make our initial gesture of good will, thereby contributing to the security of future generations of Americans.

The only defense against the atomic bomb is not secrecy but the creation of international good will and faithful agreement that there shall be no more wars. We who now own the bomb must take the lead.

Thorfin R. Hogness, (1894–1976) was a University of Chicago physical chemistry professor (1930-1959) and director of the Metallurgical Laboratory’s chemistry division (1944–1945). Hogness also served as the director of UChicago’s Institute of Radiobiology and Biophysics and was on the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists’ Board of Sponsors.